Crucifixion of Jesus in Ismaili Thought and Spiritual Secrets Concerning Christ

Academic and Faith-Based Reflections on the Crucifixion and the Spiritual Reality of Jesus Christ the Messiah

“They killed him not, nor crucified him,

but so it was made to appear to them.”

- Holy Qur’an 4:157

Think not of those who are slain

in God’s way as dead. Nay, they live,

finding their sustenance

in the presence of their Lord.”

- Holy Qur’an 3:169

“…the conditions of the dialogue between Christianity and Islam change completely as soon as the interlocutor represents not legalistic Islam but this spiritual Islam, whether it be that of Sufism or of Shi‘ite gnosis.”

Henry Corbin, Spiritual Body and Celestial Earth, Prologue.

Khalil Andani, The Crucifixion in Shi‘a Isma‘ili Islam.

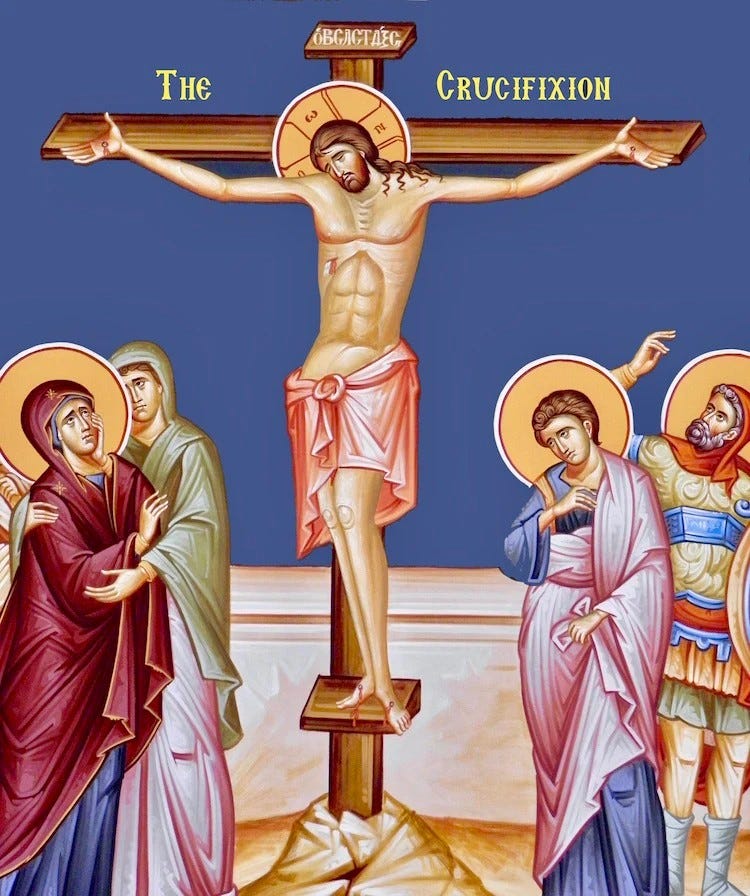

As observed by millions of Christians around the world, Good Friday marks the day when Jesus Christ was crucified. For Christians, this event is the climax of sacred history: the death of Christ on the Cross is believed to have redeemed and cleansed the sin of humanity. Indeed, the efficacy of the entire Christian doctrine – adhered to by the largest number of people in the world – depends upon the event of the Crucifixion. Interestingly, the faith of Islam, the second largest religion in the world after Christianity, seems to offer a completely different understanding of this event – it appears to deny the Crucifixion altogether. The only verse of the Holy Qur’an which speaks of the Crucifixion is the following:

wa-mā qatalūhu wa-mā salabūhu

wa-lākin shubbiha lahum

“They killed him not, nor crucified him,

but so it was made to appear to them.”

- Holy Qur’an 4:157

The Qur’anic denial of the crucifixion must be understood in its proper context: the Qur’an is only denying that the People of the Book crucified Jesus – and this appears to be in response to their boasting to have done so. A neutral reader may easily conclude that the Qur’an intends to say that the death of Jesus was ultimately due to God’s will and not the desires of those who may have actually killed him. One then wonders: how did the view that Jesus was not crucified take root in the Islamic world?

Interestingly, the earliest textual evidence stating that Muslims deny the historical event of the crucifixion is not actually Muslim at all - it comes from the writings of the Christian Church Father, St. John of Damascus.1 He made the statement to his Christian flock in the eight century, asserting that the Qur’an denied Christ’s crucifixion for his own polemical purposes of refuting the early success of Islam. While it is true that most Qur’ānic commentators came to deny the crucifixion of Jesus, this view is not actually rooted in the Qur’ānic verses but comes from commentaries which rely on other material from extra-biblical Judeo-Christian sources.2

The denial of the historical crucifixion was only one view among others on the subject to emerge from the Islamic world. There have been alternate interpretations of the same Qur’ānic verses which collectively offer a range of perspectives on the crucifixion – from total denial to actually asserting that the crucifixion did take place historically. Todd Lawson explains that:

John of Damascus’s interpretation of the Qur’anic account is, in fact, unjustifiable. The Qur’an itself only asserts that the Jews did not crucify Jesus. This is obviously different from saying that Jesus was not crucified. The point is that both John of Damascus and many Qur’an exegetes (Arabic mufassirūn), though not the Qur’an, deny the crucifixion. The Qur’anic exegesis of verse 4:157 is by no means uniform; the interpretations range from an outright denial of the crucifixion of Jesus to a simple affirmation of the historicity of the event.3

One of the schools of Islamic thought and philosophy which actually affirmed the historicity of the Crucifixion on a Qur’anic basis and, in fact, glorified it, is the tradition of Shi‘a Isma‘ili Islam. […] Over the centuries, the intellectual thinkers and philosophers of Isma‘ili Islam developed an elaborate metaphysics, philosophy, cosmology and esoteric exegesis (ta’wil) – including specific material concerning the life, spiritual function, and crucifixion of Jesus.

The Isma‘ili Muslim philosophers of the tenth and eleventh century were able to achieve a remarkable reconciliation and rapprochement between the Qur’anic and Christian views of the Crucifixion. While affirming the historicity of the event (in common with Christians), the Isma‘ili philosophers were still able to deny Christ’s death from a more spiritual perspective which they saw reflected in the Qur’anic verses. […] In fact, some of the Isma‘ili philosophers actually emphasized the importance of Christ’s death on the Cross from an esoteric perspective and saw in it an immense eschatological meaning. Finally, the Isma‘ili thinkers, relying on the method of ta’wil (esoteric exegesis), perceived great spiritual truths hidden in the symbolism of the Cross – the same truths which they saw symbolized in the words of the Islamic testimony of faith known as the Shahada.

This article explains the Isma‘ili Muslim understanding of the Qur’ānic verses on the Crucifixion, the meaning of the Crucifixion in Ismā‘īlī eschatology, and the esoteric exegesis (ta’wīl) of the Cross, as articulated by the medieval Ismā‘īlī thinkers. These Ismā‘īlī perspectives, due to their pluralistic, ecumenical and esoteric outlook, can play a great role in the modern age towards opening further doors of understanding and recognition between the faiths of Christianity and Islam.

The Isma‘ili View of the Crucifixion

“Think not of those who are slain in God’s way as dead. Nay, they live, finding their sustenance in the presence of their Lord.”

— Holy Qur’an 3:169

[…]

Several Isma‘ili philosophers of the tenth and eleventh centuries commented on the Crucifixion including the Ikhwan al-Safa, Ja’far ibn Mansur al-Yaman, Abu Hatim al-Razi, Abu Yaqub al-Sijistani and al-Mu’ayyad fi’l-Din al-Shirazi. All of them are in agreement in affirming the historicity of the Crucifixion, confirming that it was indeed Jesus himself who was crucified and not a substitute as maintained by many other Qur’anic commentators. For al-Mu’ayyad fi’l-Din al-Shirazi denying the historicity of the Crucifixion is to contradict a historical fact established by the testimony of two major religious communities, the Jews and the Christians. Even the prominent Sunni Muslim theologian al-Ghazali eventually came to affirm the Crucifixion, most likely learning this from the Isma‘ili sources.4

[…]

The Isma‘ilis thus affirm fully that Jesus died in the conventional sense — his physical body was crucified and killed. In fact, the Qur’an confirms in other verses that Jesus did actually die but that his death was ultimately due to the Will of God and not merely the desires of Jesus’ enemies:

Behold! God said: “O Jesus! I will cause you to die (mutawaffeeka) and raise thee to Myself and purify thee of those who disbelieve; I will make those who follow thee superior to those who reject faith, to the Day of Resurrection: Then shall ye all return unto me, and I will judge between you of the matters wherein ye dispute.”

- Holy Qur’an 3:55

“I said to them naught save as Thou didst command me: Serve God, my Lord and your Lord; and I was a witness of them so long as I was among them, but when Thou didst cause me to die (tawaffaytanee) Thou wast the Watcher over them. And Thou art Witness of all things.”

- Holy Qur’an 5:116-117

The Arabic words used above, mutawafeeka and tawaffaytanee, translated as God taking Jesus’ soul at death, occur throughout the Qur’an to describe the act of God or His Angels taking souls of people when they die.5 Thus, the Qur’an asserts that Jesus did actually die but attributes his death to God’s Will and not the agency of Jesus’ enemies.

[…]

Immediately, it may seem that affirming Jesus’ Crucifixion runs contradictory to the Qur’an’s denial: “They killed him not, nor crucified him, but it was made to appear to them” (4:157). One of the keys to understanding the Isma‘ili interpretation of this verse is the concept of nasut (human nature) and lahut (divine nature). For the esoteric schools of Islam such as Sufism and Isma‘ilism, the person of the Prophet or the Imam possesses two distinct natures or layers of being. The first is his human nature called the nasut and the second is his celestial or divine nature called the lahut. The divine nature (lahut) is the Universal Intellect (al-‘aql al-kull) which is also called the Light of Muhammad (nur Muhammad) or the Light of Imamat (nur al-imamah) and it is this Light (nur) which is manifested in the subtle soul of the Prophet or Imam. The nasut (human nature) of the Prophet or Imam is his physical body which is merely the ‘cover’ for the subtle soul and not the essence of his personality.6 […] With regard to these two natures being present in the Prophet Muhammad⁽ˢ⁾, the contemporary Islamic philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr writes:

The Prophet possessed eminently and in perfection both human (nasut) and spiritual (lahut) natures. Yet, there was never an incarnation of the lahut in the nasut, a perspective which Islam does not accept. The Prophet possessed these two natures and for this very reason his example makes possible the presence of a spiritual way in Islam.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Ideals and Realities of Islam (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1966), 90.

The nasut and the lahut remain as two distinct natures or layers of being; they do not intermix or mingle but exist in a union without confusion. Jesus, being one of the great Prophets of Islam, also possesses the same two natures. The Isma‘ilis were able to both confirm and deny Christ’s crucifixion in accordance with this duality: for it is only the physical body or the nasut of Jesus which was crucified on the Cross; the divine reality or lahut of Christ was unaffected and can never be subject to death. Christ’s subtle soul and the Light (nur) manifested through it could never be crucified. The Isma‘ili philosopher al-Mu’ayyad, in order to support the position that Christ could never die in reality, cites the following Qur’anic verse:

“Think not of those who are slain

in God’s way as dead. Nay, they live,

finding their sustenance

in the presence of their Lord.”

- Holy Qur’an 3:169

In a similar vein, an anonymous Isma‘ili text states:

The immaterial soul and the Sublime Temple of Light cannot be killed or crucified, nor even die. That which dies is only the ‘superficial covers’ of the body made of flesh and blood, which are nothing but an outward representation (mithal) of the immaterial Temple of Light.

Lawson, The Crucifixion, 21.

Thus, Jesus with respect to his pure soul and his essential reality — the Light (nur) of God – did not die in reality (‘ala haqiqah). The immutability and ineffability of the Light of God (nur Allah), manifested in the Prophets and the Imams, is conveyed in the following Qur’anic verse:

“They desire to put out the Light of Allah

with their mouths, and Allah will not consent

save to perfect His Light,

though the unbelievers are averse.”

- Holy Qur’an 9:32

[…] The Qur’an speaks of the lahut or divine nature of Christ when it refers to him as the Word (kalimah) and Spirit (ruh) of God7. All Christians and Muslims would readily agree that Christ could not be killed or crucified insofar as his true reality was God’s Word and Spirit. In this sense, some contemporary Muslim thinkers like Mahmoud Ayoub are in agreement with the overall Isma‘ili perspective:

The Qur'an is not here speaking about a man, righteous and wronged though he may be, but about the Word of God who was sent to earth and returned to God. Thus the denial of killing of Jesus is a denial of the power of men to vanquish and destroy the divine Word, which is for ever victorious.

Mahmoud Ayoub, The death of Jesus: Reality or Delusion, published in Muslim World (1980), 70: 91– 121.

[…]

The Isma‘ili position on the Crucifixion can be summarized as follows:

Historically, Jesus was crucified and killed; there was no ‘substitute’.

That which ‘appeared to them’ (shubbiha lahum) as being crucified was precisely the body or human nature (nasut) of Jesus.

Christ’s soul, as the manifestation of his divine nature (lahut), could not be killed and this is what the Qur’an speaks of when it says “they killed him not, nor did they crucify him”.

The Bible and the Qur’an are thus in agreement over the Crucifixion.

For more on this subject, including sections on “The Esoteric Significance of the Crucifixion”, “The Symbolism of the Cross”, and “The Cross of Light”, Click Here to Read the full article at The Matheson Trust: The Crucifixion in Shi‘a Isma‘ili Islam by Dr. Khalil Andani.

Related Content:

Video: Click Here to Watch a lecture on Isma‘ili Muslim Perspectives on Jesus.

“Hollow Worship”

It takes a lot of strength

to stick to your discipline.

It’s not automatic —

you have to put effort in.

Your body and mind may tell you:

you should do whatever feels good.

But did Jesus die on the cross

just for you to worship the wood?

Khayāl ‘Aly

December 25, 2017 (Original)

April 20, 2025 (Updated)

instagram.com/khayal.aly

instagram.com/ismaili.poetry

Poem Commentary:

This short poem speaks to the inner battle between spiritual discipline and earthly temptation. It opens with a clear acknowledgment that staying true to one’s higher path takes real strength — it’s not effortless or instinctive, but something that demands conscious, ongoing commitment.

The speaker recognizes the pull of the body and mind, which often urge us toward comfort, pleasure, or convenience. But this human tendency is challenged by a powerful rhetorical question: “Did Jesus die on the cross just for you to worship the wood?” This line jolts the reader into reflection, critiquing hollow or symbolic faith and urging a deeper engagement with the true meaning of Christ’s sacrifice.

Ultimately, the poem invites us to honor the cross not merely as a religious symbol, but as a call to live with purpose, effort, and moral integrity — to embody the teachings rather than simply revere them.

“Twice-Born”

I dare say: the physical body

is literally gross and opaque.

Compared to the spiritual body,

one may even say that it’s fake.

We should make use of our body,

but only as a temporal cover.

It helps to navigate this world

as we prepare to enter the other.

So don’t get over-attached

and idolize the physical form.

You took birth onto this Earth

but were always meant to be twice-born.

Khayāl ‘Aly

November 18, 2017 (Original)

April 20, 2025 (Updated)

instagram.com/khayal.aly

instagram.com/ismaili.poetry

Poem Commentary:

The poem above, “Twice-Born”, reflects on the distinction between the physical body and the spiritual self, suggesting that the material form is dense, limited, and ultimately impermanent. The speaker emphasizes that the body is merely a “temporal cover” — a tool for navigating earthly life, not something to overly identify with or idolize.

Rooted in a spiritual worldview, the poem encourages detachment from physical appearances and attachment, pointing toward the idea of being “twice-born” — a metaphor for spiritual awakening or rebirth. This echoes mystical traditions (both Eastern and Christian), where true life begins not with biological birth, but with the awakening of the soul to its divine origin and destiny.

Jesus answered and said unto him:

‘Verily, verily, I say unto thee,

Except a man be born again,

he cannot see the kingdom of God.’

— John 3:3, King James Bible

Is Jesus a Spirit or a Body? From ‘Allamah Hunzai’s Treasure of Knowledge (Part II)

Was Ḥazrat ‘Īsā [Jesus]⁽ᶜ⁾ raised to God in [this] elemental body (jism-i ‘unṣuri) or only as soul, has remained a very complicated problem for the people of wisdom. Let us find the correct solution to this important question in the light of the wisdom of Qur’ānic verses.

God says: “When the angels said: ‘O Maryam! Surely Allāh gives you glad tidings of a word from Him whose name is Messiah; ‘Īsā son of Maryam’” (Qur’ān 3:45).

The wisdom of this Qur’ānic verse shows that the real existence of Ḥazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾ was first determined and completed in the form of a sacred and living word which is also called a spirit. This speaking word and living spirit was cast in Maryam⁽ᶜ⁾’s ear as ism-i a‘ẓam which was later embodied in human attire. Eventually in the last moments of its life, it [i.e., the speaking word and the living spirit] left the body and became as pure (mujarrad [=disembodied, abstract]]) as it was earlier.

In this connection we should also reflect deeply about the reality of existence which is of two kinds: mental and external, or apparent and hidden, or spiritual and physical, or true and additional, or luminous and dark etc., etc. For instance, the soul of a human being is his luminous existence, and the body is his dark existence; and its physical example is a tree and its shadow. Our body, being our dark existence, certainly resembles our luminous existence to a limited extent, however, shadows cannot be completely identical to the things themselves. The shadow of a stone is not as solid and impenetrable as the stone itself; the shadow of a tree does not bear fruits; the shadow of a flower does not have any colour and fragrance, and the shadow of clouds does not shower rain.

The purport [of this discussion] is that the original things are different from their shadows. In the daytime, being attached to their original things, shadows have some light and some beauty as well, but when the fountainhead of light disappears, all these shadows are drowned in a dark sea and [thus] annihilated. This [dark] sea is the shadow of the earth which is called night. This same example is of a human body that until the light of soul is spread in it, its beauty and splendour exists, however, as soon as the soul departs, its value vanishes and its components mix with the elements according to the order: “kullu shay’in yarji‘u ilā aṣlihī” i.e., everything returns to its origin.

A blessed saying of almighty God regarding Hazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾ is: “And when Allāh said: ‘O ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾, I will take you away and cause you to ascend unto me and purify you of those who disbelieve’” (Qur’ān 3:55).

This sacred saying of Almighty God clearly and explicitly mentions Ḥazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾’s physical death and his spiritual ascension unto God. Moreover, when it is said: “They did not kill him nor did they crucify him” (Qur’ān 4:157), it means that Ḥazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾, rūḥu'llāh, was in the form of a pure spirit and a miraculous word. A spirit and a word can neither be killed nor crucified. Why does this truth confound us in spite of the Qur’ānic reality being very clear that:

“And reckon not those who are killed in Allāh’s way as dead; nay, they are alive (and) are provided sustenance from their Lord” (Qur’ān 3:169).

God’s command above clearly shows that from one aspect the martyrs are killed, but from another aspect [they are] alive. This means that the martyrs (shuhadā’) are physically killed in God’s path and spiritually are raised as living beings from this world to the hereafter. Thus it is evident that the word ‘qatal’ (to kill) is applicable [only] to the body and the word ‘zindah’ (alive) is applicable to the soul, as it is said in a ḥadīth: “A mu’min does not die but travels from this transitory world (dārul-fanā’) to the lasting abode (dārul-baqā’)”. Nonetheless, this ḥadīth does not mean that a mu’min does not die physically.

It is said in sūrah-yi Maryam (Qur’ān 19:17): “Then We sent to her Our Spirit, and he appeared to her exactly like a perfect man”.

Thus, if a spirit and an angel can completely take on and appear in a human form, a Perfect Man can also become a spirit and an angel by leaving the elemental body (jism-i ‘unṣuri). In this way, the principle that the only means of manifestation in the physical world is through a body and the spiritual world can only be reached through a spirit is established. Just like [that], Hazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾, whose celestial state was of a spirit and a pure word (kalimah), could not be manifested in [this] world without a body and similarly [he] could not be permanently sited in the heaven of spirituality without leaving the [physical] body.

Moreover, the wise Qur’ān mentions regarding Ḥazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾: “And we gave ‘Īsā, son of Maryam, clear miracles and strengthened him with the Holy Spirit” (Qur’ān 2:87, 2:253).

The above Divine farmān indicates the bestowal of two celestial things on Ḥazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾. The first is his miracles which were clear and explicit; the second is the Divine grace which he continued to acquire through the Holy Spirit hidden in his own personality. This is the reason the miracles are mentioned separately from the Divine help otherwise both of them would have been mentioned as one thing. Here, another important thing is that his physical miracles remained [with him] for a fixed period of time, however, Divine help — being a spiritual reality — was accessible to him even when he was leaving the elemental body, whereas the Jews thought that they were crucifying him.

Nonetheless, due to Divine help he did not have any fear, grievance or pain, and this is the meaning of God’s universal spiritual help. Such help means that in fact, Hazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾ lived on in the form of a pure spirit and a wisdom-filled word. Therefore, how could God’s spirit and word be afraid and disheartened by being killed or crucified! How could a miraculous personality whose life, existence, realisation and feeling are in the form of a sacred spirit and a pure word be killed or crucified?

God says: “And they did not kill him nor did they crucify him, but it appeared to them so and most surely those who differ therein are only in doubt about it, they have no knowledge respecting it, but only follow a conjecture, and they killed him not for sure. Nay! Allāh took him up to Himself” (Qur’ān 4:157-158).

These Divine farmāns show that according to God, Ḥazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾ was neither killed nor crucified, however, it appeared to the infidels as if they had succeeded in killing him by crucifying [him] and that he had not remained alive by any means. It means that God’s special servant cannot be spiritually crucified, especially Hazrat ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾, who had the great rank of God’s spirit (rūḥu'llāh). He was purely spiritual right from the start and as a perfect darwīsh he was corporeal only in name, his pure soul was raised from among the infidels by God as was His promise, and his blessed body, which was like a worn out attire of [his] soul, was given to the infidels so that they would be considered sinners according to the law.

Shubbiha lahum (i.e., “they are in doubt”, 4:157) implies that every person’s physical personality causes others to judge that he has merely the physical existence. Thus, the infidels, after having captured ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾’s body, thought that he was only a body. However, the real, spiritual and luminous ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾ was different and could never be crucified by those people. Thus, ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾ was a spirit both at the beginning and at the end, which is why it is said that they [i.e., the infidels] were in doubt. It is not in the sense that they had uncertainty [regarding crucifying ‘Īsā⁽ᶜ⁾’s body] but, according to Divine speech, it means that they thought that what they did to Isa⁽ᶜ⁾’s body, they had done the same to his soul [which was impossible].

‘Allāmah Naṣīr al-Dīn Naṣīr Hunzai, ‘Ilmī Khazānah (II), translated by Azeem Ali Lakhani as Treasure of Knowledge (Part 2), 22-25.

“With Exquisite Dignity”

I need to find a way

to access supernal energy,

so I can live my life

the way it was always meant to be.

If I’m open to receive

the Holy Spirit into me,

then I can live, think, and breathe

with exquisite dignity.

The human soul we are born with

can noetically be expanded.

We are meant to transcend death —

just like Jesus the ‘Son of Man’ did.

Khayāl ‘Aly

February 7, 2018 (Original)

April 20, 2025 (Updated)

instagram.com/khayal.aly

instagram.com/ismaili.poetry

Poem Commentary:

The poem “With Exquisite Dignity” explores a deep spiritual longing for transformation and divine connection. It expresses a desire to “access supernal energy”—a higher, heavenly power—in order to live a life aligned with divine purpose. By opening oneself to “receive the Holy Spirit”, one may hope to embody a life of “exquisite dignity”, suggesting a graceful, elevated way of being rooted in sacred awareness.

The poem continues by reflecting on the potential of the human soul—not as static, but as something that can “noetically be expanded”, or deepened through spiritual insight and inner knowing. The closing lines tie this potential to the figure of Jesus, the “Son of Man,” implying that, like him, we are meant to “transcend death”—not just physically, but in a metaphysical or eternal sense. Overall, the poem is a meditation on divine possibility, spiritual receptivity, and the transformative power of faith.

The Son of Man in The Bible

“Son of Man” is a deeply meaningful title that Jesus uses for Himself many times in the New Testament. It carries layers of humanity, divine authority, suffering, and eschatological (end-time) glory, and it also links back to Old Testament prophecy.

Here are some important biblical quotes about Jesus as the Son of Man:

“I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom…” (Daniel 7:13–14).

“For even the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45).

“You will see heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.” (John 1:51).

“No one has ascended into heaven except he who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up…” (John 3:13–14).

“For the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost.” (Luke 19:10).

The Son of Man in Ismaili Literature

In the cycle of ‘Īsā (Jesus), Mawlānā [i.e. the Imām] was called Ma‘add…. In his era there were many Deceivers. Jesus said: ‘I am the only son (pisar-i yigāna) of God.’ When the son is a man, it goes without saying that the father would also be a man.

He said: ‘I will return in the Qiyāmat [i.e. in the Time or Cycle of Resurrection] and divulge the Father’s task.’ He further said: ‘In the Qiyāmat I will command with the ruling of the Qiyāmat’ [i.e. at the level of the Ḥaqīqat (Esoteric Reality)]. Divulging ‘the Father’s task’ means introducing to mankind the Qā’im of the Qiyāmat [the Resurrector of the Resurrection].

The Christians say that whatever Jesus did partially in the cycle of the sharī‘at [Religious Law], such as reviving the dead, when he returns in the Qiyāmat [i.e. Cycle or Day of Resurrection], he will do it in a universal manner, that is, he will [spiritually] revive all mankind [to life] and establish the commandment of the Qiyāmat [i.e. the Ḥaqīqāt] fully, thus assisting the Father.

[S. J. Badakhchani: To ‘assist the Father’ means that Jesus will disclose the true meaning and implications of religious law as predestined by God.]

The Muslims also believe and say that Jesus will return in the era of the Qiyāmat, and he will rule truthfully among mankind for 40 years in such a manner that the wolf and the ram will drink water from the same spring, meaning the truthful (muḥiqq) and the adherents of falsehood (mubṭil). He will speak unambiguously and unite knowledge of the ẓāhir (exoteric) with [knowledge of] the bāṭin (esoteric).

Ḥasan-i Maḥmūd, Haft Bāb, translated by S.J. Badakhchani as Spiritual Resurrection in Shi‘i Islam: An Early Ismaili Treatise on the Doctrine of Qiyāmat (London: I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2017), 57.

“Raise My Vibration”

Lord, if it is true that I can raise my vibration,

please help me attain that blessed state of elevation.

If I can rise to that height, I think I can be free —

move past my dense body and reveal what’s underneath.

My physical form feels more like a metaphorical prison.

I long to follow the way of Christ, for indeed He is Risen.

Spiritual resurrection is a desideratum.

It is the gnostic path, since the time of Hazrat Adam.

Lord, I long to feel Your Breath fill my every atom,

and know the Truth that I could never ever fathom.

I pray I will find my way to the higher dimensions —

to live in a better world without lies and pretensions.

I get that I have to melt my stubborn ego away,

so that I can approach You, in a humble sort of way.

Lord, if it is true that I can raise my vibration,

please help me elevate to my final destination.

Khayāl ‘Aly

December 29, 2017 (Original)

April 20, 2025 (Updated)

instagram.com/khayal.aly

instagram.com/ismaili.poetry

Poem Commentary:

This poem, “Raise My Vibration”, is a heartfelt spiritual appeal, expressing the speaker’s deep longing to transcend the limitations of the physical self and align with divine truth. It begins and ends with a prayer to “raise my vibration,” framing the poem as both a meditation and a plea for transformation. The speaker yearns for elevation—a state of higher consciousness or spiritual freedom—through the indwelling of divine presence.

Throughout, the poem explores the contrast between the physical body, described as a “metaphorical prison,” and the soul’s latent potential for resurrection, modeled after Christ’s own. Gnostic and mystical themes surface in the references to “spiritual resurrection,” the ancient figure of Hazrat (or Prophet) Adam, and the rare term desideratum, suggesting a cherished spiritual ideal. The ego is acknowledged as a barrier to divine connection, and its dissolution is presented as necessary for humility and ascent.

Ultimately, the poem weaves together religious, esoteric, mystical, and universal spiritual imagery to portray the soul’s journey toward union with the divine—a path marked by surrender, devotion, and inner transformation.

A Question on the Crucifixion of Jesus⁽ᶜ⁾ from ‘Allamah Hunzai’s A Hundred Questions

Q25 Was Jesus⁽ᶜ⁾ crucified or not? (Proofs must be from the Qur’ān). Where did the light come from?

A25 I have an article regarding Jesus⁽ᶜ⁾ that is published in my Panj Maqālah II, please read it. It is our principle that if we have already answered a question, then we do not write on it again, and when necessary, we refer to it. However, we will try to discuss briefly some important points here too.

First of all, it should be noted that if God provides for His friends — the Prophets and Imāms — the means of fleeing from the battlefield instead of granting them the courage to have patience and endurance during the severest difficulties of the world and to sacrifice themselves for the sake of upholding the truth, then the enthusiasm for sacrifice and yearning for martyrdom will cease to exist, and nobody will be ready to suffer in the path of God. It is clear from this logic that the blessed body of Jesus⁽ᶜ⁾ was sacrificed for the sake of religion.

It should be known that God considers those martyrs, who are slain in the path of God as alive (3:169) and considers as dead some people who are as yet alive (16:21). Do such events not have two aspects? Does not this mean that martyrs are dead with respect to body but with respect to soul they are alive, and those who are considered dead by God are alive physically but are dead spiritually? Thus, it should be understood that Jesus⁽ᶜ⁾ was martyred physically on the cross, but spiritually he was alive in the presence of God. For he was the Spirit of God, and all the Prophets and Imāms are in the same position. Then who can harm the Spirit of God? This is the gist of the Qur’ānic verses regarding Jesus⁽ᶜ⁾. For further details see the article referred to above.

At the end of the question it is asked: “Where did light come from?” This question is conceived in the background that where the light exists today, it did not exist before. This idea indeed is not correct. The light is always in the same glory, as the Qur’ān (24:35) says: “Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth”.

If Allah is the light of the heavens and the earth (i.e. the universe and its existents), this means that the entire universe and all these things, which exist today, were immersed in the light of God in their luminous form in azal (timeless state), and then He gave them the material form.

This also means that the Universal Soul is a light, which comes into existence from the spiritual dissolution of the universe and the existents, and this fact is not outside the explanation of the abovementioned verse.

‘Allāmah Naṣīr al-Dīn Naṣīr Hunzai, Saw Su’āl, translated by Faquir Muhammad Hunzai and Rashida Noormohamed-Hunzai as Hundred Questions, 39-40.

“Verbal Inspiration”

The Messiah is the one

who makes all things new.

Internalize the Word —

it will resurrect you.

The Pure Word is the Spirit

that makes your soul rise higher.

The Lord breathes or speaks His Word

so that He may inspire —

those who are seeking

to live within the Holy Spirit.

Recite the Pure Word

and one day you may truly hear it.

Khayāl ‘Aly

May 23, 2018 (Original)

April 20, 2025 (Updated)

instagram.com/khayal.aly

instagram.com/ismaili.poetry

Poem Commentary:

This poem is a meditation on the transformative power of Christ and the Word of God. It begins with a declaration of the Messiah as the one who “makes all things new,” setting a tone of spiritual renewal. The speaker invites the reader to “internalize the Word”, which is equated with the Holy Spirit — a living force that elevates the soul.

Through poetic movement and repetition, the poem suggests that divine inspiration comes through the Word, spoken or breathed by the Lord. But it also requires receptivity: it’s those “who are seeking” that are invited into life with the Holy Spirit. The closing lines emphasize both recitation and revelation — pointing to a faith that is both spoken and heard, external and internal, ultimately culminating in a spiritual encounter with Truth.

And he that sat upon the throne said,

‘Behold, I make all things new.’ And he said unto me,

‘Write: for these words are true and faithful.’

—Revelation 21:5, King James Bible

Support Ismaili Gnosis in Publishing New Articles

Todd Lawson, The Crucifixion and the Qur’an: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought, (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2009), 7.

Ibid., 12.

Ibid., 12.

Ibid., 78

See Qur’an 4:97, 47:27, 6:61, 22:5, 2:234 for these occurrences.

For more on the concept of lahut and nasut in Isma‘ilism, see Sami N. Makarem, “The Philosophical Concept of the Imam in Ismailism”, Studia Islamica, Volume 27 (1967). See also Henry Corbin, Cyclical Times and Ismaili Gnosis, Tr. Ralph Manheim and James Morris, (London: Kegan Paul International in association with Islamic Publications Ltd., 1983).

One may oppose the idea that the Qur’an affirms the divine nature of Christ by referring to other verses where the divinity of the Son of Mary is outright rejected such as Qur’an 5:72 - “They are unbelievers (kafirun) who say, ‘God is the Messiah, the Son of Mary.” However, according to the esoteric exegesis of this verse provided by Ibn al- ‘Arabi, one of the greatest Sufi masters in Islamic history, the words ‘Son of Mary’ (ibn Maryam) refer specifically to the human nature (nasut) of Jesus and not his divine nature. Thus, the Qur’an is condemning only those who equated or confused Christ’s human nature (nasut) with his divine nature (lahut).