10 Surprising Facts to Know Before Reading the Qur’an

This article presents ten little-known all-important facts about the Holy Qur’an (the scripture of Islam), which both Muslims and non-Muslims remain generally unaware of. For those who remain skeptical about the historical existence of Prophet Muhammad and the dating/transmission of the Qur’anic Text, we first present historical evidence that Prophet Muhammad lived and preached in Arabia in the first half of the seventh century and then show manuscript evidence and academic scholarship that shows the present day Qur’anic Text dates from around 650 CE. Following this, we present ten all-important facts about the Qur’an that have been uncovered by historical scholarship, which change the way one approaches and reads the scripture of Islam.

A. How Do We Know Prophet Muhammad Actually Existed?

Muhammad is not completely a fiction of later pious imagination, as some have implied; we know that someone named Muhammad did exist, and that he led some kind of movement. And this fact, in turn, gives us greater confidence that further information in the massive body of traditional Muslim materials may also be rooted in historical fact.

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam, 53)

While it has become popular to question the very existence of Prophet Muhammad and other major religious figures like Moses, Jesus, and Buddha, the historical evidence for Prophet Muhammad existing and living in 7th century Arabia is vast and well documented. Several examples of the earliest sources documenting the existence and mission of Prophet Muhammad are summarized below:

1. A Byzantine Greek text called Doctrina Iacoba (Jacoba) dated by scholars by to July 634 – written within 2 years of Muhammad’s death – confirms that an Arab Prophet existed and claimed to have the keys to paradise:

There is no doubt that Mohammed existed, occasional attempts to deny it notwithstanding. His neighbours in Byzantine Syria got to hear of him within two years of his death at the latest; a GREEK TEXT written during the Arab invasion of Syria between 632 and 634 MENTIONS that “a false prophet has appeared among the Saracens” and dismisses him as an impostor on the ground that prophets do not come “with sword and chariot”. It thus conveys the impression that he was actually leading the invasions…If such a revised date is accurate, the evidence of the Greek text would mean that Mohammed is the only founder of a world religion who is attested in a contemporary source. But in any case, this source gives us pretty irrefutable evidence that he was a historical figure.

Patricia Crone (Former Professor of Oriental Studies – University of Cambridge), (“What Do We Actually Know About Mohammed”, June 2008, Read Here)

2. A Syrian manuscript folio examined by W. Wright which dates to 636 AD (4 years after Muhammad died) mentions Muhammad and the Arab conquest of Syria. Documented in W. Wright, Catalogue Of Syriac Manuscripts In The British Museum Acquired Since The Year 1838, 1870, Part I, Printed by order of the Trustees: London, No. XCIV, pp. 65-66. More details here.

3. Another Syrian manuscript mentions Muhammad and the Arab conquests and this also comes from the year 634 AD – 2 years after Muhammad died. See W. Wright, Catalogue Of Syriac Manuscripts In The British Museum Acquired Since The Year 1838, 1872, Part III, Printed by order of the Trustees: London, No. DCCCCXIII, pp. 1040-1041. More details here.

4. The writing of the Syrian Christian Thomas the Presbyter in 640 testifies that Muhammad existed and led a movement. That is just 8 years after his death:

For example, an early Syriac source by the Christian writer Thomas the Presbyter, dated to around 640 – that is, just a few years after Muhammad’s death – provides the earliest mention of Muhammad and informs us that his followers made a raid around Gaza. This, at least, enables the HISTORIAN TO FEEL MORE CONFIDENT that Muhammad is not completely a fiction of later pious imagination, as some have implied; WE KNOW THAT SOMEONE NAMED MUHAMMAD DID EXIST, and that he LED some kind of MOVEMENT. And this FACT, in turn, gives us greater confidence that further information in the massive body of traditional Muslim materials may also be rooted in HISTORICAL FACT. The difficulty is in deciding what is, and what is not, factual.

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam, 53)

5. The Qur’an provides direct evidence of Muhammad. Not only does it mention Muhammad by name, but it mentions and describes Muhammad as a prophet and various events in his life and the life of his community. And the scholarly consensus is that the Qur’an as we have it today certainly contains what Muhammad said and recited in his lifetime:

Mohammed is also mentioned by name, and identified as a messenger of God, four times in the Qur’an… We can be reasonably sure that the Qur’an is a collection of utterances that he made in the belief that they had been revealed to him by God. The book may not preserve all the messages he claimed to have received, and he is not responsible for the arrangement in which we have them. They were collected after his death – how long after is controversial. But that he uttered all or most of them is difficult to doubt.

Patricia Crone (Former Professor of Oriental Studies – University of Cambridge), (“What Do We Actually Know About Mohammed”, June 2008, Read Here)

For example, meticulous study of the text by generations of scholars has failed to turn up any plausible hint of anachronistic references to important events in the life of the later community, which would almost certainly be there had the text crystallized later than the early seventh century C.E. Moreover, some of the Qur’an’s vocabulary suggests that the text, or significant parts of it, hailed from western Arabia. So we seem, after all, to be dealing with a Qur’an that is the product of the earliest stages in the life of the community in western Arabia…The fact that the Qur’an text dates to the earliest phase of the movement inaugurated by Muhammad means that the historian can use it.”

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam, 56)

6. The Constitution of Medina is preserved in 8th century sources and all scholars accept it as authentic and going back to Muhammad’s own lifetime when he ruled over Madinah (Yathrib):

On the Islamic side, sources dating from the mid-8th century onwards preserve a document drawn up between Mohammed and the inhabitants of Yathrib, which there are good reasons to accept as broadly authentic; Mohammed is also mentioned by name, and identified as a messenger of God, four times in the Qur’an.”

Patricia Crone (Former Professor of Oriental Studies – University of Cambridge), (“What Do We Actually Know About Mohammed”, June 2008, Read Here)

7. Other non-Muslim sources attesting to Muhammad include Christian and Persian writings:

a) Sebeos, Bishop of the Bagratunis (Writing in 660s CE / 40s AH)

Moreover, an Armenian document probably written shortly after 661 identifies him by name and gives a recognisable account of his monotheist preaching.

Patricia Crone (Former Professor of Oriental Studies – University of Cambridge), (“What Do We Actually Know About Mohammed”, June 2008, Read Here)

One of the most interesting accounts of the early seventh century comes from Sebeos who was a bishop of the House of Bagratunis. From this chronicle, there are indications that he lived through many of the events he relates. He maintains that the account of Arab conquests derives from the fugitives who had been eyewitnesses thereof. He concludes with Mu‘awiya’s ascendancy in the Arab civil war (656-61 CE), which suggests that he was writing soon after this date. Sebeos is the first non-Muslim author to present us with a theory for the rise of Islam that pays attention to what the Muslims themselves thought they were doing (see R. G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey And Evaluation Of Christian, Jewish And Zoroastrian Writings On Early Islam, 1997, op. cit., p. 128). He says the following about Prophet Muhammad:

At that time a certain man from along those same sons of Ismael, whose name was Mahmet [i.e., Muḥammad], a merchant, as if by God’s command appeared to them as a preacher [and] the path of truth. He taught them to recognize the God of Abraham, especially because he was learnt and informed in the history of Moses. Now because the command was from on high, at a single order they all came together in unity of religion. Abandoning their vain cults, they turned to the living God who had appeared to their father Abraham. So, Mahmet legislated for them: not to eat carrion, not to drink wine, not to speak falsely, and not to engage in fornication. He said: ‘With an oath God promised this land to Abraham and his seed after him forever. And he brought about as he promised during that time while he loved Ismael. But now you are the sons of Abraham and God is accomplishing his promise to Abraham and his seed for you. Love sincerely only the God of Abraham, and go and seize the land which God gave to your father Abraham. No one will be able to resist you in battle, because God is with you.”

Bishop Sebeos, (in R. W. Thomson with contributions from J. Howard-Johnson & T. Greenwood), The Armenian History Attributed To Sebeos Part – I: Translation and Notes, 1999, Translated Texts For Historians – Volume 31, Liverpool University Press, pp. 95-96)

Sebeos was writing the chronicle at a time when memories of sudden eruption of the Arabs was fresh. He knows Muhammad’s name and that he was a merchant by profession. He hints that his life was suddenly changed by a divinely inspired revelation (see R. W. Thomson with contributions from J. Howard-Johnson & T. Greenwood, The Armenian History Attributed To Sebeos Part – II: Historical Commentary, 1999, Translated Texts For Historians – Volume 31, Liverpool University Press, p. 238). He presents a good summary of Muhammad’s preaching, i.e., belief in one God, Abraham as a common ancestor of Jews and Arabs. He picks out some of the rules of behaviour imposed on the umma; the four prohibitions which are mentioned in the Qur’an. Much of what he says about the origins of Islam conforms to the Muslim tradition.

b) A Chronicler Of Khuzistan (Writing c. 660s CE / 40s AH)

This is an anonymous and short Nestorian chronicle that aims to convey church as well as secular histories from the death of Hormizd son of Khusrau to the end of the Persian kingdom. Because of its anonymity, it is known to scholars as the Khuzistan Chronicle, after its plausible geographical location or Anonymous Guidi, after the name of its first editor. Amid his entry on the reign of Yazdgird, the chronicler gives a brief account of the Muslim invasions:

Then God raised up against them the sons of Ishmael, [numerous] as the sand on the sea shore, whose leader (mdabbrānā) was Muḥammad (mḥmd). Neither walls nor gates, armour or shield, withstood them, and they gained control over the entire land of the Persians. Yazdgird sent against them countless troops, but the Arabs routed them all and even killed Rustam. Yazdgird shut himself up in the walls of Mahoze and finally escaped by flight. He reached the country of the Huzaye and Mrwnaye, where he ended his life. The Arabs gained control of Mahoze and all the territory.

Chronicler of Khuzistan, (R. G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey And Evaluation Of Christian, Jewish And Zoroastrian Writings On Early Islam, 1997, op. cit., p. 186)

B. Scholarly Findings on the Dating of the Qur’anic Text

Mohammed is also mentioned by name, and identified as a messenger of God, four times in the Qur’an… We can be reasonably sure that the Qur’an is a collection of utterances that he made in the belief that they had been revealed to him by God. The book may not preserve all the messages he claimed to have received, and he is not responsible for the arrangement in which we have them. They were collected after his death – how long after is controversial. But that he uttered all or most of them is difficult to doubt.

Patricia Crone (Former Professor of Oriental Studies – University of Cambridge), (“What Do We Actually Know About Mohammed”, June 2008, Read Here)

What is today called the Qur’an was originally a set of oral recitations uttered by Prophet Muhammad over 23 years in various times, places, contexts, and situations. It was common for Muhammad’s companions to memorize these recitations and write some of them down on rocks, leaves, parchment, etc. Prophet Muhammad never collected the Qur’anic recitations into a single document and never published the Qur’anic recitations as a “book.” According to Muslim sources, on the suggestion of Abu Bakr and ‘Umar, the scribe Zayd b. Thabit collected the verses of the Qur’an into a codex. Later, Zayd led the project to compile a standardized uniform version of the Qur’an Text under the supervision of Uthman (d. 656). In recent times it has become common for some Orientalist scholars to pen “conspiracy” theories – suggesting that the Qur’an was “invented” at much later date – 1 or 2 centuries after Muhammad’s lifetime (John Wansbrough); or that the Qur’an is merely a translation of some unknown, empirically inaccessible yet presumed Syrian Christian liturgical hymns (Christoph Luxenberg). As of today, both theories have been widely discredited (see here). Both the manuscript evidence and scholarly analysis on the Qur’an itself suggests that the Qur’anic Text as it exists today dates from the mid-7th century – which is generally in line with what Muslim tradition has always maintained.

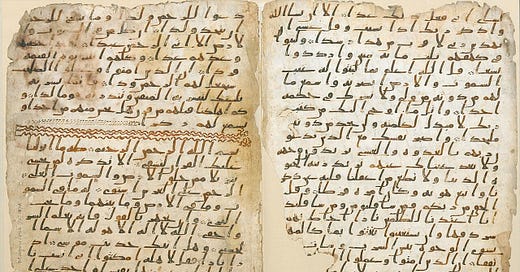

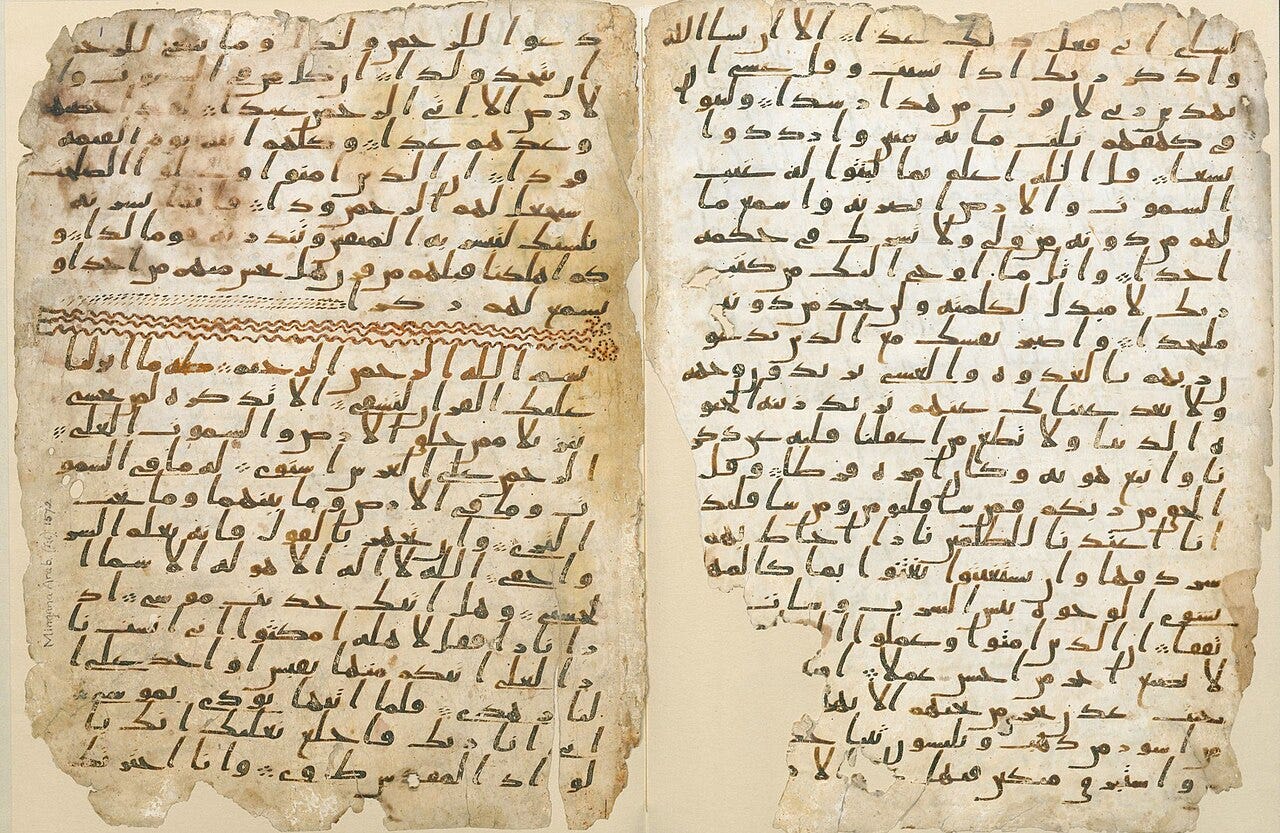

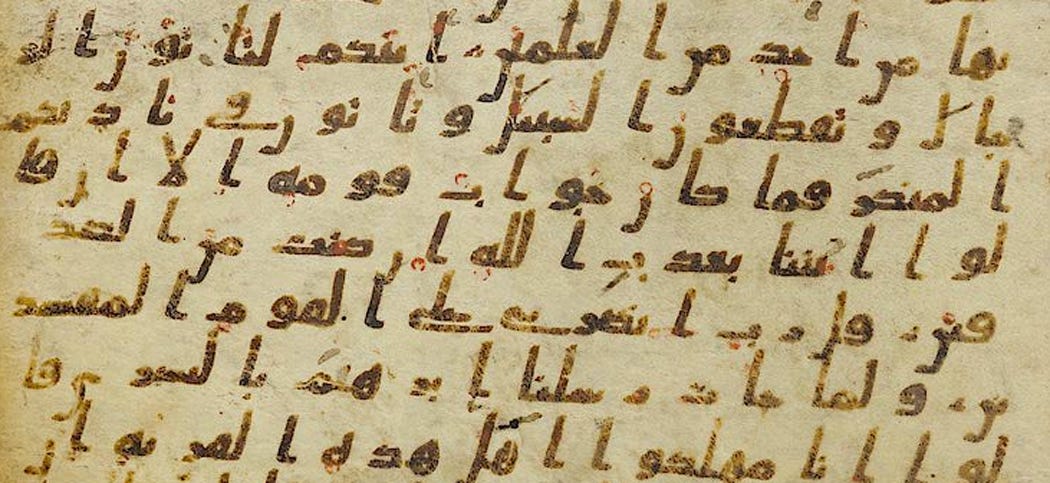

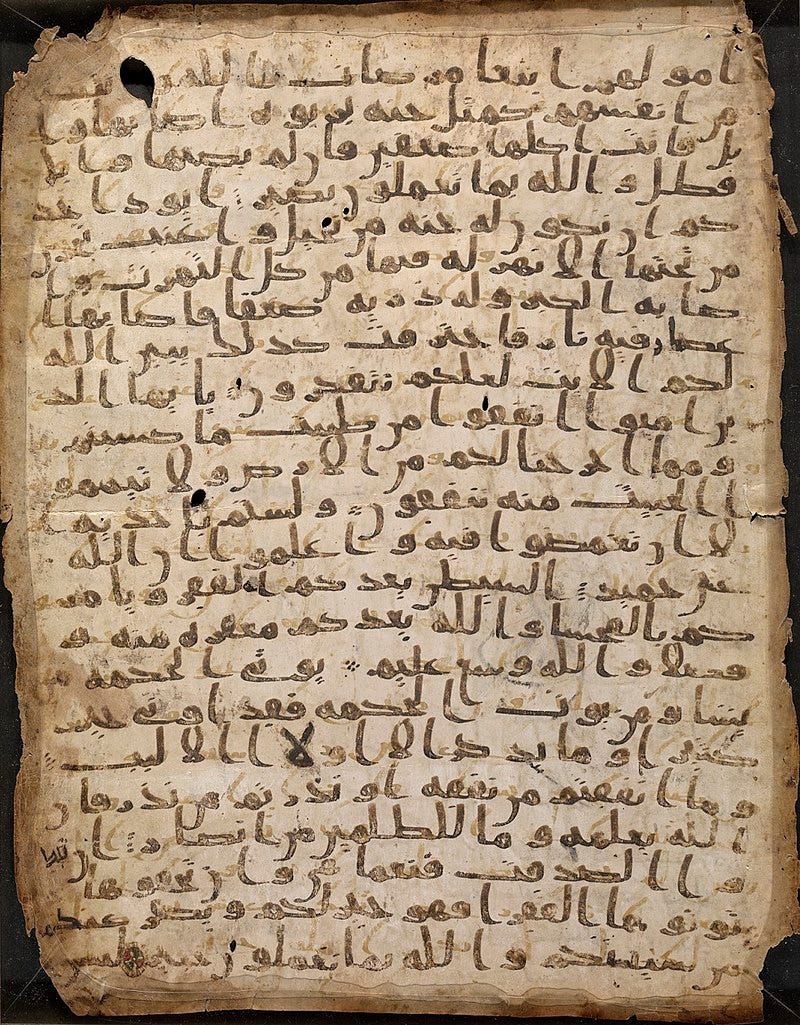

The earliest known manuscripts of the Uthmanic Codex of the Qur’an – the present day Qur’an – are as follows:

1. University of Birmingham Manuscript – carbon dated to the period 568-645 AD

2. Tubingen University Manuscript – carbon dated to the period 625-673 AD

3. Sanaa Manuscript – carbon dated with 68% probability to the period 624-656 and 95% probability to the period 578-669

Several tests on a Koranic manuscript called “Sanaa 1” (including a new test that Mohsen Goudarzi and I will publish soon) have dated it to the first half of the 7th Century.

Behman Sadeghi (Professor at Stanford University), The Origins of the Koran, BBC July 2015 Online)

Scholarly analyses of the Qur’an and the Hadith literature (circulating and compiled 200-300 years after Muhammad’s death) show that the Qur’anic Text dates from the mid-7th century – in general agreement with Muslim sources and tradition. If the Qur’an dates from a later period, then one would expect to see considerable overlap in content between the Qur’an and the Hadith literature that originated in these 300 years. There are substantial differences between the content of the Qur’an and the Hadith as demonstrated by Fred Donner. For example, the Hadith literature is full of references to the political authority of the Caliphs while the Qur’an has nothing to say about political leadership:

A much more natural way to explain the Qur’an’s virtual silence on the question of political leadership is to assume that the Qur’anic Text, as we now have it, antedates the political concerns enshrined so prominently in the hadith literature. This is what we might expect if the Qur’an text is the product of the time of Muhammad and his immediate followers.”

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Narratives of Islamic Origins, 46)

The Hadith literature is full of anachronisms – referring to events that happened after Muhammad lived and operated. Meanwhile, the Qur’an shows no signs of anachronisms and never refers to events that took place after Muhammad’s lifetime.

In the Qur’an, on the other hand, we find not a single reference to events, personalities, groups, or issues that clearly belong to periods after the time of Muhammad – ‘Abbasids, Umayyads, Zubayrids, ‘Alids, the dispute over free will, the dispute over tax revenues and conversion, tribal rivalries, conquests, etc. This suggests that the Qur’an, as it now exists, was already a “closed” body of text by the time of the First Civil War (34-41/656-661), at the latest.

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Narratives of Islamic Origins, 49)

The evidence reviewed above, which is fairly straightforward, seems to point clearly to a relatively early date for the crystallization of the Qur’an text, and implies that this event must have been completed before the First Civil War (34-41/656-661). Moreover, certain elements in the Qur’an’s vocabulary (particularly its use of fulk), and some other features (such as its attitude toward ritual) suggest that it crystallized not in the Fertile Crescent, but in the Hijaz… It does seem clear that the Qur’an text, as we now have it, must be an artifact of the earliest historical phase of the community of Believers, and so can be used with some confidence to understand the values and beliefs of that community.

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Narratives of Islamic Origins, 61)

The examples given above appear to me sufficient to warrant the view that the compilation and redaction of the Qur’an under ‘Uthman (unanimously supported by tradition) is, if not proven, then at least extremely possible…Even if the Qur’an was not compiled under ‘Uthman (d. 656), then the compilation must have taken place no more than a few decades later. In any case, as von Bothmer has shown, we possess the fragments of a Quranic manuscript from Sanaa that dates back to the second half of the first century AH and contains the ‘Uthmanic text, without any variants as far as we know, and even includes the first and last surahs, typically absent from non-‘Uthmanic codices.

Gregor Schoeler (Former Professor and Chair of Islamic Studies at the University of Basel), (“The Codification of the Qur’an,” in Angelika Neuwirth and Gerard Bowering (ed.), The Qur’an in Context, 797-794: 792)

C. Ten Surprising Facts about the Qur’an

The Qur’an’s kitab is not a book in the generally accepted sense of a closed corpus. Rather, it is the symbol of a process of continuing divine engagement with human beings – an engagement that is rich and varied, yet so direct and specific in its address that it could never be comprehended in a fixed canon nor confined between two covers…The logic of the Qurʾān’s own approach demonstrates the impossibility of understanding al-kitāb as a fixed text, a book.

Daniel A. Madigan, (The Qur’an’s Self-Image, 165)

1. The word “qur’an” as used in the Qur’an means “recitation” and does not refer to the standardized written Qur’an Text as it exists today: the Qur’an as Text is a later development. In the earliest period, the word “qur’an” referred to any verse or set of verses that Muhammad revealed and recited on a specific occasion – and this is why the term qur’an is often used in Qur’anic verses in the indefinite form. The Qur’an in its oral form actually rejects the entire notion of it being a fixed, closed and written text that is sent by God “all at once” to the people so they may read it themselves:

And even if We had sent down to you, [O Muhammad], a written scripture on a page and they touched it with their hands, the disbelievers would say, “This is not but obvious magic.”

Holy Qur’an 6:7

The People of the Kitab ask you to bring down to them a book from the heaven. But they had asked of Moses [even] greater than that and said, “Show us God outright,” so the thunderbolt struck them for their wrongdoing. Then they took the calf [for worship] after clear evidences had come to them, and We pardoned that. And We gave Moses a clear authority.

Holy Qur’an 4:153

And those who disbelieve say, “Why was the recitation (qur’an) not sent down to him all at once?” Thus [it is] that We may strengthen thereby your heart. And We have arranged it in order.

Holy Qur’an 25:32

To Muḥammad’s interlocutors, a divine pronouncement must, almost by definition, be complete. Yet the Qurʾān comes only, as the commentators like to say, responsively (jawāban liqawlihim), in installments (munajjaman) according to situations and events in order that the Prophet will be able to address God’s response to whatever objection is being raised, whatever question is being asked ( q 25:33). In this context they quote q 17:106: “…and in the form of a recitation that we have divided up (faraqnāhu) that you might recite it to the people at intervals (ʿala mukthin), and we have indeed sent it down.” In rejecting the claim that it should be sent down “as a single complete pronouncement” the Qurʾān is asserting its fluidity and its responsiveness to situations. It is refusing to behave as an already closed and canonized text but insists on being the authoritative voice of God in the present.

Daniel A. Madigan, (“Kitab”, in Encyclopedia of the Qur’an 2013, Read Online)

2. The Qur’an is not inherently a “book”; it is “spoken word”: The word qur’an means “recitation” and originally refers to oral recitations uttered by Prophet Muhammad over a period of 23 years, in a variety of situations; addressed to different audiences (his family, his community, nonbelievers, Jews, Christians, his enemies); responding to specific questions and statements raised by his contemporaries. The Qur’an in its original oral form – as it was being recited by Muhammad in his own lifetime – did not exist as a “written text” or a “book” and did not define itself as a closed text or process; instead, the oral Qur’an was an open-ended event of revelation in which specific recitations dynamically responded to ongoing events and more updated recitations were uttered by the Prophet as time and circumstance required.

The Qur’an in its emergent phase is not a pre-meditated, fixed compilation, a reified literary artifact, but a still-mobile text reflecting an oral theological-philosophical debate between diverse interlocutors of various late antique denominations…The oral Qur’an (to use a loose expression) may be compared to a telephone conversation where the speech of only one party is audible, yet the unheard speech of the other is roughly deducible from the audible one. Indeed, the social concerns and theological questions of the listeners are widely reflected in the Qur’an text pronounced by the Prophet’s voice. To approach the text as a historical document thus would demand the researcher to investigate Muḥammad’s growing and changing public, listeners who belonged to a late antique urban milieu, many of whom must have been aware of and perhaps involved in the theological debates among Jews, Christians, and others in the seventh century… What is striking here is that the Qur’an did not subscribe to the concept of a written manifestation of scripture but established a new image, that of an “oral scripture”; in William Graham’s words, “The Qur’an has always been pre-eminently an oral, not a written text” (2003:584). Daniel Madigan justly claims that “nothing about the Qur’an suggests that it conceives of itself as identical with the kitab (the celestial book)” (cited in Sinai 2006:115), that is to say the Qur’an in no phase of its development strove to become a closed scriptural corpus.

Angelika Neuwirth, (“Two Faces of the Qur’an: Qur’an and Mushaf” in Oral Tradition, 25/1 (2010): 141-156: 142)

3. The Qur’an never claims to be the entirety of God’s Speech, Words, Book, Signs, or Guidance: The Qur’an explicitly denies that God’s Words can be exhausted or captured by any human words or writing. The Qur’an constantly declares that the Signs (ayat) of God – a term used for the Qur’an’s own verses – are found throughout the Cosmos and within the souls of human beings:

And if whatever trees upon the earth were pens and the sea [was ink], replenished thereafter by seven [more] seas, the Words of God would not be exhausted. Indeed, God is Exalted in Might and Wise.

Holy Qur’an 31:27

Say, “If the sea were ink for [writing] the Words of my Lord, the sea would be exhausted before the Words of my Lord were exhausted, even if We brought the like of it as a supplement.”

Holy Qur’an 18:109

The sending down of the Kitab is from God, the Exalted in Might, the Wise. Indeed, within the heavens and earth are Signs (ayat) for the believers. And in the creation of yourselves and what He disperses of moving creatures are Signs (ayat) for people who are certain. And [in] the alternation of night and day and [in] what God sends down from the sky of provision and gives life thereby to the earth after its lifelessness and [in His] directing of the winds are Signs (ayat) for a people who reason.

Holy Qur’an 45:2-6

And on the earth are Signs (ayat) for the certain, and in your own souls. Then will you not see?

Holy Qur’an 51:20-21

4. Prophet Muhammad did not produce or publish a “book” (text) of the Qur’an: While it was common for Muhammad’s companions to memorize these recitations and write some of them down on rocks, leaves, parchment, etc., Prophet Muhammad never collected the Qur’anic recitations into a single document and never published the Qur’anic recitations as a “book”:

The revelations remained in a state of flux during the Prophet’s lifetime: verses and surahs were added, while others were “abrogated.” It is thus hardly conceivable that before his death the Prophet established a final edition of the revealed text, or that he constantly brought one version of it up to date. As has been shown, this would have been in complete contrast with the methods employed by ancient Arabic poets.

Gregor Schoeler (Former Professor and Chair of Islamic Studies at the University of Basel), (“The Codification of the Qur’an,” in Angelika Neuwirth and Gerard Bowering (ed.), The Qur’an in Context, 797-794: 784)

Neither strand of the tradition represents the text at the time of the Prophet’s death as having existed in a physical form that would indicate that Muḥammad had all but finished preparing the definitive document of revelation. The scraps of wood, leather and pottery, the bones and the bark on which the revelations were apparently written down seem to indicate that the Prophet did not have in mind producing the kind of scroll or codex that was characteristic of Jewish and Christian use in other places.

Daniel A. Madigan, (“Kitab”, in Encyclopedia of the Qur’an 2013, Read Online)

5. The “Qur’an Text” as it exists today was collected by Zayd b. Thabit and compiled into a standard version Qur’an Text under Uthman (d. 656). In fact, there was much resistence to the prospect of collecting the Qur’an into a single volume. In an early report, Zayd b. Thabit describes a conversation he had with Abu Bakr about ‘Umar wanting the collect the Qur’an into a text, even though the Prophet Muhammad had ordered no such thing:

Abu Bakr said: “Umar came to me and said ‘The slaughter has taken a great toll on the reciters of the Qur’an on the day of Yamama and I fear lest a similar toll fall reciters in every place of battle and as a result much of the Qur’an be lost. I think you should give orders for the Qur’an to be collected.'” [Abu Bakr] said, ‘I asked Umar how I could do a thing which the Messenger of God had not done.’ Umar replied, ‘By God it is a good thing!’ And he kept on me about it until I came to be of the same opinion about it as he was.

Abu Bakr continued: ‘You are an intelligent young man about whom we have no doubts; moreover you used to write down the revelations for the Messenger of God. So track down the Qur’an and collect it.’

Zayd said, “I said [to Abu Bakr] ‘By God if you had charged me with moving a mountain that would not have been more burdensome for me than what you have commanded me with regard to collecting the Qur’an! How can you do something which the Messenger of God did not do?’ He said, “By God it is a good thing!” And he kept on at me about it until God opened my heart to accept what He had already convinced Abu Bakr and Umar of.”

(Kitab al-Mabani, ed. Jeffery in “Two Muqaddimas to the Qur’anic Sciences, 17-18; quoted in Daniel A. Madigan, The Qur’an’s Self-Image, 26-27)

Today’s Qur’an Text does not arrange the verses and the chapters in their original chronological order, nor does it disclose the original historical context of the Qur’anic recitations as recited by Prophet Muhammad during his lifetime. The present-day Qur’an Text is like an ad-hoc transcript of the various Qur’anic recitations originally recited by Muhammad over 23 years to different audiences in different situations – in which the recitations made in different times and places have been combined into a single volume. But, in its original context and function, the Qur’an is first and foremost an “oral recitation” that is meant to be “heard” and not “read” like a textbook:

The Koran′s own conception of itself is as the liturgical recitation of the direct speech of God. It is a text intended to be read out loud. The written word is secondary and until well into the twentieth century it was, for Muslims, little more than an aide-memoire…in the strictest sense, one cannot read it, one can only hear it. In this context, Angelika Neuwirth speaks of the sacramental character of Koranic recitation. Although Islam does not use this term, it is essentially a sacramental act to take God′s word into one′s mouth, to receive it through the ears, to learn it by heart: the sacred is not simply remembered, the faithful physically take it into their bodies, actually absorb it, much as Christians do Jesus Christ when they take Communion…The text itself, as it stands, is in part the written record, the carefully-edited transcript, of a public recitation, a performance, written down after the fact. The Koran thus does not consist solely of the statements of a single speaker: it incorporates interjections from an audience of believers, or of unbelievers – as well as spontaneous responses to these interjections, which repeatedly lead to abrupt changes of subject.

Navid Kermani, (“Salafism or Philology: The Scholar’s Touch”, Read Online)

6. The Qur’an speaks to and engages with the knowledge of its original historical audience: the Qur’an actually reinterprets, comments upon, and re-tells various Jewish, Christian, and Arabian beliefs, stories, and traditions that were circulating amongst the Christian, Jewish, Sabian, and other communities of the Hijaz and the Fertile Crescent. It is common for the Qur’an to relate, reinterpret, or retell Jewish and Christian stories of prior prophets found in the Old Testament, New Testament, non-canonical gospels, and extra-biblical sources including the Jewish Talmud.

We need to remember that the Qur’ānic age roughly coincides with the epoch when the great exegetical corpora of monotheist tradition were edited and published, such as the two Talmudim in Judaism and the patristic writings in Christianity. These writings, not the Bible, as is often held, are the literary counterparts of the Qur’ān. Daniel Boyarin (2004) repeatedly stresses that the Talmud is — no less than the writings of the Church fathers — imbued with Hellenistic rhetoric. Indeed, the Qur’ān should be understood first and foremost as exegetical, that is, polemical-apologetical, and thus highly rhetorical. The Qur’ān is communicated to listeners whose education already comprises biblical and post-biblical lore, whose nascent scripture therefore should provide answers to the questions raised in biblical exegesis — a scripture providing commentary on a vast amount of earlier theological legacies.

Angelika Neuwirth, (“Two Faces of the Qur’an: Qur’an and Mushaf” in Oral Tradition, 25/1 (2010): 141-156: 142)

7. The Qur’an is NOT the same as the Kitab: The Qur’an refers to legal decrees, rules of conduct, itself, prior revelations through other Prophets, the celestial source of all prophetic revelation, and God’s knowledge of all things and events, etc. as “al-Kitab” – which is usually translated as “the book.” Most Muslims today simply equate the Qur’an Text with “al-Kitab.” However, the word “kitab” as used in the Qur’an does NOT actually mean a physical “book” or “writing.” Instead, the term kitab as used in the Qur’an has a much broader and expansive meaning – kitab is a symbol for God’s guidance, knowledge, authority, and decree in the broader sense and ultimately refers to a heavenly celestial archetype beyond the physical world.

The kitāb of revelation is intimately linked with the same divine knowledge and authority that they symbolize. The fundamental pattern (with associated verbal roots) is this: (a) As creator God knows (‘ilm) the truth (ḥaqq) of all things and is in command (hukm) of all things. The symbol for this knowledge and authority is kitāb… In this respect, the Qurʾān does not present the kitāb as a closed and definable corpus of text, but rather as an ongoing relationship of guidance…The Qurʾān actually rejects certain common conceptions of kitāb. It is reiterated several times that in the ministry of the Prophet there comes to the Arabs (q.v.) “a kitāb from God” (e.g. q 6:19, 114). However, it is also clear that Muḥammad does not consider that the lack of any written text invalidates this claim in any way. When the Prophet is challenged to produce a writing from heaven as proof (q.v.) of his authenticity (q 17:93; see belief and unbelief ), he is told to reply that he is merely a human messenger. In q 6:7 God says, “Even if we had sent down a kitāb on papyrus and they were to touch it with their hands, those who disbelieve would have said, ‘This is clearly nothing but sorcery.’” So when the Qurʾān speaks of itself as kitāb, it seems to be talking not about the form in which it is sent down but rather about the authority it carries as a manifestation of the knowledge and command of God.

Daniel A. Madigan, (“Kitab”, in Encyclopedia of the Qur’an 2013, Read Online)

According to the Qur’an, the Kitab (variously called Kitab, Umm al-Kitab, and Lawh al-Mafuz) is the celestial heavenly archetype and source of all Divine knowledge, guidance, and revelation whereas the Arabic qur’an is merely the verbal manifestation of this eternal celestial Kitab for a certain time, place, and audience. The Qur’an contains numerous verses which say that the Kitab has been “sent down” (tanzil) or “unpacked” (tafsil) in the form of an Arabic qur’an. This is why the Qur’an makes a clear distinction between the “Kitab” and the “Arabic Qur’an”:

Alif, Lam, Ra. These are the Signs (ayat) of the Clear Kitab (al-kitab al-mubin). Indeed, We have sent it down (anzalnahu) as an Arabic recitation (qur’anan ‘arabiyan).

Holy Qur’an 12:1-2

By the Clear Kitab (al-kitab al-mubin). Indeed, We have made it (ja‘alnahu) an Arabic recitation (qur’anan ‘arabiyan)

Holy Qur’an 43:2-3 (see similar verses 15:1, 44:1-2, 26:2)

Mankind was one single nation, and God sent Prophets with glad tidings and warnings; and with them He sent the Kitab (anzala ma‘hum al-kitaba) in truth, to judge between people in matters wherein they differed;

Holy Qur’an 2:213/p>

Contrary to the traditional Islamic identification of both terms, in some middle and late Meccan texts kitab and qur’an are actually kept carefully distinct. Even though qur’an from a certain stage on can refer to the corpus of recitations that have so far been revealed – a corpus, though, that has not yet reached closure -, it frequently specifies merely the characteristic mode of display in which al-kitab is being delivered unto and by Muhammad…Thus, whereas al-kitab evokes a celestial mode of storage – i.e. writing -, qur’an points to an earthly mode of display. At least by implication, there might be ways other than recitation to display al-kitab…The heavenly kitab is, as it were, ‘unpacked’ in the form of an Arabic recitation, rather than having been composed in Arabic from eternity on… One probably ought to say that the Qur’an considers itself both a translation and an interpretation of the kitab.

Nicholai Sinai, (“Qur’anic self-referentiality as a strategy of self-authorization,” in Stefan Wild (ed.), Self-Referentiality in the Qur’an, 2006, 122-24)

The Qur’an even suggests that the revelation of the Kitab came to the Prophet’s heart (the spiritual organ of intuitive understanding according to the Qur’an) in a non-verbal form of “spirit” and “light” and not in the verbal or audible form of Arabic words and letters:

And that We have inspired you [Muhammad] with a Spirit (ruh) from Our Command. You did not know what was the Kitab and what was the Faith. But We have made it a Light (nur) by which We guide such of our Servants as We will. And verily, you guide to a Straight Path.”

Holy Qur’an 42:52

And indeed, it is the sending down (tanzil) from the Lord of the Worlds

The Trustworthy Spirit (al-ruh al-amin) has brought it down (nazala biha)

Upon your heart (‘ala qalbika) that you may be of the warners

In a clear Arabic language (bi-lisanin ‘arabiyyin)Holy Qur’an 26:193-195

8. Prophet Muhammad was much more than a mere “delivery service” for the Qur’an: The roles and responsibilities of Prophet Muhammad outlined in the Qur’an are numerous (as explained in detail here); Prophet Muhammad’s function and authority includes much more than merely reciting the Qur’anic revelations. The Prophet was also responsible for teaching God’s guidance and judging over the believers with wisdom, interpreting and explaining the meaning of the Qur’anic recitations as they came, purifying the believers, praying for the believers, accepting the believers’ offerings and repentance on God’s behalf, etc.

Certainly did God confer a great favour upon the believers when He sent among them a Messenger from themselves, reciting His Signs, and purifying them, and teaching them the Kitab and the Wisdom, although they had been before in manifest error.

Holy Qur’an 3:164 (see also 62:2, 2:129, 2:151)

And We have sent down unto you (also) the Reminder; that you may explain clearly to mankind what was sent down for them, and that they reflect.

Holy Qur’an 16:44 (see also 16:64, 14:4)

Explication of the divine intention of the revelation was among the functions that the Qur’an assigned to the Prophet. The Prophet functioned as the projection of the divine message embodied in the Qur’an. He was the living commentary of the Qur’an, inextricably related to the revelatory text. Without the Prophet the Qur’an was incomprehensible, just as without the Qur’an the Prophet was no prophet at all.

Abdul Aziz Sachedina, (“Scriptural Reasoning in Islam”, Journal of Scriptural Reasoning, 5/1 2005)

9. The Qur’an recognizes people of different faiths as Believers and as muslims: A number of mistranslations occur when the Arabic Qur’an is translated to English (read here for a list of common mistranslations). For example, the word islam as used in the Qur’an does not mean “the formal religion of Islam” as understood today.

In other words, muslim in Qur’anic usage means, essentially, a committed monotheist, and islam means committed monotheism in the sense of submitting oneself to God’s will. This is why Abraham can be considered, in this Qur’anic verse, a hanif muslim, a “committed, monotheistic hanif.” As used in the Qur’an, then, islam and muslim do not yet have the sense of confessional distinctness we now associate with “Islam” and “Muslim”; they meant something broader and more inclusive and were sometimes even applied to some Christians and Jews, who were, after all, also monotheists (Q. 3:52, 3:83, and 29:46).

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam, 71)

The term islam as used in the Qur’an in the below verses simply means “submission to God” and embraces multiple religious and spiritual traditions and paths. Every prophet of the past, the disciples of Jesus, past communities, Jews and Christians, as well as the followers of Muhammad are called “muslims” (submitters).

Seek they other than the religion of God (din Allah), when unto Him submits whosoever is in the heavens and the earth, willingly or unwillingly? And unto Him they will be returned.

Holy Qur’an 3:85

Indeed, the religion in the sight of God is submission (islam) And those who were given the Kitab did not differ except after knowledge had come to them – out of jealous animosity between themselves. And whoever disbelieves in the Signs of God , then indeed, God is swift in [taking] account.

Holy Qur’an 3:19

And whoever desires other than submission (islam) as religion – never will it be accepted from him, and he, in the Hereafter, will be among the losers.

Holy Qur’an 3:85

Throughout this work, I have translated the terms muslim and islam in accordance with their original connotations, namely, “one who surrenders [or “has surrendered”] himself to God”, and “man’s self-surrender to God”…It should be borne in mind that the “institutionalized” use of these terms — that is, their exclusive application to the followers of the Prophet Muhammad — represents a definitely post-Quranic development and, hence, must be avoided in a translation of the Quran.

Muhammad Asad, (The Message of the Qur’an: Translated and Explained by Muhammad Asad, Gibraltar 1984, 885, n. 17)

In fact, the Qur’an extends the possibility of salvation to people of all faiths – the believers in the revelation to Muhammad, Jews, Christians, Sabians, Magians, and anyone who has faith in God and the Day of Judgment. The term “believer” (mu’min) was the name for Prophet Muhammad’s community and Jews and Christians were recognized as “believers” alongside Muhammad’s followers.

For each We have appointed a divine law and a traced-out way. Had God willed He could have made you one community. But that He may try you by that which He hath given you (He hath made you as ye are). So vie one with another in good works. Unto God ye will all return, and He will then inform you of that wherein ye differ.

Holy Qur’an 5:48

Lo! Those who believe (in that which is revealed unto thee, Muhammad), and those who are Jews, and Christians, and Sabians – whoever believeth in God and the Last Day and doeth right – surely their reward is with their Lord, and there shall no fear come upon them neither shall they grieve.

Holy Qur’an 2:62

Closer examination of the Qur’an reveals a number of passages indicating that some Christians and Jews could belong to the Believers’ movement – not simply by virtue of their being Christians or Jews, but because they were inclined to righteousness. For example, Q. 3:199 states, “There are among the people of the book those who Believe in God and what was sent down to you and was sent down to them…” Other verses, such as Q. 3:113-116, lay this out in greater detail. These passages and other like them suggest that some peoples of the book Christians and Jews-were considered Believers.

Fred Donner (Professor of Near Eastern History – University of Chicago), (Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam, 69-70)

The word “kafir” is often translated as “unbeliever”, but the meaning of “kafir” is literally “one who covers/conceals.” The Qur’an does not use the word “kafir” in a blanket sense for everyone who is not Muslim (as we have seen the word muslim applies to people of other faiths too); but rather, the Qur’an labels as “kafir” those people who are ungrateful for God’s favours and knowingly conceals the truth. This is why “kufr” (covering, disbelief) is always contrasted in the Qur’an with “shukr” (gratefulness).

10. The Qur’an never claims to be “easy to understand” or “a simple book”: The Qur’an’s verses are full of parables (amthal) and always addressed to people of intellect (ulu al-albab), the knowers (‘alimun), or the people of knowledge (ulu al-‘ilm) and exhorts its listeners to think, reflect, ponder, and analyze its verses. Some verses even say that the inner meaning of the Qur’an is only known to a special class of possessors of sacred knowledge (‘ilm), while other verses (Qur’an 6:25, 17:46, 18:57) say that the unbelievers will not comprehend the meaning of the Qur’an.

It is an honorable Qur’an in a Hidden Kitab. None touch it except the purified.

Holy Qur’an 56:78

No one knows its inner meaning (ta’wil) except for God and those who are firmly rooted in knowledge.

Holy Qur’an 3:7

And We have certainly presented for the people in this Qur’an from every [kind of] example – that they might reflect.

Holy Qur’an 39:27

A Kitab which We have revealed to you, full of blessings, [O Muhammad], that they might reflect upon its Signs and that those of understanding would be reminded.

Holy Qur’an 38:29

And those parables (amthal) We strike for humankind so that they may reflect.

Holy Qur’an 59:21

And these examples We present to the people, but none will understand them except the Knowers (‘alimun).

Holy Qur’an 29:43

And of His signs (ayat) is the creation of the heavens and the earth and the diversity of your languages and your colors. Indeed in that are signs (ayat) for the Knowers (‘alimun).

Holy Qur’an 30:22

Nay, rather it [the Qur’an] is Clear Signs (ayat) in the breasts of those who are given knowledge (alladhi utu al-‘ilm).

Holy Qur’an 29:49

Then do they not reflect upon the Qur’an? If it had been from [any] other than God, they would have found within it much contradiction.

Holy Qur’an 4:82