Proof of Prophecy: A Logical Argument for Muhammad’s Prophethood

This article continues from and assumes the conclusions of our previous article on the Proof of the Existence of God as Unconditioned Reality. We request readers not familiar with this argument and the concept of God as Unconditioned Reality to read it first before this article. We also recommend readers consult our earlier article 10 Surprising Facts to Know about the Qur’an, which is a companion article to this present piece.

“Nature is the great daily Book of God…

God’s miracles are the very law and order of nature.”Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(“What have we forgotten in Islam,” Letter to H.E. Dr. Zahid Husain, April 4, 1952)

“The Prophet himself never claimed any miracle of any sort. The only miracle which you have in Islam is the Qur’an.”

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,

(CBC Interview, “Man Alive with Roy Bonisteel”, October 8, 1986)

The purpose of this article is to offer a philosophical argument for the prophethood of Prophet Muhammad: to demonstrate that Muhammad b. ‘Abdullah (570-632) was a divinely-inspired prophet and guide appointed by God to convey divine guidance to humankind and that Muhammad’s speech – which includes the Qur’an – is an expression of that divine guidance. However, the implications of the argument should not be overstated: we are not claiming that Islam as it developed historically is the only true religion or that the Qur’an is God’s literal dictated speech or that those who do not recognize Muhammad as a prophet are condemned. On the contrary, a proper historical reading of the Qur’an actually shows that salvation is not the exclusive right of any single religious community, but rather, is based on recognizing God, responding to God’s blessings appropriately, and performing virtuous deeds. There are 1.5 billion Muslims of various denominations, branches, cultural divisions, political allegiances, and schools of thought – many of which are mutually contradictory. Therefore, Islam and Muslims cannot be viewed as a single homogenous mass. Perhaps the only belief shared by all Muslims is that God is one and Muhammad is His Prophet.

Acknowledgements: This argument, although original, is informed by the thought of the pre-modern Ismaili philosophers Abu Hatim al-Razi (d. 934), Nasir-i Khusraw (d. ca. 1088) and ‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), and the modern academic research of Navid Kermani (God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Quran, 2015).

A. Introduction: The Life and Career of Muhammad – A Very Brief Summary

Prophet Muhammad lived in the full light of history and his historical existence is well-documented by near-contemporary sources (listed here). The Text of the Qur’an as it exists today is believed by most historians of Islam to record the utterances of Muhammad made during his life time (the academic historical evidence is presented here).

Early Life

• Muhammad was born in Mecca to a holy family, the Banu Hashim, that traced its own lineage back to Ishmael (Isma‘il) son of Abraham. Muhammad was orphaned as an infant and was raised by his grandfather ‘Abd al-Muttalib and his uncle Abu Talib. Subsequently, Muhammad raised his uncle’s son, ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, as his own son.

• Seventh century Arabia was a tribal society, where allegiance to the tribe and clan trumped all else; there were no states, nations, borders, and no rule of law. Warfare and raiding was an everyday reality and quite ordinary. A state of war was the default relationship between neighboring tribes or cities unless a peace treaty was signed by the tribal leaders.

•Mecca was a commercial trade and aristocratic centre in Arabia and its prestige depended very much on its idolatrous materialistic culture centred on the sacred house of the Ka’bah.

•Muhammad became a successful merchant and was known throughout Mecca for his honesty and trustworthiness and his concern for the poor of society. In 595, his employer, Khadijah (who was 15 years older than him) proposed marriage to him and he accepted.

The Beginning of the Prophetic Mission

•Muhammad underwent a spiritual mystical experience during his regular night meditations in 610 and he believed that he was receiving divine inspirations and revelations from God, which he expressed through Arabic recitations, called “qur’an” (“recitation”).

•Muhammad began preaching his message as proclaimed in the Qur’an and his sermons: the oneness of God and the falsity of idol worship; the necessity of following and obeying God’s guidance through the guidance of Muhammad; the recognition of all prior divinely-inspired Prophets of the past such as Noah, Abraham, Moses, the prophets of Israel, and Jesus; explicit respect and recognition for all monotheistic faiths including Judaism and Christianity; the importance of spiritual purification and virtue; the continuous remembrance of God, the ethical imperative to eliminate injustice from society, the assistance of the needy and the vulnerable of society, and the final accountability of all humans on the Day of Judgment.

•Muhammad’s message attracted many followers in Mecca and aroused much opposition; many of his followers were collectively persecuted and many of them tortured.

•The melodious and rhythmic orality of the Qur’an was largely responsible for numerous people coming to have faith in and commitment to the message and divine inspiration of Muhammad. These Qur’anic recitations overpowered the Arabic poetry, rhyming speech, and discourse of his Meccan contemporaries who were masters in the speech arts. Several soothsayers and poets of Mecca challenged Muhammad in poetic disputation and were unsuccessful in imitating or rivalling or overpowering his qur’anic discourse.

•Muhammad was opposed by members of his own tribe, the Quraysh who were the commercial leaders and aristocrats of Mecca; for several years, Muhammad and his clan underwent social and economic boycott and blockade from the Meccans and almost died of starvation.

The Migration (hijrah) and the Early Community

•In 622, after Muhammad was nearly assassinated by a coalition of Meccan tribes and leaders, he and his followers fled to the city-state of Medina where Muhammad was invited to be the leader and arbiter between several conflicting tribes.

•Muhammad, his community, and a dozen or so Jewish tribes of Medina all signed the Constitution of Medina where they all swore to protect each other from outside attack and provide mutual support; this Constitution recognized the rights of all religious groups in Medina including Jews and Christians and counted all the Jewish tribes as part of the community or Ummah of Muhammad.

•The early community (ummah) of Muhammad was inter-confessional and ecumenical: it included Believers (those who believed in Muhammad’s prophethood), Jews, and Christians – who were to practice and follow their own religious traditions. Two Qur’an verses (2:62, 5:69) explicitly recognize that Jews and Christians and all those who worship God sincerely and work virtuous deeds will attain salvation.

Shari‘ah, Women’s Rights and Marriages

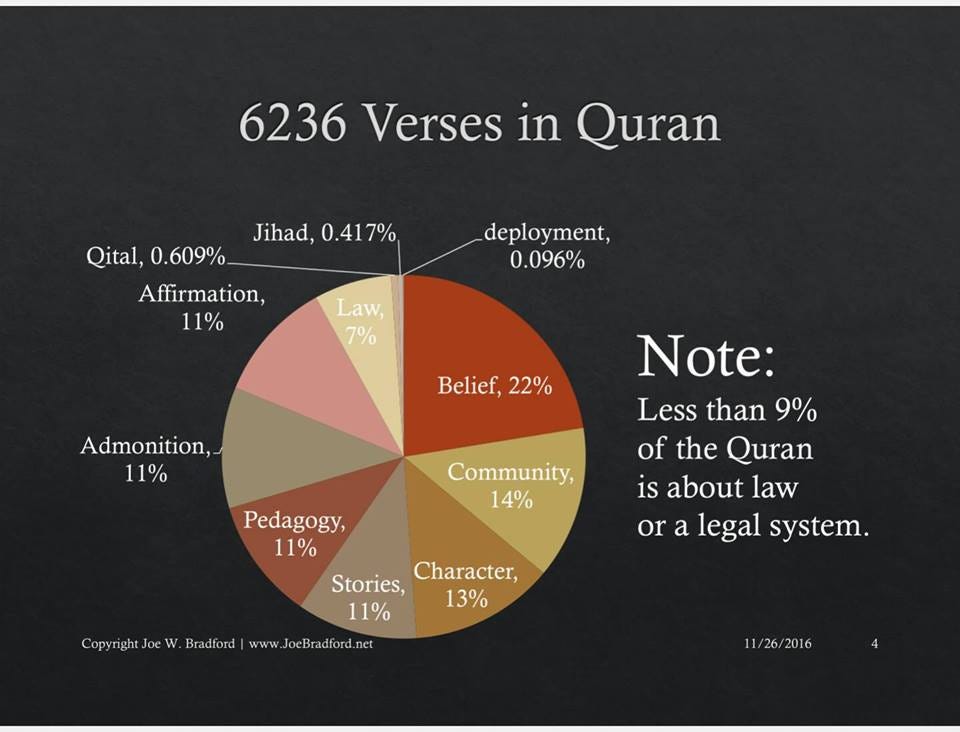

•There is no Shari‘ah in the Qur’an – Shari‘ah is a set of legal interpretations created by Muslim jurists centuries after Muhammad. In the context of the state of Medina, the Qur’an contains at most 500 verses on legal matters (marriage, divorce, writing wills, business transactions, debts, estates, etc.) out of over 6,000 verses.

•Women in 7th century Arabia before the advent of Islam had little in the way of rights and were not considered persons. Muhammad and the Qur’an (2:228, 4:19, 4:1, 33:35), explicitly recognized the spiritual equality of men and women as persons under God (in contrast to the literal teachings of Confucius and the Bible).

•The Qur’an outlawed female infanticide, granted women the right to property (4:7), the right to inheritance (4:11), the right to consensual marriage, the right to divorce (4:35), the right to retain her own property after marriage (4:11), the right to be witnesses (2:282), the right to work, etc. (In contrast, Western Europe only started granting women rights to property and personhood in the 18th century; America and British Commonwealth recognized women as persons with equal rights in the 19th-20th century.)

At the time Islam began, the conditions of women were terrible – they had no right to own property, were supposed to be the property of the man, and if the man died everything went to his sons. Muhammad improved things quite a lot. By instituting rights of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce, he gave women certain basic safeguards. Set in such historical context the Prophet can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women’s rights.

Professor W. Montgomery Watt (Christian Reverend, Orientialist Historian of Islam, d. 2006),

(Interview with Alstair McIntosh, 1991, Read Online)

•Prophet Muhammad married 12 women over his lifetime: 1 marriage was for love (Khadijah); 6 marriages (Sawda, Hafsah, Zaynab, Umm Salamah, Umm Habibah, Maymunah) were to vulnerable widowed and divorced women whom Muhammad took into his house and protection; 2 marriages were proposed or requested by the women (Safiyyah, Zaynab); 2 marriages were to form familial and political alliances with another tribe (A’isha, Juwariyah); 1 marriage (Maryam the Copt) was to a slave girl sent to Muhammad by the Archbishop of Alexandria (more on Muhammad’s marriages here).

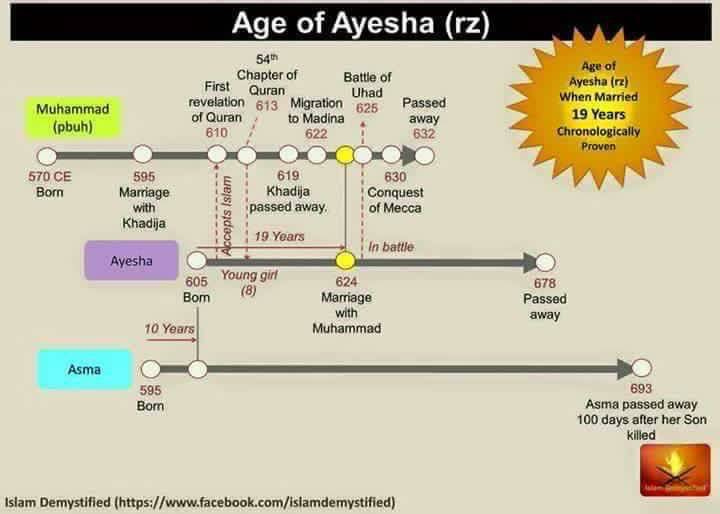

•Contrary to popular myth, A’isha was not six years old when she married Muhammad. All of the historical evidence when examined as a whole suggests that A’isha was born 4 years before Muhammad began his prophetic mission and was married to the Prophet on her father’s initiative in the tenth year of Muhammad’s mission – she was therefore around 14 years of age at the time and this was a normal marriage age until quite recently (all the evidence is analyzed in this peer reviewed article). Ismaili Gnosis has summarized the evidence from various Muslim historical sources and reports which shows that she was 18 years old at marriage.

The Battles with the Meccans

•The Meccans launched several attacks on Muhammad’s community in Medina in which the Meccan forces greatly outnumbered Muhammad’s defenses: the Battle of Badr (624), Battle of Uhud (625), Battle of Khandaq (627). Muhammad’s community won Badr, lost Uhud, and outlasted a Meccan siege in the the Battle of the Khandaq (Trench).

•During the years of these battles, two Jewish tribes of Medina collaborated with the Meccan, violated their oaths, and committed treason against Muhammad’s community of Medina: the Banu Nadir and the Banu Qurayza.

•The Banu Nadir tried to assassinate Muhammad at least twice; after their plot failed they were expelled from Medina.

•The Banu Qurayza secretly allied with the Meccans during the Battle of the Trench and later attacked Muhammad’s community using military force. The defeated Banu Qurayza voluntarily submitted to the judgment of a former Jew who passed judgment accordance with Old Testament law – their male combatants were executed and the rest of the tribe was expelled from Medina (read more here).

•In 628, several Jewish tribes including the Banu Nadir, Banu Qurayza and others gathered at Khaybar to form an alliance and attack Medina. Muhammad’s forces defeated them at Khaybar and he allowed the defeated Jewish tribes to live in peace, practice their religion, and have protection from Muhammad’s army as long as they paid tribute. Read more on the context and circumstances of each major battle here.

Final Years

•In 628, Muhammad signed a 10-year peace treaty – the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah – with the Meccans which allowed his community to move freely around Arabia. Within one year, the Meccans violated the peace treaty when they killed some of Muhammad’s followers. More detail on the Qur’anic verses about warfare revealed during this time here.

•In 630, after the termination of the Peace Treaty, Muhammad’s position in Medina had grew due to various Arabian tribes allying with him and converting to Islam. With a force of 10,000 men, Muhammad marched on Mecca and entered the city with little bloodshed. Muhammad granted amnesty and security to the Quraysh and their leader, Abu Sufiyan, who had violently opposed Muhammad for the last decade.

•In 632, Muhammad performed his final pilgrimage to Mecca, declared his cousin and son-in-law, Imam ‘Ali b. Abi Talib as his political and spiritual successor and passed away shortly after.

B. The Argument for the Prophethood of Muhammad

Step 1: Premises and Definitions: The Speech of God and the Book of God

The argument relies on the below premises (proven in the prior article on the existence of God):

In all of reality, there is one Absolute, Simple, Unrestricted, Eternal, Unconditioned Reality – a reality whose existence depends on nothing else – this is called “God”;

Other than God, everything else in reality is a Conditioned Reality – a reality whose existence at any given time depends on another reality;

All conditioned realities ultimately depend upon God qua Unconditioned Reality for their existence at all times;

In other words, God qua Unconditioned Reality creates and sustains the existence of all conditioned realities – this is the philosophical meaning of God being the “Creator” of all created beings.

In current parlance, Muslims refer to the Qur’an and prior scriptures as the Speech or Word of God and the Book of God, just as Christians and Jews refer to the Bible as the Word of God. The common person’s understanding is that God literally “spoke” the Qur’an in Arabic or the Torah in Hebrew and that this Qur’an/Torah was first inscribed as a “heavenly book” before it was revealed or sent down to the earth. However, in Shia Ismaili Islam, the meaning of God’s Speech and God’s Book differ from this popular common understanding, as explained below.

First Definition: The “Speech of God” is God’s Creative Act that originates, sustains, and nourishes all conditioned realities

The creation according to Islam is not a unique act in a given time but a perpetual and constant event; and God supports and sustains all existence at every moment by His Will and His Thought. Outside His Will, outside His Thought, all is nothing, even the things which seem to us absolutely self-evident such as space and time. Allah alone wishes: the Universe exists; and all manifestations are as a witness of the Divine Will.”

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan: World Enough and Time)

A. God’s “speech” or “word” is not in the form of sounds, words, or letters – because God is absolutely simple and transcends time, space and matter whereas audible speech (sounds, letters) come through the intermediary of bodies and air.

B. In human terms, “speech” is an action of the speaker by which he expresses a particular intention, message, meaning, or command.

C. By analogy, “God’s Speech” is His single eternal act of creation bestowing existence upon all conditioned realities at every moment.

D. Therefore, “God’s Speech” in reality is His creative act of originating and maintaining all conditioned realities.

The Creator (the unique, absolutely simple, unrestricted, unconditioned Reality itself) must be a continuous Creator (source of the ultimate fulfillment of conditions) of all else that is real at every moment it could cease to be real (i.e. at every moment of reality). Analogously speaking, if the Creator stopped “thinking” about us, we would literally lapse into nothingness.

Robert Spitzer, (New Proofs for the Existence of God, 143)

Second Definition: The “Book of God” is the entirety of Conditioned Realities sustained by and manifesting the “Speech of God”

Nature is the great daily Book of God whose secrets must be found and used for the well being of humanity. Islam is essentially a natural religion, the miracles quoted in the Qur’an are the great phenomena surrounding us and we are often told that all these manifestations can be used and should be, with intelligence, for the service of man.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(Message on Radio Pakistan, Feburary 19, 1950, Read on NanoWisdoms)

A. “God’s Book” is not in the form of written words, letters and language – because God transcends both time, space, and matter whereas written words/letters/language only exist by means of physical bodies, space, and time.

B. In human terms, “writing” is the transcription or manifestation of speech and is posterior to speech.

C. By analogy, God’s “writing” or “book” is the entirety of conditioned realities (created beings) which receive, manifest, reflect or inscribe “God’s Speech” (God’s creative act).

D. “God’s Book” in reality is the entirety of conditioned realities and their intelligible forms.

In conclusion, “God’s Speech” (the eternal creative act of God) continuously creates, sustains, and expresses itself in the form of “God’s Book” (the conditioned realities or created beings).

Summary of Premises and Definitions:

God qua the Absolute, Simple, Unrestricted, Unconditioned Reality exists (from prior article).

God’s Speech refers to God’s eternal creative act that continually creates and sustains all conditioned realities (from above).

God’s Book refers to the entire ensemble of conditioned realities or created beings (from above).

Human beings possess a unique faculty of cognition (called intellect) – that other animal species do not possess – by which humans intellectually discern and rationally express knowledge through discursive speech and writing.

The Demonstration of Divine Guidance and the Necessity of the Guide

Step 2: “God’s Speech” (His creative act) bestows divine guidance upon all conditioned realities (“God’s Book”) for their wellbeing.

Islam is fundamentally a natural religion. All its dogmas and doctrines of whatever sect or school, are ultimately based on the regularity and order of natural phenomena.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(“This I have learned from life,” February 4, 1954, Read at NanoWisdoms)

A. All observable things in the Universe, whether nonliving or living, display regular predictable and rational behavior – this behavior is called the “laws of nature” in modern scientific terms.

B. The laws of nature are not the causes of this regular behavior, they are merely propositional descriptions for this behavior; the regular behavior of all matter still requires explanation and a cause. Einstein himself once wrote that “a priori one should expect a chaotic world, which could in no way be grasped by thought.” (Einstein and the Generations of Science, 1982, xviii)

C. If God continuously creates and sustains everything in the Universe, the rational, orderly, regular behavior of the Universe occurs due to divine guidance – meaning that God’s creative act (“God’s Speech”) continuously guides and directs all the objects of the Universe to behave regularly for the fulfilment or completion of some disposition, power, or tendency.

A struck match generates fire and heat rather than frost and cold; an acorn always grows into an oak rather than a rosebush or a dog; the moon goes around the earth in a smooth elliptical orbit rather than zigzagging erratically; the heart pumps blood continuously and doesn’t stop and start several times a day; condensation results in precipitation which results in collection which results in evaporation which in turn results in condensation; and so forth. In each of these cases and in countless others we have regularities that point to ends or goals, usually totally unconscious, which are just built into nature and can be known through observation to be there whether or not it ever occurs to anyone to ask how they got there… it is impossible for anything to be directed towards an end unless that end exists in an intellect which directs the thing in question towards it. It follows that the system of ends or final causes that make up the physical universe can only exist at all if there is a supreme intelligence or intellect outside the universe which directs things towards their ends. Moreover, this intellect must exist here and now, and not merely at some beginning point in the past, because causes are here and now, and at any point at which they exist at all, directed towards certain ends.

Edward Feser, (Aquinas: A Beginner’s Guide, Chapter 3)

By God’s guidance I understand the fixed and immutable order of nature, or the connection of natural things. For we have said above, and have already shown elsewhere, that the universal laws of nature, according to which all things happen and are determined, are nothing but the eternal decrees of God, which always involve eternal truth and necessity. Therefore, whether we say that all things happen according to the laws of nature, or that they are ordered according to the decree and guidance of God, we say the same thing.

Baruch Spinoza, (Daniel Garber, “God, Laws, and the Order of Nature: Decartes and Leibniz, Hobbes and Spinoza,” in The Divine Order, the Human Order and the Order of Nature, ed. Eric Watkins, 63)

D. The laws of nature are the manifestation of divine guidance, some examples of which are:

The Universe and everything within it from quarks, subatomic particles, atoms, molecules, bodily masses, etc. behave according to regularities and patterns known as the laws of physics, whereby each kind of material object moves toward the fulfilment or completion of some disposition, power, or tendency – this is divine guidance for inorganic beings.

Living things (from single celled organisms to animals) are able to find and derive nutrition from their external environment, adopt accordingly, and preserve their own existence and species due to the specific capacities that God’s Speech bestows upon them – this is divine guidance given to organic living beings.

The human intellect, which recognizes first principles and operates through the laws of logic in order to reason from premises to conclusions, is a special capacity bestowed by God’s Speech – this is divine guidance given to all human beings. These natural laws of the Universe and intellectual laws of the human intellect together also provide guidance to human beings for both their survival and flourishing. (Meanwhile, anyone who claims that there is no divine guidance within the Cosmos whatsoever can only be correct if he or she claims absolute omniscience over the Universe).

E. Therefore, “God’s Speech” (the creative act of God) manifests throughout the Cosmos (“God’s Book”) through specific divine guidance appropriate to each level and species of conditioned reality.

God has a general guidance penetrating all existents in proportion to their circumstances and their natures – and specifically in animals, for every animal is specified by being guided to whatever is beneficial for its existence and its survival, by seeking the protection of the species of it and the individual of it – that being through nature and innate predisposition, not through instruction and thinking. More specific than that is the guidance of humanity, for it is specified by being guided to whatever is beneficial for its existence and its survival, by seeking the protection of the species of it and the individual of it and seeking the benefit of other than its own species – that indeed being through instruction and thinking.

‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani, (Keys to the Arcana, tr. Toby Mayer, 179)

Step 3: At least one human being at any given time fully comprehends the totality of the divine guidance that God’s Speech conveys for human beings

All Islamic schools of thought accept it as a fundamental principle that for centuries, for thousands of years before the advent of Muhammad, there arose from time to time messengers, illumined by Divine Grace, for and among those races of the earth which had sufficiently advanced intellectually to comprehend such a message. Thus Abraham, Moses, Jesus and all the Prophets of Israel are universally accepted by Islam. Muslims indeed know no limitation merely to the Prophets of Israel; they are ready to admit that there were similar Divinely inspired messengers in other countries — Gautama Buddha, Shri Krishna and Shri Ram in India, Socrates in Greece, the wise men of China, and many other sages and saints among peoples and civilisations, trace of which we have lost. Thus man’s soul has never been left without a specially inspired messenger from the Soul that sustains, embraces and is the universe.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan: Islam – The Religion of My Ancestors, Read at NanoWisdoms)

A. If God’s Speech (His creative act) continuously provides divine guidance for human wellbeing, then at least one human being in every time-period of human history fully comprehends the totality of this divine guidance.

Support: If this is not the case and the divine guidance is only known partially, then there is some portion of the divine guidance that remains unknown to humanity at a given time. This guidance would be inaccessible to human beings in principle. However, guidance only fufills its function and serves as “guidance” when it is actually accessible to and guiding the recipients it is meant to guide; inaccessible guidance by definition is not guidance in actuality. Thus, any divine guidance for human wellbeing must be known in its entirety and fully recognized by at least one human being at every moment that there are human beings.

B. The human being who fully comprehends this divine guidance is distinguished from other human beings who do not fully comprehend the totality of the divine guidance – due to possessing a superior faculty of cognition or perception;

Support: By logical necessity, there must be a factor to account for why a certain human being fully comprehends the totality of divine guidance that issues from God’s Speech and other human beings do not. This property must be internal and specific to that human being and pertain to his faculties of knowledge and perception. By analogy, the human species is distinguished from all other animal species through possessing a special faculty of cognition, the intellect, by which humans utter articulate speech (i.e. language) and produce writing to the exclusion of animals.

C. Thus, there is always at least one human being in the world at any given time who fully comprehends the totality of divine guidance by means of a superior cognitive faculty that other humans do not possess. This human being who comprehends the totality of divine guidance is called the “Possessor of Divine Guidance.”

Explanation: By analogy, the Possessor of Divine Guidance, by means of his superior faculty of cognition, “reads” God’s Book (the entirety of conditioned realities) and thereby comprehends the totality of divine guidance that emanates from God’s Speech – in the same way that only the human species amongst all animal species ca “read” rational speech in the form of writing. This is the real meaning of the Qur’anic or Biblical idea that “God’s Book” is revealed to a messenger or a prophet through the Holy Spirit: the Spirit refers to this higher faculty of cognition of the Possessor of Divine Guidance and the “Book of God” refers to the divine guidance present in conditioned realities.

“And that We have inspired you [Muhammad] with a Spirit (ruh) from Our Command. You did not know what was the Book (al-kitab) and what was the Faith. But We have made it a Light (nur) by which We guide such of our Servants as We will. And verily, you guide to a Straight Path.”

Holy Qur’an 42:52

“The Creator of the world is like the “writer,” the world and everything within it is His Book, and His Messenger is the “reader” of this Book…The spirit of the Messenger is a spirit that is higher than the human soul, by which the Messenger is distinguished. This is in the same way that human beings are distinguished amongst all the animals by means of a spirit higher than theirs. Thus, the Messenger who is the “reader” of the Book of God is the closest person to God, just as every reader among human beings is close to the writer in terms of recognition, and others who are unable to read writing are further away from the writer in similar terms, and they cannot perceive the speech of that writer except from the speech of that reader. In the same way for the Messenger of God, who reads the Book of God, possesses a superiority over all the people who are unable to read it, which is [also the case] for those who read human writing over those who do not read.”

Sayyidna Nasir-i Khusraw, (Zad al-Musafir, 219)

The Qualities of the Possessor of Divine Guidance

Step 4: The Possessor of Divine Guidance in every time period communicates this divine guidance to other human beings through speech.

A. Human beings only have access to the divine guidance if the Possessor of Divine Guidance communicates it to them.

B. By logical necessity, the Possessor of Divine Guidance must actually communicate this divine guidance to them.

C. Speech is superior and prior to writing.

Support: This is because human beings communicate knowledge and meaning to other human beings through speech or writing. However, writing is merely the transcription of speech in visual form. Written communication can be subject to textual corruption (through errors in preservation) and intellectual corruption (through willful or erroneous misinterpretation), whereas communication through speech is more fluid, more present, and can be clarified immediately in the case of error on the receiver’s part. Writing is static and fixed and becomes oudated whereas speech is dynamic and responsive to each new situation that requires divine guidance. Therefore, speech is logically and historically prior to writing and represents the most immediate and original expression of what is being communicated.

D. Therefore, the Possessor of Divine Guidance in every time period communicates divine guidance to other human beings through speech. This is the meaning of the Qur’anic expression of “reciting the Book of God” or “reciting the Word of God”: the Possessor of Divine Guidance perceives or “reads” the Book of God, recognizes within it the divine guidance from God’s Speech (God’s creative act), and then communicates or “recites” this divine guidance to other human beings:

And recite, [O Muhammad], what has been inspired to you of the Book of your Lord. There is no changing of His Words, and never will you find in other than Him a refuge.

Holy Qur’an 18:27

Step 5: The Possessor of Divine Guidance in every time-period is recognizable to other human beings through one of two external signs – designation by another Possessor of Divine Guidance or inimitable speech.

A. It must be possible for humans in every time period to recognize a Possessor of Divine Guidance so that they may obtain the divine guidance from him.

B. The Possessor of Divine Guidance in any time-period must claim to be the Possessor of Divine Guidance and display external signs by which others can recognize him.

first external sign: that Possessor of Divine Guidance is identified and designated and appointed by another Possessor of Divine Guidance. This is occurs recursively from one’s recognition of a prior Possessor of Divine Guidance.

second external sign: that the speech of the Possessor of Divine Guidance, by which he conveys divine guidance, is inimitable, unmatchable and absolutely unique compared to the speech of other human beings who are not Possessors of Divine Guidance.

For example, the articulate rational speech of human beings – who possess intellect and reason – is clearly distinguished from the sounds and gestures made by animals who do not possess intellect and reason. In the same way, the inimitable speech of the Possessor of Divine Guidance will surpass and transcend the rational speech of ordinary human beings (who do not possess that divine guidance).

No animal has the ability to receive what is in the mind of another by the medium of rational speech, or to render it to another in that way… Since rational speech (nutq) is general to two meanings: the first of them is thinking and discerning, and the second is the declaration of what is thought and discerned; and furthermore, “rational speakers” (natiqun) are according to a hierarchy and an inequality in regard to [the meanings of nutq] as a whole, this hierarchy culminates in ascension to the rank of independence from discursive thinking in the category of ‘discerning’, such that the unseen becomes for him openly seen and what arises for someone else through discursive thinking arises for him through innate nature. It is the same in the category of ‘declaration’, so that all of his speech becomes inspired revelation (wahy) and what arises for someone else through authoritative instruction, arises for him through intuition. Thus his speech is distinguished as a whole, in these two ways (discernment and declaration), from the speech of other speakers, in perfection and nobility; and just as speech comes to be the inimitable miracle of the human being over the animal, likewise that perfection in respect of it comes to be the inimitable miracle of the prophet over human beings.”

‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani, (Keys to the Arcana, tr. Mayer, 120-21)

C. Therefore, the Possessor of Divine Guidance in any time-period will either:

a) be designated and appointed by another Possessor of Guidance; and/or

b) will communicate the divine guidance through inimitable speech that surpasses ordinary human speech.

Step 6: Prophet Muhammad was the Possessor of Divine Guidance in his time-period (610-632 AD).

In the seventh century of the Christian era there was a rapid and brilliant new flowering of humanity’s capacity and desire for adventure and discovery in the realms of both spirit and intellect. That flowering began in Arabia; its origin and impetus were given to it by my Holy ancestor, the Prophet Muhammad, and we know it by the name of Islam.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan: Islam – The Religion of My Ancestors, Read at NanoWisdoms)

A. Prophet Muhammad, a historical figure who lived from 570-632 AD, claimed to be the divinely-inspired Possessor of Divine Guidance when he declared that he was a Prophet and Messenger of God who guides people to the right path (see historical documentation that Prophet Muhammad existed in history; see what the Qur’an claims about Prophet Muhammad; see summary timeline of Prophet Muhammad’s prophetic career above).

B. As a visible sign of his claim to receive divine inspiration and convey divine guidance, Muhammad spoke and uttered Qur’an – divinely-inspired recitations spoken in God’s name over 23 years in a variety of contexts, situations, and events (see historical documentation that the contents of the compiled Qur’an Text date to the mid-7th century).

If one believes in Muhammad as a prophet, it is not far-fetched to point to the originality of his language as evidence of his divine mission. If one sees in as an artist, one is at least tempted to infer from the unprecedented character of his work that he was a genius… In the history of literature, the only literary provocations that have made a lasting mark are those that contributed to a change in the norm: those that did not simply place themselves outside the existing horizon of expectations, but engendered a new horizon. By that standard, the Quran can be considered to surpass all the literary works of Arabic culture.

Navid Kermani (German Scholar of Islam, Novelist)

(God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 82)

C. The Qur’an’s literary form is inimitable and miraculous compared to all other forms of Arabic speech – as testified to and affirmed by numerous Orientalist and Western scholars of Arabic literature, the subjective experience of the Qur’an by Muhammad’s contemporaries and Muslim communities over the centuries, and the unanimous scholarly opinion of Muslim theologians, philosophers, and grammarians.

Supporting Explanation: By the terms – miracle/miraculous or inimitability/inimitable (i‘jaz) – we do not mean a “break in the laws of nature” or a “divine intervention” in the ordinary course of events. As already explained, God creates and sustains all existence at every moment – so divine “interventions” are wholly unnecessary: the laws of nature are never broken because they are the manifestation of God’s continuous creation and guidance in the Universe. When we say that a certain production is “inimitable” or “miraculous”, we mean that such a production transcends the capacities of a certain class or species and is beyond the productive capabilities of that species. Thus, a production is only inimitable or miraculous in relation to some standard or capacity. For example, human rational discourse and its various products like science, poetry, art, abstract thought, etc. are certainly “inimitable” and “miraculous” with respect to the animal species. In the same way, when we say that the Qur’an is inimitable and miraculous with respect to human beings, this means that the literary form (nazm) of the Qur’an together with its meaning is a speech or discourse that transcends the productive capacity of human beings who are not divinely-inspired prophets. The fact that the Qur’an is inimitable constitutes the greatest proof that Prophet Muhammad was the Possessor of Divine Guidance in his lifetime and a divinely-inspired Prophet.

Just as the movements of a human being come to be the inimitable miracles for an animal, namely the human being’s movements pertaining to thought, speech and action, likewise the movements of the Prophets come to be the inimitable miracles for the human being, namely their movements pertaining to the innate predisposition, to revelation and character – for they are those whom God graciously favours with heavenly, holy guidance and their path is the path of God, their religion is the faith of God, and their law is the law of God, so whoever follows them is guided to the straight path.

‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani, (Keys to the Arcana, tr. Mayer, 179-180)

The objective basis for claiming that the Qur’an is miraculous and inimitable (mu‘jiz), i.e. that it is beyond the productive capacity of ordinary human beings, lies within the objective literary standards, forms, and structures of the Arabic language. “Though, to be sure, the question of the literary merit is one not to be judged on a priori grounds but in relation to the genius of Arabic language” (Sir Hamilton Gibb). Only experts in Arabic language and literature can truly determine and judge the quality of an Arabic literary production by objective standards. Therefore, we have compiled a series of testimonies from three groups of experts:

Non-Muslim modern European scholars of the Arabic language and literature

Modern Arab scholars of Arabic literature

Classical Muslim scholars of Arabic language and literature.

Each testimonial individually and all of them collectively show the broad consensus among modern and pre-modern scholars, both non-Muslim and Muslim, that:

The Qur’an’s literary form (nazm) is inimitable because it transcends and falls outside the scope, qualities, and definition of all Arabic poetry and prose through history

The early reception of the Qur’an shows that its original listeners – among Muhammad’s followers and his fiercest opponents – perceived the Qur’an as miraculous and inimitable: several experts of the Arab language in Muhammad’s lifetime attested to the superiority of the Qur’an over all Arab speech including: al-Walid b. al-Mughira, al-Tufayl b. ‘Amr al-Dawsi, Hassan b. Thabid, Labid b. Rabi‘a, Ka‘b b. Malik, Suwayd b. al-Samit. No person in Muhammad’s lifetime successfully produced a literary production that was equal to the Qur’an.

There has been no successful attempt in the history of Arabic language and literature to imitate the literary form of the Qur’an. All the experts in Arabic literature, poetry, and grammar from Islamic civilization testify to the Qur’an’s inimitability: al-Jahiz (d. 868), al-Nazzam (d. c. 840), Hisham al-Fuwati (d. 833), Abu Muslim al-Isfahani (d. 934), Abu Hatim al-Razi (d. 934), al-Rummani (d. 994), al-Baqillani (d. 1013), al-Sharif al-Murtada (d. 1044), Shaykh al-Mufid (d. 1032), Ibn Hazm (d. 1064), Abu Ishaq Isfara’ini (d. 1027), al-Ash‘ari (d. 935), al-Juwayni (d. 1085), ‘Abd al-Jabbar (d. 1025), ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jurjani (d. 1078), al-Shahrastani (d. 1153).

In every Qur’an verse, the selection, combination, and arrangements of words, grammatical constructs, and rhetorical devices are “finely-tuned” with the expressed meaning, such that no formal alternation is possible without severely compromising the aesthetic form or the expressed meaning of that verse (three sample verses are examined).

The full list of expert testimony can be read in Appendix A at the bottom of the article. However, a small sample of the expert testimony is quoted below:

Though, to be sure, the question of the literary merit is one not to be judged on a priori grounds but in relation to the genius of Arabic language; and no man in fifteen hundred years has ever played on that deep-toned instrument with such power, such boldness, and such range of emotional effect as Mohammad did…the Meccans still demanded of him a miracle, and with remarkable boldness and self confidence Muhammad appealed as a supreme confirmation of his mission to the Koran itself. Like all Arabs they were connoisseurs of language and rhetoric. Well, then if the Koran were his own composition other men could rival it. Let them produce ten verses like it. If they could not (and it is obvious that they could not), then let them accept the Koran as an outstanding evidential miracle.

Sir Hamilton A.R. Gibb (Professor of Arabic, Harvard University, d. 1971),

(Islam: A Historical Survey, Oxford University Press, 25-28)

The Qur’an is the greatest book and the most powerful literary work in the Arabic language, for it has made that language immortal and preserved its essence, and the Quran has become immortal with it; the Quran is the pride of the Arabic language and the jewel of its tradition, and the Arabs know this quality of the Quran, though they may differ in their faith or in their inclinations – they feel that it is the essence of what distinguishes Arabic.

Dr. Amin al-Khuli (Egyptian Scholar of Arabic Literature and the Qur’an, d. 1966),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 84-85)

I do, however, believe that Muhammad, like the earlier prophets, had genuine religious experiences. I believe that he really did receive something directly from God. As such, I believe that the Qur’an came from God, that it is Divinely inspired. Muhammad could not have caused the great upsurge in religion that he did without God’s blessing. The diagnosis of the Meccan situation by the Qur’an is that the troubles of the time were primarily religious, despite their economic, social and moral undercurrents, and as such capable of being remedied only by means that are primarily religious. In view of Muhammad’s effectiveness in addressing this, he would be a bold man who would question the wisdom of the Qur’an.”

W. Montgomery Watt (Christian Clergyman, Scholar of the Qur’an, Islamic History and Theology, d. 2006),

(Interview with the Coracle, 2000, Read Here)

In spite of all we know of Muhammad’s independence from his models, we must admit that the way in which he inwardly assimilated and refined the foreign words and ideas, the personal pathos with which he was able to claim all this as his own, is the true miracle of his prophethood. We understand it differently, but in a sense we must agree with Qadi Abu Bakr that the doctrine of i‘jaz (inimitability/miraculousness) of the Quran is based in reality.

Tor Andrae (Christian scholar of religion & Lutheran bishop of Linköping, d. 1947),

(Die Person Muhammeds in Lehre und Glauben seiner Gemeinde, 1918, 94)

And it would be preposterous to deny that this text, which came down over twenty years in periodically interrupted and unordered fragments, and was collected twenty years later, could [not] have gained the acceptance it has if it did not possess its, let us say, truly unique qualities.

Jacques Berque (Christian scholar of Arabic literature and Islam, d. 1995),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 9)

The Qur’an is not prose and that it is not verse either. It is rather Qur’an, and it cannot be called by any other name but this. It is not verse, and that is clear; for it does not bind itself to the bonds of verse. And it is not prose, for it is bound by bonds peculiar to itself, not found elsewhere; some of the binds are related to the endings of its verses and some to that musical sound which is all its own. It is therefore neither verse nor prose, but it is “a Book whose verses have been perfected the expounded, from One Who is Wise, All-Aware.” We cannot therefore say its prose, and its text itself is not verse. It has been one of a kind, and nothing like it has ever preceded or followed it.

Dr. Taha Husayn (Renowned Scholar of Arabic, “The Dean of Arabic Literature,” d. 1973),

(“Prose in the second and third centuries after the Hijra,” The Geographical Society, Cairo 1930: Dar al Ma‘arif)

For Muhammad, who…was not a poet and had not assimilated the fine points of rhetoric in long years of training, who did not know the secrets of syntax (nawh), diction (luga), tradition (riwaya) or metre (‘arud), who had no notion of rhetorical figures (badi‘), who did not even master writing (this was taken to be synonymous with a lack of literary training) – for such a literary layman to apply, spontaneously and without ever having shown any propensity to poetic expression, the entire system of poetic language, who no normal person could ever master in all its details; for this laymen, his soul inspired, to create out of the known material of words, figures of speech and rules of syntax and style something completely new, previously unknown and never even approach since, in such an inimitable, unprecedented and hence unlearnable way – this historic fact, verifiable and demonstrable and obvious to anyone, must appear miraculous.

Navid Kermani (German Scholar of Islam, Novelist),

(God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 218)

Let us just consider the effect that hearing the verses had on the opponents. In his regard alone, we know the names and full biographies of dozens of people who went to the Messenger of God to dispute with him, disagree with him and protest against him, and they no sooner sat down with him, heard his preaching and God’s verses, than they became muslims.’

Mahmud Ramiyar (Associate Professor of Arabic, University of Tehran),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 19)

But the initial amazement that the Qur’an produced among the Arabs was of a verbal nature. They were beguiled by its language, by its linguistic beauty and art. That language was the key that opened the door through which they could enter the world of the Qur’an and accepted Islam as a religion. Hence it is impossible to draw a dividing line at any level between Islam and language. One may even say that the early Muslims who formed the first hard core of the Islamic mission believed in the Quran primarily as a text whose linguistic expression had taken possession of them: they believed in it not because it revealed to them the secrets of being or of human existence, or brought a new order to their lives, but because they saw in it a scripture that was like nothing they had known before. Through language their nature was changed from within, and it was language that changed their lives.

Ali Ahmed Said Esber (“Adonis”, prominent Syrian Arab Poet, b. 1930),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 36)

That the best of Arab writers has never succeeded in producing anything equal in merit to the Qur’an itself is not surprising.

Dr. Edward Henry Palmer (Professor of Arabic, Cambridge University, d. 1882),

(The Qur’an, 1990, 15)

The Arabs, at the time, had reached their linguistic peak in terms of linguistic competence and sciences, rhetoric, oratory, and poetry. No one, however, has ever been able to provide a single chapter similar to that of the Qur’an.”

Dr. Hussein Abdul-Raof (Professor of Islamic Studies, Leeds University)

(Exploring the Qur’an, 2003, 64)

In the time of the Quran, the Arabs had achieved a degree of eloquence that they had never known in their prior history. In every previous era, the language had developed continuously, undergoing improvement and refinement, and had begun to shape the social customs…The kingdom of language had become established among them, but it had had no king until the Quran came to them.

Sadiq al-Rafi‘i (Syrian-Egyptian Poet and Litterateur, d. 1937),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 5)

One of the most astounding things that we can see about the miraculous nature of the Quran and the perfection of it style is that we think its forms of expression (alfaz) fit its contents (ma‘ani). Then we study it more closely and delve into it, and in the end we think its contents fit its forms of expression. Then we think it is the other way around again. We study it further and with the greatest care, and in the end we are always led to the opposite opinion, and we are torn back and forth in the conflict between these two opinions until we finally refer back to God, who created the Arabs with a linguistic talent, only to produce something out of this language that surpasses that talent.

Sadiq al-Rafi‘i (Syrian-Egyptian Poet and Literateur, d. 1937),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 121)

To read the full compilation of scholarly testimony that the Qur’an is inimitable and surpasses all human productions in the Arabic language, please fully read Appendix A at the bottom of the article at the bottom of the article.

D. Since the Qur’an spoken by Prophet Muhammad is inimitable and miraculous over all other forms of human discourse, Prophet Muhammad was the Possessor of Divine Guidance in his time-period;

E. As the Possessor of Divine Guidance, Prophet Muhammad had the unique ability to “read” the divine guidance from God’s Speech (God’s creative act) within God’s Book (the entirety of conditioned realities) and convey this divine guidance in human language through coining the appropriate symbols, expressions, and parables in Arabic tailored for the historical, cultural, and social needs of his listeners. This was possible because Muhammad possessed a higher cognitive faculty than those human beings who do not comprehend the divine guidance. The Qur’an refers to the Prophet Muhammad’s higher cognitive faculty as the “Holy Spirit” and describes this as the mechanism by which the Prophet accesses the “Book of God”:

And that We have inspired you [Muhammad] with a Spirit (ruh) from Our Command. You did not know what was the Book (al-kitab) and what was the Faith. But We have made it a Light (nur) by which We guide such of our Servants as We will. And verily, you guide to a Straight Path.

Holy Qur’an 42:52

And indeed, it is a revelation (tanzil) from the Lord of the Worlds

The Trustworthy Spirit (al-ruh al-amin) has brought it down (nazala biha)

Upon your heart (‘ala qalbika) that you may be of the warners

In a clear Arabic language (bi-lisanin ‘arabiyyin)Holy Qur’an 26:193-195

The Prophet Muhammad’s pure soul and intellect perceived the divine guidance from God’s Speech (God’s creative act) within God’s Book (the entirety of conditioned realities in their intelligible forms) as non-verbal inspiration or “light” (nur) – called the Holy Spirit; Muhammad then expressed, conveyed, and represented this non-verbal spiritual divine guidance as the Arabic Qur’an recitations. The Qur’an is the Speech and Book of God with respect to its spiritual essence and meanings and the speech and words of Prophet Muhammad with respect to its symbolic verbal form in Arabic:

Muhammad was the purest of men in spirit and the most noble in soul. His rational soul and sensible spirit were better prepared to receive the impression of divine inspiration and more attuned to the Holy Spirit with which God supported His Prophets and messengers than all the souls and spirits of mankind. Divine inspiration thus imprinted itself on his spirit because of its purity from al psychic manifestations that normally trouble the human spirit, such as caprice, envy, arrogance, greed, miserliness, tyranny, pride, and such like, all of which harm and corrupt the human spirit…This Holy Spirit imprinted itself on his sensible spirit and intermingled with his rational, virtuous, and pure soul, free from all taint and fifth…When divine inspiration imprinted itself on his spirit and he accepted it in his heart and imagined it in his thought, he openly declared it in his speech. That revelation is the firmest of all proofs of his prophecy; the clearest argument of God directed at His creatures, and the most manifest of his proofs, clear arguments, and miracles

Abu Hatim al-Razi (Ismaili Muslim scholar of Arabic language and philosophy, d. 934),

(Proofs of Prophecy, tr. Tarif Khalidi, 179-180)

Indeed, God sent down the Qur’an to His servant and His Messenger, Muhammad, as a light (nur) which the faculty of prophecy carried and which the soul of perfection and purification accepted. When the Prophet intended to convey that light to the ranks of people, he discerned that their coarse natures and turbid souls would not be able to grasp this subtlety. So, he moulded this subtle light, with connected expressions, coined examples and understandable signs in order to straighten them according to the revealed wisdom in the souls, since the ranks of people did not possess purified souls receptive to that lordly, universal light…The composing, the expressions, and the composition of the Qur’an are due to the Prophet. The Qur’an is both the Speech of God (kalam Allah) and the words of the Messenger of God (qawl al-Rasul Allah).”

Imam Ma‘add Abu Tamim al-Mu‘izz (14th Ismaili Imam, d. 975),

(Qadi al-Nu‘man, Kitab Ta’wil al-Shari‘ah, ed. Nadia E. Jamal, 4:4, 5:49)

Step 7: The Possessor of Divine Guidance after Prophet Muhammad was identified and designated by Prophet Muhammad.

Although direct Divine inspiration ceased at the Prophet’s death, the need of Divine guidance continued and this could not be left merely to millions of mortal men, subject to the whims and gusts of passion and material necessity, capable of being momentarily but tragically misled by greed, by oratory, or by the sudden desire for material advantage.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan: Islam – The Religion of My Ancestors, Read at NanoWisdoms)

A. Prophet Muhammad was the Possessor of Divine Guidance in his time-period (from Step 5).

B. There must be a Possessor of Divine Guidance in every time-period, including the time-periods after Prophet Muhammad has passed away (from Step 4 above).

C. The Possessor of Divine Guidance immediately after Prophet Muhammad was either:

a) identified and designated by Muhammad to be the next Possessor of Divine Guidance; and/or

b) uttered inimitable speech that surpasses all forms of human discourse like Muhammad did.

(from Step 5 above)

D. If Prophet Muhammad declared and identified someone as the Possessor of Divine Guidance after him, then such a person is in fact the Possessor of Divine Guidance in the time-period after Prophet Muhammad.

E. Prophet Muhammad actually did identify and designate his cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali b. ‘Abi Talib as the Possessor of Divine Guidance before his own death.

The below historical statements of Prophet Muhammad preserved in both Sunni and Shia sources show that Muhammad designated his cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali b. Abi Talib as his successor and as the Possessor of Divine Guidance whose position and authority was equal to his own (as documented here – Imam Ali declared successor of Muhammad in Sunni Sources):

Which of you, then, will help me in this, and be my brother, mine executor and my successor amongst you?’ All remained silent, except for the youthful ʿAlī who spoke up: ‘O Prophet of God, I will be thy helper in this.’ The Prophet then placed his hand on ʿAlī’s neck and said, ‘This is my brother, mine executor and my successor amongst you. Hearken unto him and obey him.’

(Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasul Allah, tr. A Guilaume, The Life of Muhammad, 118)

Truly, ‘Ali is from me and I am from him (inna ʿAlī minnī wa anā minhu), and he is the walī (patron/spiritual master) of every believer after me.

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 19, No. 4636; Ahmad b. Shu‘ayb al-Nasa’i, Khasa’is Amir al-Mu’minin ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, Tehran 1998, 129)‘Ali is with the Qurʾān and the Qurʾān is with ‘Ali. They will not separate from each other until they return to me at the [paradisal pool] (al-ḥawḍ).

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 927, No. 4685)[To ‘Ali]: Are you not happy that you should have in relation to me the rank of Aaron in relation to Moses, except that there is no prophet after me.

Prophet Muhammad,

(Ahmad b. Shu‘ayb al-Nasa’i, Khasa’is Amir al-Mu’minin ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, Tehran 1998, 76)Three things were revealed to me regarding ʿAlī: he is the leader of the Muslims, the guide of the pious and chief of the radiantly devout (sayyidu’l-muslimīn, imāmu’l-muttaqīn, wa qāʾidu’l-ghurra’lmuḥajjalīn).

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 936, No. 4723)Gazing upon ʿAlī is an act of worship (al-naẓar ilā ʿAlī ʿibāda).))

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 938, No. 4736)May God have mercy on ʿAlī. O God, make the truth revolve around ʿAlī wherever he turns (adiri’l-ḥaqq maʿahu ḥaythu dāra)

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 927, No. 4686)‘Ali is as my own soul (ka-nafsī).

Prophet Muhammad,

(Ahmad b. Shu‘ayb al-Nasa’i, Khasa’is Amir al-Mu’minin ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, Tehran 1998, 104)You [‘Ali] are from me and I am from you (anta minnī wa anā minka).

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 924, No. 4672)Whoever obeys ʿAli obeys me, and whoever disobeys him disobeys me.

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 925, No. 4678)[To ‘Ali]: You will clarify for my community that over which they will differ after me.

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 926, No. 4678)There is one amongst you who will fight for the taʿwīl [spiritual interpretation] of the Qurʾān as I have fought for its tanzīl [literal revelation].’ Abū Bakr asked, ‘Is it I?’. The Prophet said, ‘No’. ʿUmar asked, ‘Is it I?’. The Prophet said, ‘No, it is the one who is mending the sandal.’ The Prophet had given ʿAlī his sandal to mend.

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 926, No. 4679)O ʿAli, whoever separates himself from me separates himself from God, and whoever separates himself from you, O ʿAli, separates himself from me.

Prophet Muhammad,

(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, Al-Mustadrak ‘ala’l-Sahihayn, Beirut 2002, 927, No. 4682)‘Ali is from me and I am from him (ʿAlī minnī wa anā minhu), and nobody can fulfill my duty but myself and ʿAli.

Prophet Muhammad,

(Ahmad b. Shu‘ayb al-Nasa’i, Khasa’is Amir al-Mu’minin ‘Ali b. Abi Talib, Tehran 1998, 106)He whose mawlā [master] I am, this ʿAlī is his mawla (man kuntu mawlāhu fa-ʿAlī mawlāhu).

Prophet Muhammad,

(Cited in numerous Sunni Muslim Hadith sources listed here)

Appendix A: Evidence that the Qur’an uttered by Prophet Muhammad is inimitable miraculous speech

The Qur’an’s literary form is inimitable and miraculous compared to all other forms of Arabic speech – as testified to and affirmed by numerous Orientalist and Western scholars of Arabic literature, the subjective experience of the Qur’an by Muhammad’s contemporaries and Muslim communities over the centuries, and the unanimous scholarly opinion of Muslim theologians, philosophers, and grammarians.

By the terms – miracle/miraculous or inimitability/inimitable (i‘jaz) – we do not mean a “break in the laws of nature” or a “divine intervention” in the ordinary course of events. As already explained, God creates and sustains all existence at every moment – so divine “interventions” are wholly unnecessary: the laws of nature are never broken because they are the manifestation of God’s continuous creation and guidance in the Universe. When we say that a certain production is “inimitable” or “miraculous”, we mean that such a production transcends the capacities of a certain class or species and is beyond the productive capabilities of that species. Thus, a production is only inimitable or miraculous in relation to some standard or capacity. For example, human rational discourse and its various products like science, poetry, art, abstract thought, etc. are certainly “inimitable” and “miraculous” with respect to the animal species. In the same way, when we say that the Qur’an is inimitable and miraculous with respect to human beings, this means that the literary form (nazm) of the Qur’an together with its meaning is a speech or discourse that transcends the productive capacity of human beings who are not divinely-inspired prophets. The fact that the Qur’an is inimitable constitutes the greatest proof that Prophet Muhammad was the Possessor of Divine Guidance in his lifetime and a divinely-inspired Prophet.

Just as the movements of a human being come to be the inimitable miracles for an animal, namely the human being’s movements pertaining to thought, speech and action, likewise the movements of the Prophets come to be the inimitable miracles for the human being, namely their movements pertaining to the innate predisposition, to revelation and character – for they are those whom God graciously favours with heavenly, holy guidance and their path is the path of God, their religion is the faith of God, and their law is the law of God, so whoever follows them is guided to the straight path.

‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani, (Keys to the Arcana, tr. Mayer, 179-180)

The objective basis for claiming that the Qur’an is miraculous and inimitable (mu‘jiz), i.e. that it is beyond the productive capacity of ordinary human beings, lies within the objective literary standards, forms, and structures of the Arabic language. “Though, to be sure, the question of the literary merit is one not to be judged on a priori grounds but in relation to the genius of Arabic language” (Sir Hamilton Gibb). Only experts in Arabic language and literature can truly determine and judge the quality of an Arabic literary production by objective standards. Therefore, we have compiled a series of testimonies from three groups of experts:

Non-Muslim modern European scholars of the Arabic language and literature;

Modern Arab scholars of Arabic literature;

Classical Muslim scholars of Arabic language and literature.

Each testimonial individually and all of them collectively show the broad consensus among modern and pre-modern scholars, both non-Muslim and Muslim, that:

The Qur’an’s literary form (nazm) is inimitable because it transcends and falls outside the scope, qualities, and definition of all Arabic poetry and prose through history

The early reception of the Qur’an shows that its original listeners – among Muhammad’s followers and his fiercest opponents – perceived the Qur’an as miraculous and inimitable: several experts of the Arab language in Muhammad’s lifetime attested to the superiority of the Qur’an over all Arab speech including: al-Walid b. al-Mughira, al-Tufayl b. ‘Amr al-Dawsi, Hassan b. Thabid, Labid b. Rabi‘a, Ka‘b b. Malik, Suwayd b. al-Samit. No person in Muhammad’s lifetime successfully produced a literary production that was equal to the Qur’an.

There has been no successful attempt in the history of Arabic language and literature to imitate the literary form of the Qur’an. All the experts in Arabic literature, poetry, and grammar from Islamic civilization testify to the Qur’an’s inimitability: al-Jahiz (d. 868), al-Nazzam (d. c. 840), Hisham al-Fuwati (d. 833), Abu Muslim al-Isfahani (d. 934), Abu Hatim al-Razi (d. 934), al-Rummani (d. 994), al-Baqillani (d. 1013), al-Sharif al-Murtada (d. 1044), Shaykh al-Mufid (d. 1032), Ibn Hazm (d. 1064), Abu Ishaq Isfara’ini (d. 1027), al-Ash‘ari (d. 935), al-Juwayni (d. 1085), ‘Abd al-Jabbar (d. 1025), ‘Abd al-Qadir al-Jurjani (d. 1078), al-Shahrastani (d. 1153).

In every Qur’an verse, the selection, combination, and arrangements of words, grammatical constructs, and rhetorical devices are “finely-tuned” with the expressed meaning, such that no formal alternation is possible without severely compromising the aesthetic form or the expressed meaning of that verse (three sample verses are examined).

Evidence #1: The Qur’an is inimitable because its literary form (nazm) is inimitable and surpasses all literary genres and forms of Arabic poetry and prose.

The Qur’an is the greatest book and the most powerful literary work in the Arabic language, for it has made that language immortal and preserved its essence, and the Quran has become immortal with it; the Quran is the pride of the Arabic language and the jewel of its tradition, and the Arabs know this quality of the Quran, though they may differ in their faith or in their inclinations – they feel that it is the essence of what distinguishes Arabic.

Dr. Amin al-Khuli (Egyptian Scholar of Arabic Literature and the Qur’an, d. 1966),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 84-85)

I do, however, believe that Muhammad, like the earlier prophets, had genuine religious experiences. I believe that he really did receive something directly from God. As such, I believe that the Qur’an came from God, that it is Divinely inspired. Muhammad could not have caused the great upsurge in religion that he did without God’s blessing. The diagnosis of the Meccan situation by the Qur’an is that the troubles of the time were primarily religious, despite their economic, social and moral undercurrents, and as such capable of being remedied only by means that are primarily religious. In view of Muhammad’s effectiveness in addressing this, he would be a bold man who would question the wisdom of the Qur’an.”

W. Montgomery Watt (Christian Clergyman, Scholar of the Qur’an, Islamic History and Theology, d. 2006),

(Interview with the Coracle, 2000, Read Here)

In spite of all we know of Muhammad’s independence from his models, we must admit that the way in which he inwardly assimilated and refined the foreign words and ideas, the personal pathos with which he was able to claim all this as his own, is the true miracle of his prophethood. We understand it differently, but in a sense we must agree with Qadi Abu Bakr that the doctrine of i‘jaz (inimitability/miraculousness) of the Quran is based in reality.

Tor Andrae (Christian scholar of religion & Lutheran bishop of Linköping, d. 1947),

(Die Person Muhammeds in Lehre und Glauben seiner Gemeinde, 1918, 94)

And it would be preposterous to deny that this text, which came down over twenty years in periodically interrupted and unordered fragments, and was collected twenty years later, could [not] have gained the acceptance it has if it did not possess its, let us say, truly unique qualities.

Jacques Berque (Christian scholar of Arabic literature and Islam, d. 1995),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 9)

It is as though Muhammad had created an entirely new literary form that some people were not ready for but which thrilled others. Without this experience of the Koran, it is extremely unlikely that Islam would have taken root.

Karen Armstrong (British scholar of religions), (A History of God, 1994, 78)

But you know that the Qur’an is not prose and that it is not verse either. It is rather Qur’an, and it cannot be called by any other name but this. It is not verse, and that is clear; for it does not bind itself to the bonds of verse. And it is not prose, for it is bound by bonds peculiar to itself, not found elsewhere; some of the binds are related to the endings of its verses and some to that musical sound which is all its own. It is therefore neither verse nor prose, but it is “a Book whose verses have been perfected the expounded, from One Who is Wise, All-Aware.” We cannot therefore say its prose, and its text itself is not verse. It has been one of a kind, and nothing like it has ever preceded or followed it.”

Dr. Taha Husayn (Foremost Scholar and Literary Critic of Arabic “The Dean of Arabic Literature”), (“Prose in the second and third centuries after the Hijra,” The Geographical Society, Cairo 1930: Dar al Ma‘arif)

All Arabic poetry has meter. The “meter” refers to the pattern of short and long syllables in a line of poetry. Historically, all Arabic poetry – before Muhammad and after Muhammad – contains one of sixteen possible meters: 1) al-tawil, 2) al-bassit, 3) al-wafir, 4. al-kamil, 5. al-rajas, 6. al-khafif, 7. al-hazaj, 8. al-muttakarib, 9. al-munsarih, 10. al-muktatatb, 11. al-muktadarak, 12. al-madid, 13. al-mujtath, 14. al-ramil, 15. al-khabab, 16. al-saria’. It is an objective historical fact that the Qur’an does not conform to any one of the sixteen Arabic metrical forms.

A person had to study for years, sometimes even for decades under a master poetic before laying claim to the title of poet. Muhammad grew up in a world which almost religiously revered poetic expression. He had not studied the difficult craft of poetry, when he started reciting verses publicly. Muhammad’s recitations differed from poetry and from the rhyming prose of the soothsayers, the other conventional form of inspired, metrical speech. The norms of old Arabic poetry were strangely transformed, the subjects developed differently, and the meter was abandoned. While poetry was, in political terms, generally conservative, reinforcing the moral and social order of the day, the whole impetus of the early Qur’an, its topics, metaphors and ideological thrust, was towards revolutionary change. All this was new to Muhammad’s contemporaries.

Navid Kermani, (“Poetry and Language”, in Rippin, The Blackwell Companion to the Qur’an, 108-109)

Likewise, the Qur’an does not conform to the definition and structures of Arabic prose. There are two kinds of Arabic prose – rhyming speech called saj‘ and ordinary speech. The Qur’an contains some rhyming but it falls outside the scope of both rhyming prose and non-rhyming speech.

Thus, as regards its external features, the style of the Koran is modelled upon saj’, or rhymed prose…but with such freedom that it may fairly be described as original.

R. A. Nicholson (Professor of Arabic, University of Cambridge),

(Literary History of the Arabs, 159)

Those passages from the Qur’an that approach saj’ still elude all procrustean efforts to reduce them to an alternative form of saj‘ (rhyming speech).

Bruce Lawrence (Professor of Religions, Duke University),

(Journal of Qur’anic Studies, Vol VII, Issue I 2005. “Approximating Saj’ in English Renditions of the Qur’an: A Close Reading of Suran 93 (al-Duha) and the basmala”, 64)

The Qur’an is not verse, but it is rhythmic. The rhythm of some verses resemble the regularity of saj’…But it was recognized by Quraysh critics to belong to neither one nor the other category.

A.F.L. Beeston, T.M. Johnstone, R.B. Serjeant and G.R. Smith (Orientialist Scholars of Arabic Literature), (Arabic Literature To The End Of The Umayyad Period, 1983, 34)

For the Koran is neither prose nor poetry, but a unique fusion of both.

Dr. Arthur J. Arberry (Professor of Arabic, Cambridge University),

(The Koran. Oxford University Press, x)

The ‘break with the familiar’ is grounded in the fact that the known forms of oratory up to then were shi‘r (poetry), saj‘ (rhyming prose), khaṭab, rasa’il and spoken prose, and the Qur’an came with a unique literary idiom that was different from everything familiar and at the same time attained a degree of beauty with which it exceeded all other forms, and even the art of verse, which is the most beautiful speech of all.

Abu’l-Hasan al-Rummani (Renowned Grammarian of Baghdad, d. 994),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 81)

The verses of the Qur’an represent its uniqueness and beauty not to mention its novelty and originality. That is why it has succeeded in convincing so many people of its truth. It imitates nothing and no one nor can it be imitated. Its style does not pale even after long periods of study and the text does not lose its freshness over time.

Oliver Leaman (Professor of Philosophy, University of Kentucky),

(The Qur’an: An Encyclopedia, 2006, 404)

Over the last three decades, I have managed to read the whole Qur’an well over fifty times; my reading has shifted recently to reading the Qur’an for linguistic and rhetorical analysis…I have finally reached an independent conclusion based on translation theory and linguistic analysis that the Qur’anic discourse is inimitable and cannot be reproduced into a target language.

Dr. Hussein Abdul-Raof (Professor of Islamic Studies, University of Leeds),

(Qur’an Translation: Discourse, Text, and Analysis, 3)

Evidence #2: The Qur’an’s aesthetic beauty profoundly affected and transformed Muhammad’s contemporaries: many individuals accepted Muhammad’s prophethood and divine inspiration by merely hearing him recite the Qur’an:

Beauty, in most canons, has this divine quality. It is a manifestation of the Infinite on a finite plane and so introduces something of the Absolute into the world of relativities. Its sacred character “confers on perishable things a texture of eternity…Beauty is distinct but not separate from Truth and virtue.” As Aquinas affirmed, beauty relates to the cognitive faculty and is thus concerned with wisdom.

Harry Oldmeado, (Frithjof Schuon and the Perennial Philosophy, 157-158)

What ultimately led in the ninth century to the formulation of the dogma of the inimitability and uniqueness of the Quran is a central experience of inner life and inner radiance, a very real experience of metaphysical beauty of the revealed scripture – not mere theological speculation or scholarly sophistry. The doctrine was the rationalization of a fundamental experience of the whole religious community – even if this experience was limited in its horizon and its rationalization did not take sufficient notice, or sufficiently serious notice, of the experience of other groups.

Dr. Angelika Neuwirth (German Scholar of Qur’anic Studies),

(Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 195)

We can infer from the Quran that the Prophet regularly visited the Kaba in the early years of his vocation to recite the revealed verses. The first few believers, who threw themselves on the ground or wept during his recitation, gathered around him, along with increasing numbers of curious listeners. Muhammad’s opponents were often present as well…Up to this point, the account of Muhammad’s preaching given by the later tradition matches the recitation scenario that we can infer from the Qur’an itself, which has some actual historical value.

Navid Kermani, God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 11)

The greatest of Arabia’s poets of Labid ibn Rabi‘a. His poems hung on the doors of the Kaaba as a sign of his triumph. None of his fellow poets dared to challenge him by hanging their verses beside Labid’s. But, one day, some followers of Muhammad approached. Muhammad was decried by the heathen Arabs of that time as an obscure magician and a deranged poet. His followers hung an excerpt from the second surah of the Quran on the door and challenged Labid to read it aloud. The king of poets laughed at their presumption. Out of idleness, or perhaps in mockery, he condescended to recite the verses. Overwhelmed by their beauty, he professed islam on the spot.

Navid Kermani, (God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 1)

Besides poets, another group of people who were particularly receptive to the beauty of the Quran, if we believe the traditions, were Muhammad’s particularly aggressive enemies: Meccans such as Unays and ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, who at first fiercely opposed the Prophet but then spontaneously joined him when they heard his recitation. ‘Let us just consider the effect that hearing the verses had on the opponents, Mahmud Ramiyar comments. ‘In this regard alone, we know the names and full biographies of dozens of people who went to the Messenger of God to dispute with him, disagree with him and protest against him, and they no sooner sat down with him, heard his preaching and God’s verses, than they became muslims.’

Navid Kermani, (God is Beautiful: The Aesthetic Experience of the Qur’an, 19)