10 Crazy Stories from Ismaili History

The future of the Ismaili Faith rests in the hands of the youths of your age and mine. Are we to follow the example of those, who in Egypt, Iran and Sind raised the flag of Ismaili Imams high enough for the world to see its glory? I say, ‘Yes’. We should not fail where our ancestors achieved glorious success.

– Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan

Ismaili history is littered with an embarrassment of heroes. From our forty-nine Imams to the followers inspired by them, courageous individuals have pushed boundaries to inform the world about Ismaili theology, put their lives on the line to save the Ismaili community, and fought insurmountable odds to keep the light of Ismailism alive.

Until recently, Ismaili Imams and their followers have been hunted, killed and even tortured, throughout their heart wrenching history, often hiding and even vanishing for generations to save themselves. For example, Al-Sijistani, one of Ismaili history’s most important Da‘is, wrote ground-breaking work on Ismaili theology but was killed for his faith, without so much as a glimpse of his Imam. However, thanks to his sacrifice and, those of others like him, Ismailis today enjoy a rich and wonderful intellectual heritage.

This article pays homage to some of these heroes from Ismaili history with ten crazy stories that will move you!

1. Hazrat Zaynab bint ‘Ali

Among Shi’a Muslims, the story of Karbala is well known and commemorated by many during the Islamic month of Muharram.

Despite the Prophet Muhammad’s designation of Hazrat ‘Ali as his spiritual and temporal successor, political machinations of powerful figures of the time conspired to have Imam ‘Ali side-lined. Although he eventually, but briefly, took on the leadership of the entire Muslim community, after his murder, his heirs were vigorously persecuted and even condemned from the pulpit as a matter of “state” policy by prominent leaders like Muawiya. When Hazrat ‘Ali’s son, and only living grandson of the Prophet, Imam al-Husayn, was invited by the people of Kufa to lead them, he asked them if they were sure that was their wish. Only after they re-affirmed their allegiance to him did he agree to lead them. While en route to Kufa — accompanied by his supporters and entire family, including many women and children — his group of hundreds was intercepted by a force of more than twenty thousand who first cut off their water supply and then attacked them.

Abandoned by the supporters who had promised him their allegiance, Imam al-Husayn and his family were horrifically massacred at the Battle of Karbala. He was decapitated and his head flaunted in Kufa — before it was presented to Yazid, on a platter.

Qurra’ b. Qays at- Tamimi, a member of the Umayyad army, is reported by Abu Mikhnaf as saying that he could never forget the scene when Husayn’s sister Zaynab passed by the mutilated body of her brother; she cried in hysterical fits, saying:

‘O Muhammad! O Muhammad! The angels of Heaven send blessings upon you, but this is your Husayn, so humiliated and disgraced, covered with blood and cut into pieces; and, O, Muhammad, your daughters are made captives, and your butchered family is left for the East Wind to cover with dust?’

S.H.M. Jafri, The Origins and Development of Shia Islam, (p. 132)

But Imam Husayn was not the only martyr that day. “The dead included Imam al-Husayn’s sons, including the six month old infant ‘Ali Asghar, Imam ‘Ali ibn Abu Talib’s sons, and Pir Imam al-Hasan’s children. ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin was the only surviving male member of Imam Husayn’s family, who was sick during the battle and saved from execution by Hadrat Zaynab’s intervention.” (Mourning for Marifa)

Hazrat Zaynab, the only daughter of Hazrat Fatima and Hazrat ‘Ali, rose up and, disregarding her own safety, threw her body over her nephew, Imam Zayn al-Abidin, defying the would-be murderers to first kill her if they wanted to kill Imam Zayn al-Abdidin . Taken aback, the men instead imprisoned and delivered the remaining family members of the martyred Imam to Yazid, in the capital, to decide their fate. However, upon entering the capital and in the full view of all the dignitaries, Hazrat Zaynab delivered an impassioned, impromptu speech — rhyming it in her father Imam ‘Ali’s style — reducing all observers to tears. Due to her courage, persistence and outspoken defence of her nephew, she saved his life and thereby the Ismaili Imamat:

The embittered speech delivered by al-Husayn’s sister, Zaynab, reportedly moved all around her to tears, and her unyielding defense of her family and their honor after they were taken captive reportedly evoked the admiration even of her enemies.

Maria Dakake, Charismatic Community, (p. 219)

Reza Shah-Kazemi, Justice and Remembrance, (p. 2)

2. La‘b

The period of satr (concealment), prior to the advent of the Fatimid empire, was one marked with extreme danger. The Abbasid caliphs relentlessly hunted down the Imams, hoping to eliminate the entire family line. The Imams, however, moving from place to place, evaded capture.

When the enemy forces approached Ramla, they came across La‘b, whom they knew was a devoted, long-time servant of Imam al-Mahdi and who also knew where the Imam was. During her interrogation, despite threatening her and her children’s lives, she never relented, never once betraying her Imam. For her loyalty, both she and all her children were slaughtered. Once again the Ismaili Imamat was saved by the brave loyalty of an Ismaili woman. Imam al-Mahdi later went on to found the Fatimid Caliphate and the rest, as it is said, was history. (Delia Cortese, Women and the Fatimids, 25)

3. Imam al-Mahdi comes to power and founds the Fatimid State

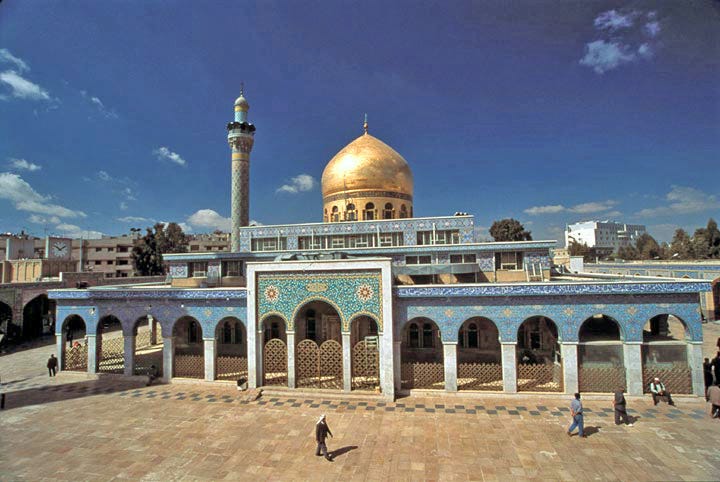

After the death of Imam Muhammad b. Ismail, but before the rise of the Fatimid Empire, the Ismaili Imams hid in Salamiyyah, Syria.

When the Abbasid manhunt for the hiding Ismaili Imams grew a little too close for comfort, Imam al-Mahdi and the Da‘wah were forced to move out of Syria. One Ismaili Da‘i, al-Husyan b. Zikrawyah, captured by the Abbasids and “interrogated under torture,” revealed Imam al-Mahdi’s identity and whereabouts allowing the Abbasids to intensify and expand their chase for the Imam.

In 904, starting in Syria, Imam al-Mahdi travelled to Palestine and then, after the Abbasids executed more Da‘is, to Egypt. However, once again, the Abbasids advanced on Imam al-Mahdi’s location, forcing him to relocate again.

While many of the Imam’s companions expected him to move to Yemen, Imam al-Mahdi instead travelled deeper into North Africa to avoid potential military conflicts with the Abbasids. However, not surprisingly, North Africa was also not safe for the Imams, since the Sunni Aghlabids ruling North Africa, “were instructed by their Abbasid overlords to search for the Ismaili Imam and his companions.” Still disguised as merchants, Imam al-Mahdi, his brother Ja’far, and son, the future Imam al-Qaim, took refuge on the far west coast of Africa in Morocco.

During this time, one of the head Da‘is of the Ismaili Da‘wah in North Africa, Abu ‘Abd Allah Shi‘i — who was largely responsible for establishing the territorial foundation of the Fatimid Caliphate, directed his teaching towards the warlike North African Berber clans, steadily securing their allegiance to Imam al-Mahdi, with whom Shi‘i was in touch. Supported by these new forces, Ismaili dai’s overthrew North African emirs, including the Aghlabid Emir, clearing the way for the Imam to establish the dawlat al-haqq or the “the kingdom of the truth.”

After years of warfare, Shi‘i minted new coins heralding the arrival of the hujjat Allah or “proof of God,” and, with an army of Berbers, escorted the Ismaili Imam and his family from Morocco to Raqqada which later became new capital of the young Fatimid State. Upon meeting and seeing the Imam, his Lord, Shi‘i was “bathed in tears” and reaffirmed his allegiance. The following day, in his tent, the Imam granted an audience to each and every individual troop member who also pledged their allegiance. Then on Friday January 5th, 910 CE, Imam al-Mahdi was declared the “Commander of the Faithful” and the first Caliph of the newly found Fatimid Caliphate.

An Ismaili eyewitness, the Da‘i Ibn al-Haytham, recounts the arrival of the Imam to his new North-African kingdom:

It was he whose excellence could not be hidden and ‘the truth has now arrived and falsehood has perished’ [17.81]. The stars declined and the Alive and Self-subsistent appeared. Abu-‘l-‘Abbas went out and we went out with him and met the lord on the mountain pass of Sabiba. I cannot forget his auspicious appearance, the splendor of his light, the brightness of his face, the elevation of his rank, the perfection of his build, and the resplendent beauty in his dawn. If I were to say that the lights that shine were created from the surplus of his light, I would have voiced the truth and the manifest reality. Abu’l-‘Abbas dismounted before him, may the blessings of God be upon him, and kissed the earth. He lay on the ground in front of him, and his brother Abu ‘Abdallah dismounted for him, as did all of the friends from the Kutama and the others of their followers. No one was left riding except the Commander of the Faithful, may the blessings of God be upon him, the sun most radiant, and [his son] the shining moon and glittering light, Abu’l-Wasim. These two, may the blessings of God be on them both, were the light of the world…. The earth began to shine with his light and the world was illuminated by his advent, and the Maghrib excelled because of his presence in it and his having taken possession of it.

Wilfred Madelung and Paul Walker, The Advent of the Fatimids — A Contemporary Shi’i Witness, (p. 167)

4. Al-Mu’ayyad al-Shirazi

Called a “towering mountain of knowledge” by Imam al-Mustansir, al-Mu’ayyad al-Shirazi was the last and greatest from a dynasty of Da‘is. His ancestors had supported and promoted hidden Ismaili Imams long before the Fatimid era, of which Imam al-Mustansir was the last Nizari Imam. As a bab or “gate” to the Imam (a spiritual rank second only to the Imam himself), he was the spiritual mother of the Ismaili community (akin to the “Pir” of the Satpanth tradition) and, as such, looked after the spiritual welfare of the jamat.

Fearless in his commitment to the Imam in faraway Fatimid Cairo, the Persian Da‘i’s life is replete with stories of banishment, house arrest, nearly-missed executions, rejection by the non-Ismaili community in his home of Persia and even victim of intrigue and marginalization by the Cairo-based Fatimid bureaucracy. Despite all these impediments and despite the Abbasid caliph sending emissaries to woo the devoted Da‘i to the Sunni cause with sweet words, robes and promises, Shirazi never once wavered from his loyal devotion to the Imam.

On one occasion, after having been banished from Shiraz (Iran), Shirazi, travelling the back roads incognito, escaped to Ahvaz where he came across an abandoned, decrepit masjid. Despite being exiled for proselytizing the Ismaili faith, he could not resist restoring the masjid and inscribing the Ismaili Imams’ names in brilliant gold in its woodwork. Then Shirazi asked a team of twenty Ismaili muezzins to loudly proclaim the Shia call to prayer while the Sunni population of the town looked on in amazement and horror. Simultaneously, Shirazi had his Ismaili Daylami soldiers surround the masjid forestalling any confrontation with the townspeople. Not one to leave well enough alone, he then offered the Friday sermon proudly in the name of the teenage Fatimid Ismaili Imam al-Mustansir, in Cairo.

Not surprisingly, this act of defiant allegiance to the Imam of the Time prompted the chief qadi of the village to lodge a formal complaint with the Abbasid caliph and poor Shirazi was once again banished.

To learn more about the remarkable, irrepressible and inspirational al-Shirazi, please read this summary of his memoirs, published by the Institute of Ismaili Studies.

5. Hasan-i Sabbah

Though in the midst of turbulent times, Imam al-Mustansir I’s Imamat was one of the longest Imamats in Ismaili history and marked the peak of Ismaili political influence. The khutba in Mecca, Medina, and even Baghdad (the centre of Abbasid power) was read in the name of the Fatimid Imam al-Mustansir and even the Ka’ba in Mecca was adorned in the Fatimid livery of white and gold rather than Abbasid black (as it does today).

Unfortunately, his reign also experienced a heart-breaking low as the wazirate, led by Sunni generals Badr al-Jamali and al-Afdal al-Jamali usurped more and more power from the Imam — seizing the army, the judiciary and even the leadership of the Da‘wah. The power grab culminated with a coup d’etat that saw Imam Nizar removed from the Fatimid Caliphal throne, seized and then executed, or, horrifically, even buried alive (Peter Willey, The Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, p.16). One witness to this fatal deterioration of the Imam’s power was the prescient Ismaili Da‘i Hasan-i Sabbah. Recognizing a catastrophe in the making, he fought vigorously for Imam Nizar’s rights. A Fatimid Cassandra, his unwavering support for the Imam was met with resistance from Ismaili and non-Ismaili Jamali partisans alike, leading to his exile from the Fatimid capital after just a few years.

Undeterred and with resolute determination, Hasan-i Sabbah built a parallel, yet independent, administration, with its seat at the impregnable mountain castle of Alamut. His foresight, courage and boldness would, in just a short time, make him the saviour of the Nizari Ismailis. His story is perhaps best told by Peter Willey in his The Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria:

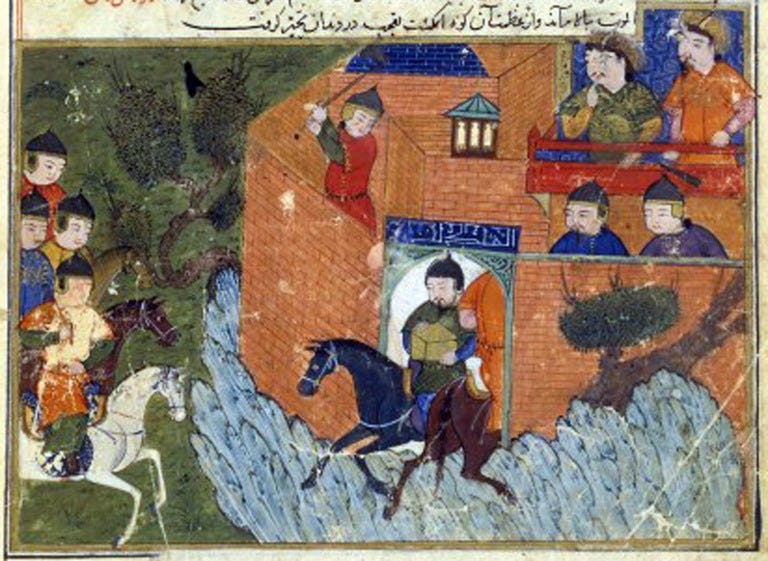

It was nearly noon on a hot day in the early summer of 1090. Mahdi, the lord of the castle of Alamut, was beginning to sweat a little. He had spent the last few weeks in Qazvin, a modest town some 60 km away in the Daylaman region of northern Iran…

It did not seem long before they saw the great mass of the Taleqan range rising sharply before them in the clear blue sky. Soon they arrived at Shirkuh where the Taleqan and Alamut rivers join to form the fast-flowing Shahrud. This was the summer entrance to the valley of Alamut, and the escort rode through the clear blue waters that were only waist high. In winter it was impossible for any horse or foot soldier to cross the thundering stretch of water.

Once inside the gorge through which the track led, Mahdi felt more secure. The rock walls of the narrow opening towered up some 350 metres and guards, stationed at the fortifications built halfway up the rock walls, saluted their lord on his return…. They crossed the river and climbed steeply northwards up to the village of Gazorkhan where directly ahead of them, firmly built on the outcrop of a great rock, stood the castle of Alamut, set proudly against the magnificent backdrop of the Hawdequan range. After a steep climb up the left-hand side of the rock, Mahdi and his escort rode through the imposing outer gateway of the castle, which overlooked a wide sweep of the valley … The governor and his deputy set off on a tour of inspection of the castle defences. To his surprise he found a number of new faces among the garrison and servants …

A sudden shaft of suspicion struck the governor’s mind: ‘Are you quite sure that these men are reliable,’ he asked, ‘and that they are not Ismailis connected with the accursed Hasan Sabbah? We must certainly have nothing to do with them. Before we know where we are, they will open the gates to him and seize the castle from us. I will not allow these people to play any tricks on us. Everyone knows that Alamut is the strongest fortresses in Daylaman and cannot be captured even by a thousand horsemen.’ …

The lord of Alamut had good reason to be fearful of Hasan Sabbah. But it was already too late. At the very time he was in Qazvin, Hasan was in fact hiding in another part of the town, finalising plans to take over his castle. Alamut was Hasan’s obvious choice as the base from which to launch his revolution. The valley below the castle was fertile and its inhabitants were mostly Shi’i Muslims, including many Ismailis on whom Hasan could count for support. The castle itself was easily defensible, as it was located on top of a massive rock and surrounded on all sides by mountains. Since it was built, the castle had never been taken by military force. Legend has it that the site of the castle was first indicated to a local ruler by an eagle that soared above the great rock, hence its name ‘Alamut’, the ‘Eagle’s Nest’….

In the summer of 1090, when Hasan received word from his agents that all was ready at Alamut, he set out from Qazvin with the greatest circumspection. He knew very well that the vizier Nezam al-Molk had issued orders for his arrest. As a result Hasan avoided the direct route from Qazvin to Andej, but took the longer route northwards through Ashkavar and arrived over the mountains, by the back door so to speak. Hasan stayed for a while in Andej in the guise of a schoolteacher called Dehkhoda. Soon he was joined by a band of his most loyal supporters, whom he sent in small groups to Alamut, ostensibly to seek employment. Some of these men probably settled in the village of Gazorkhan just below the castle, ready to be summoned at short notice.

Finally, Hasan himself entered the castle officially as a teacher to the children of the garrison. Once inside the walls, Hasan and his men befriended the soldiers and converted some of them secretly to their cause. Mahdi’s deputy himself was probably converted at some point and was waiting to help Hasan in his plan. The day arrived when Hasan was assured of significant support and minimum resistance from the garrison. He calmly went to Mahdi, revealed his true identity and announced that the castle was now in his possession. The governor was astounded at the so-called schoolmaster’s impertinence and summoned the guards to arrest him, only to find them ready to obey the upstart and put Mahdi to the sword at his command. At that moment the governor came to recognise the true nature of the plot against him and that he had been tricked. The castle was lost to him and he was powerless to do anything about it. In his victory, Hasan was magnanimous. He allowed Mahdi to leave unharmed and even gave him a draft for 3,000 gold dinars as the price of the castle. The draft was payable in the name of Ra’is Mozaffar, a Saljuq government official and secretly an Ismaili, who later honoured the payment in full, much to Mahdi’s astonishment. Within a generation, the Ismaili Imams succeeding Mawlana Nizar made their way to Alamut where they found safety from persecution.

Peter Wiley, The Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, (pp.16-23)

6. Imam Shams al-Din Muhammad

Imam Rukhn al-Din Khurshah was the final Imam to reign at Alamut, which fell to the Mongol emperor Hulegu Khan in 1256. In the year’s final months, the 26 year-old Imam at the fortress of Maymundez, assembled and consulted with his senior dais and advisors to decide whether or not to surrender or continue his resistance.

Earlier that year, the Mongols executed every adult male in Tun and also murdered every Ismaili envoy the Imam had sent to meet with Hulegu Khan. While deliberating, fighting continued unabated. The Mongols relentlessly battered down Ismaili defences, vowing to continue massacring Ismailis if the Imam did not surrender.

Ultimately, a group of Da‘is and advisers, led by the pre-eminent scholar and Da‘i Nasir al-Din Tusi, prevailed and the Imam agreed to surrender. As Ismailis dismantled their defences, the Imam appeared before Khan, defenceless, in the name of peace, and sacrificed himself to prevent further slaughter of his followers.

Escorting the Imam from one Ismaili fortress to another, Khan demanded surrender at the order of their Imam he held hostage. And so, one by one, Ismaili castles and fortresses were taken and destroyed. Ismailis were massacred and others sold as slaves. Finally, the Mongol horde set fire to Alamut, forever destroying nearly all of the Ismaili literary and intellectual treasures in its renowned library.

Once the surrender was complete and Khan had no further use for the Imam, he banished him to Mongolia while ordering the Imam’s family and servants, in Persia, excruciated. Then, when the Imam’s group rested for the night in the Khangay mountains of north-western Mongolia, Mawlana Rukn al-Din and his companions were led away, one by one, off the main road, and brutally murdered by their Mongol guards. In the words of Juwayni himself:

‘He and his followers were kicked to a pulp and then put to the sword, and of him and his stock no trace was left, and his kindred became but a tale on men’s lips and a tradition in the world.’

Nadia Eboo Jamal, Surviving the Mongols, (pp.47-49)

Although Mongol propagandist Juwayni loudly proclaimed that the Ismaili Imamat and all Ismailis had been destroyed in perhaps the most painful and horrific period of Ismaili history, it was not so.

Before the Imam was murdered, even before the surrender of the fortresses, Imam Rukhn al-Din Khurshah’s young son and successor, Mawlana Shams al-Din Muhammad (“the Sun of the Faith”) had, on the orders of his father, been concealed and secreted away to Azerbaijan by a small cadre of Ismaili Da‘i’s. So while the situation was dire, it was not hopeless. The Imam had ensured the Imamat’s continuity knowing, though hidden for the present, his successor would rise again. (Eboo Jamal, p. 51)

7. Nizari Quhistani

Ismaili history is punctuated with periods of concealment, dawr-i-satr, when the Imam’s identity and whereabouts are only known to a close circle of Ismaili Da‘is. To others, the Imam, donning a guise, appeared as a businessman or even embroiderer. However, though hidden, some enterprising Ismailis occasionally found him and experienced the didar they craved.

The Ismaili Da‘i Nizari Quhistani lovingly describes his didar in beautiful, mystical poetry that suggests the location or identity of the Imam without disclosing either. He describes a “handsome young man of exceptional spiritual authority with a large following in the city:”

Once someone stole my heart away.

There were others like me who had lost their hearts to him.

No one could get enough of him.

The feet of many were willing to walk on swords (for his sake).

His beauty was immeasurable and the marketplace was inflamed by him,

While he was always fleeing from the tumult of the common folk.Surviving the Mongols, (p.131)

Nizari then discovered that the Imam was to visit a “house of healing” — a common Sufi and Ismaili term for a place of worship. So, feigning illness, Nizari met the Imam whom he calls “the intoxicated one,” a common Sufi and Ismaili metaphor for the Imam.

The Imam “reprimand[ed] Nizari for coming all the way from Khurasan to meet him. He told the poet that the lover and the beloved are in reality never apart: ‘When was Qays ever without the face of Layla?’ he asked,” making reference to the Arabic analogue to Romeo and Juliet. (Eboo Jamal, Surviving the Mongols, p.132)

Nizari maintained taqiyya and never revealed the assumed identity of the Imam Shams al-Din Muhammad. His allusions to “madness” and “intoxication” are consistent with Sufi descriptions of spiritual love, and it was clear to close readers that — even in this time of extreme danger — Nizari indeed was granted the Imam’s didar.

8. Pir Pandiyat-i-Jawanmardi

In the Sathpanth tradition, the office of “Pir” is analogous to the Fatimid bab (“gate” of the Imam), a spiritual rank second only to the Imam himself. The station’s importance is illustrated by the fact that it is reserved for blood relations of the Imam, and is sometimes held by the Imam himself, as has been the case with recent Imams. Pirs are the “Spiritual Mothers” of the jamat just as Imams are their spiritual fathers. In his work Pandiyat-i-Jawanmardi, Imam Gharib Mirza explains that “the true believer must follow the Pir of his time, sincerely following him.”

On the death of Pir Hasan Kabir al-Din’s in India, his eighteen sons fought over his fortune and the dasond he collected on behalf of the Imam — with some of his children even absconding with portions of it. His younger brother, the Pir Taj al-Din, trekked to Persia, to obtain the Imam’s guidance and directions to resolve the matter. Although the Imam entrusted spiritual authority to Pir Taj al-Din, on his return to Uch, his nephews harassed him endlessly. Some even became Sunnis and tried to convince other Ismailis to do the same. Nevertheless, Pir Taj al-Din continued to lead the Uch and Lahori jamats, collecting their dasond and, eventually, delivering it the Imam in Persia.

The dasond included a special cloth for the Imam, whom, in characteristic generosity, gifted a small piece of it back to Pir Taj al-Din as a token of his recognition and blessings for his services. As an aside, oral traditions tell us the Imams sometimes issued a piece of cloth as proof the dasond was delivered to the Imam. When Pir Taj al-Din returned to the jamat, wearing his gift as a turban, the fractious South-Asian jamat turned on him, accusing him of stealing his beloved Imam’s dasond:

The shock of these accusations procured his early demise. Such was the uproar among his former disciples that they would not allow him to be buried in Uch, and it was only twenty years after his death that a proper mausoleum was constructed by his repentant followers.

Shafique Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, (p.125)

Meanwhile Sayyid Imamshah was dispatched to try and mitigate the damage caused by Pir Hasan Kabir al-Din’s children conversion to Sunni Islam and their attempts to sway as well. Unsuccessful and frustrated by those jamati members who did not heed his call to return to the faith, Imamshah went into seclusion and never re-emerged.

After the abuse that had been piled on Pir Taj al-Din and Imamshah, the Sindhi Ismaili community, not surprisingly, found themselves without a Pir and appealed to Imam Gharib Mirza to provide them with a new one:

Upon arrival [in Persia], they pleaded, ‘Our pir, Taj al-Din, has passed away. Now we are in need of a pir.’ The Imam then had the Counsels of Chivalry compiled and gave it to them saying, ‘This is your pir. Act according to its dictates.’

As such, the work is always respectfully addressed as Pir Pandiyat-i Jawanmardi, and this is the form the title takes in many of its manuscripts.

Shafique Virani, The Ismailis in the Middle Ages, (pp. 122, 125-126)

The Pandiyat-i-Jawanmardi, or Counsels of Chivalry, is a unique document in Ismaili history both for its content and its origin. Originally a compilation of pronouncements (farmans) of Imam Gharib Mirza given to the Persian jamat during Imam Abd al-Salaam’s lifetime, it later served a noble purpose after a period of conflict and chaos in the Indian Ismaili community.

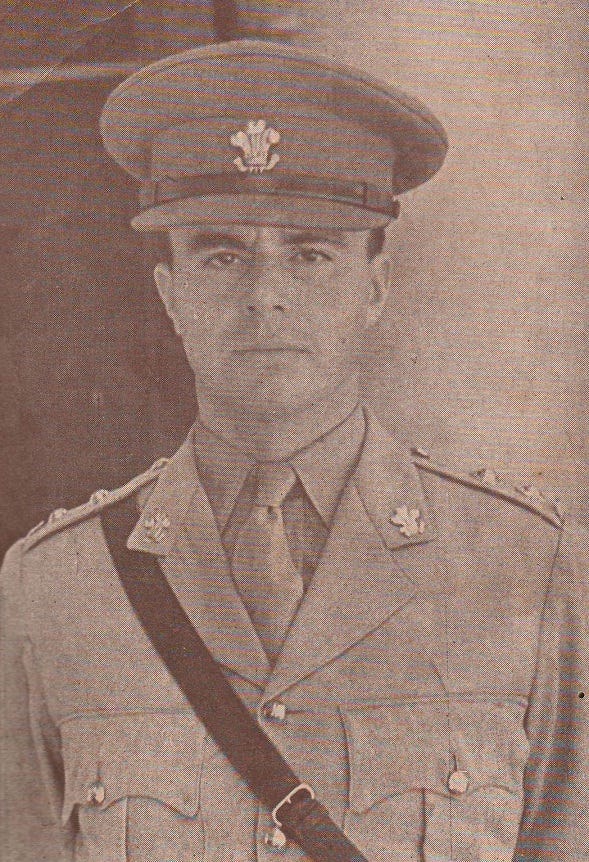

9. Prince Aly Salman Khan

Perhaps because he lived his life unconcerned about what would be said about him, Prince Aly Salman Khan is one of the most misunderstood and maligned figures in Ismaili history. Both the son of an Imam and father of an Imam, Prince Aly Khan was a devoted father and son — even supporting his son’s Imamat when some Ismaili jamats who, expecting his father to be the Imam, refused to follow the newly appointed Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni. A decorated and admired soldier in World War II, Prince Aly Khan was also a diplomat representing Pakistan at the UN, where he fiercely defended Islam in his speeches.

One remarkable story of his daring can be found in Willi Frischauer’s book, The Aga Khans:

During the period from August 15, 1944, until March 1945, frequently sent on missions to the front, he won the admiration of all by his bravery under fire and complete disregard of danger, by his intelligence, tact and character, and he was thus able to render the highest possible service to the allied army.’

Alerted by Aly, friends in several armies moving in on Germany were on the look-out for his and his father’s horses which the Nazis had taken from their French stables as loot. He was delighted to receive a message from U.S. General George Patton, whose storming finish had carried his troops farther east than any other, which said that the horses had been traced to the German National Stud at Altefelt but his troops were still some distance away. Because Soviet armies were fast approaching, no time was to be lost. With a jeep and a horse-trailer and a single G.I. to help him, Aly dashed across Germany but found the Germans still in control at Altefelt. It was a situation after his heart.

At the point of a gun he demanded the return of his horses. With Robert Muller who had gone into German captivity with the horses, he organised their removal, carting them two by two across the French border in an expedition which took five days and five nights.

Willi Frischauer, The Aga Khans, (p.149)

10. Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah

Hazrat Imam Shah Sultan Muhammad Shah lived at a seminal and transitional period in Ismaili history. Born when horse and carriage were the primary mode of transport, he lived through two world wars and, ultimately, led the unsophisticated, naive Ismaili jamat into the modern age.

More than just a religious figure, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah was one of the most illustrious global figures of his time. He was even elected as the President of the League of Nations (predecessor of today’s United Nations) — the first Muslim leader of the international body. As a visionary and a trailblazer, he was a founding father of Pakistan and of Aligarh University, India. However, prominence comes with great risk and this Imam was the target of an assassination attempt during World War I, which he describes in his memoirs:

Suddenly the British Government took urgent and alarmed cognizance of what subsequently became known, in Swiss legal history, as the affair of the Lucerne bomb. The German Secret Service did not believe that I was really ill. They thought, however, that their country’s cause would be well served were I put out of the way for good. They arranged to have a bomb thrown at me; and to make the operation certain of success they also arranged, with typical German thoroughness, to have my breakfast coffee poisoned. The bomb did not go off; I did not drink the coffee.

Aga Khan III, The Memoirs of the Aga Khan: World Enough and Time, (p. 109)

Bonus Story! Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni

Early in Mawlana Hazar Imam’s Imamat, on a visit to Count Akbarali’s Moloo’s residence in Nairobi, Hazar Imam asked the Count’s daughter, Yasmin Moloo, now Mrs. Yasmin Dhanani, a maths question. When she replied she found it difficult, Hazar Imam spent about 50 minutes explaining the solution. A copy of Hazar Imam’s notes and explanations appear below.

Credits

Header Image: Mohib Ebrahim (NanoWisdoms Archive)