The Aga Khan’s Direct Descent from Prophet Muhammad: Historical Proof

“I am the 49th hereditary Imam in direct lineal descent from the first Shia Imam, Hazrat ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib through his marriage to Bibi Fatimat-az-Zahra, our beloved Prophet’s daughter.”

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,

(Letter to International Islamic Conference, Amman, July 2005, Read at NanoWisdoms)

The purpose of this article is to present the independent historical documentation that proves (as far as the historical method can show) that Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni is the direct lineal descendant of Prophet Muhammad and Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib in an unbroken line of descent.

Today there are many Muslims known as Sayyids and Shariffs who claim direct descent from Prophet Muhammad. The “proof” that a Sayyid or Shariff family provides for their lineage usually consists of just a family tree. Sometimes, a small village or community or scholar(s) also testify to the Sayyid’s or Shariff’s lineage. But beyond the family tree, the Sayyids and Shariffs do not offer any more evidence. In comparison, Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni has a full family tree of his ancestry (the 49 Imams) – which appears in numerous centuries-old Ismaili texts from Persia, Central Asia, and India. Secondly, in addition to the family tree, Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni and each of his ancestors have had an Ismaili community in every generation that testifies to and recognizes their Fatimid ‘Alid lineage. Thirdly, Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni’s lineage can be independently historically corroborated through third-party historical documentation (centuries-old texts, documents, tombstones, genealogy trees, treatises, histories, etc.), much of which has been produced by non-Ismailis. Much of this independent historical documentation for each generation of the lineage of 49 Ismaili Imams is presented and summarized in this article. The article provides a historical summary of the life of each of the 49 Imams and lists the major primary historical sources that mention the existence of each Imam in the lineage up to the present day, followed by citing the academic secondary studies that document these primary sources. This is the first article that presents a historical documentation of Imam Shah Karim al-Husayn’s lineage and we reference major academic publications on Ismaili history throughout. Before going into the historical documentation of the Imam’s lineage, we will first present a theological “proof” of Shah Karim al-Husayni’s Imamat that does not require independent historical documentation for the Imam’s entire lineage.

A. The Theological Proof of the Imamat

The Muslims are divided into two main branches: the Shia Muslims and the Sunni Muslims. I suppose one could compare it to the division in the Christian Church between Protestants and Catholics. The main difference is that the Shi‘a accept the members of the Prophet’s family as the rightful successors to the Prophet in his religious heritage…My family and myself trace our family line back to the Prophet and are accepted therefore by the community as the Imams.

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,

(Pacemakers – A Man of the World: The Aga Khan 1967, Read at NanoWisdoms)

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV is the 49th hereditary Imam of the Shi‘i Ismaili Muslims. By defining himself as the hereditary Imam of the Ismailis, Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni claims the following roles and status:

• the holder of a divinely-ordained leadership office, called the Imamat, which succeeds to the spiritual and moral authority of the Prophet Muhammad

• responsible for providing an infallible interpretation of Islam with respect to any time/context of human history and with respect to the esoteric meaning of the Revelation to Muhammad.

• the spiritual intercessor/intermediary between humanity and God with respect to divine guidance, authority, blessings and purification (the Prophet himself performed this function)

• the direct descendant of Prophet Muhammad through an unbroken line of descent going back to Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib (the paternal cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad) and the Prophet’s daughter Hazrat Fatimah al-Zahra.

A pivotal issue discussed today among both Ismailis and non-Ismailis is the question of “proof” for the Imamat of Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV. In general, there are several ways or methods of establishing evidence to prove that the Aga Khan’s claim to Imamat is true and legitimate. Ismaili Gnosis’ contemporary reconstruction of the traditional “Proof of Imamat” is as follows:

A. Establishing the Existence of God and the Revelation to Prophet Muhammad:

Step 1: There is one absolutely transcendent and eternal God who originates and continuously sustains all realities (Read a Proof for God’s Existence).

Step 2: God continually bestows divine guidance upon all created beings; there is always at least one divinely-inspired human being in every generation who, by this divine inspiration, comprehends ALL of God’s guidance for human wellbeing and communicates this guidance to humanity; Prophet Muhammad was the possessor and transmitter of divine guidance during his lifetime and the Qur’an, which is inimitable and miraculous speech, is the outward public sign of his divine inspiration (Read the Proof of Muhammad’s Prophethood ). For evidence that Prophet Muhammad was a real historical figure and that the Qur’an as it exists today contains his utterances, Read the Historical Evidence for Prophet Muhammad and the Qur’an.

Step 3: Prophet Muhammad’s spiritual functions and duties, as laid out in the Qur’an, include being: the holder of divine authority on God’s behalf, the mediator and intercessor between God and humanity, the channel of God’s blessings, favours, and purification, and the locus of manifestation of God’s names and attributes; by logical necessity, there must be a divinely-inspired successor to the Prophet’s religious authority and spiritual functions that he performed over his 23 year mission (Read on Muhammad’s Special Theological Status per the Qur’an).

B. Establishing Hereditary Imamat in the progeny of Prophet Muhammad and Imam ‘Ali:

Step 4: Prophet Muhammad’s successors must be divinely-appointed from his family and line of descendants, just as God appointed the successors of past Prophets and Messengers discussed in the Qur’an, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, Imran, Zakariyyah, etc. from among their family members and descendants (Read on the Qur’anic Concept of Hereditary Leadership & Succession in Prophets’ Families).

Step 5: Prophet Muhammad appointed his paternal cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib to be his successor as the master of all the believers after him (Read the Proof that Prophet Muhammad Appointed Imam ‘Ali as his Successor).

C. Establishing the Imamat of the lineage of Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far al-Sadiq and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir:

Step 6: Among the descendants of Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib, the succession to the Prophet or the Imamat, continues in the line of Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far al-Sadiq (Read Seven Arguments for the Succession of Imam Isma’il).

Step 7: Among the descendants of Imam Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far al-Sadiq, the Imamat continues through Nizar ibn al-Mustansir because Nizar was officially designated as the Imam by his father Imam Mustansir bi’llah (as attested to in multiple historical sources including Nuwayri, Ibn Athir, Maqrizi, etc. and academic studies, viz. Daftary, Walker, Wiley, Fyzee, etc.).

D. Establishing the Imamat of Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan:

Step 8: If the hereditary Imamat in the progeny of Prophet Muhammad and Imam ‘Ali is true, and if this hereditary Imamat was designated to the line of Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir, then, the true Imam in any given period of human history must claim and trace his descent and Imamat from both Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir. Consequently, any Imamat claimant who does not trace his Imamat to both Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir is not the true Imam.

Step 9: In the present day and time, Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV is the only claimant to the Imamat who traces and claims his Imamat from both Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir. Meanwhile the hidden Imam of the Ithna ‘Ashari Shi‘a descended from Musa Kazim instead Isma‘il, and the concealed Imam of the Bohras descended from Must‘ali instead of Nizar. Neither the Ithna ‘Ashari nor the Bohra Imams claimed their respective Imamats through both Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir.

Step 10: Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV, the only claimant to the Imamat who traces his lineage through both Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir, is the true and legitimate Imam in directl lineal descent from Prophet Muhammad and Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib.

Related Questions about Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV and Ismaili Doctrine:

• To learn about the personal life and daily schedule of the Aga Khan, including the many sacrifices he has made in performing the duties of the Imamat, read here.

• To see how Ismaili Muslims understand Tawhid (the Oneness of God), read here.

• To understand the concept and basis of Ismaili Muslim interpretation (ta’wil) of the Qur’an, read here.

• To understated why Ismaili Muslim prayers seek the help and blessings of the Imams, read here.

• To get an idea of the 1,400 year history of persecution faced by the Ismaili Imams and the Ismaili communities, read here.

Please note that the above proof does not require you to independently historically corroborate the Aga Khan’s claim to direct lineal descent from Prophet Muhammad. Once it is established theologically that there must always be a hereditary Imamat in the world from the direct lineal descent of Prophet Muhammad (whose descendants only come through Imam ‘Ali), it is simply a matter of confirming who the legitimate holder of this Imamat actually is – since it is not possible for the line of Imamat to just cease to exist. The above proof only requires you to historically corroborate and substantiate the specific Imamat designation of Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far and Nizar ibn al-Mustansir by their own fathers. Once these two designations are historically substantiated (which they are as per all the historical evidence), then the true Imam at any time (and this Imam always physically exists in the world) will always be a descendant of both Isma‘il and Nizar. Because there is only one person claiming Imamat from the line of both Isma‘il and Nizar and no other person in the world makes a counter-claim to the same Imamat lineage, it logically follows that this one claimant – Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV – is the true Imam by logical necessity. (If there were two or more claimants to the Ismaili-Nizari Imamat, then the matter would be more complicated – but this is not the case). From this proof, Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni’s Imamat becomes established without the need to independently corroborate and confirm every single generation in his unbroken lineage back to Prophet Muhammad.

Nevertheless, for those who do not like “theological demonstration” and prefer a purely historical approach to the Ismaili Imam’s lineage, the historical documentation for the unbroken Fatimid ‘Alid lineage of Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan is presented below.

B. The Historical Proof for Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni’s Unbroken Fatimid Lineage

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni consistently makes the public claim that he comes from an unbroken lineage of hereditary Imams going back to Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib. For example, the following quotes from the Imam’s speeches and interviews (and those of his grandfather) present this claim:

Our family claims direct descent from the Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and his beloved son-in-law Ali: and we are also descended from the Fatimite Caliphs of Egypt.

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan, 1954, 7)

This Imamat, which was Hazrat ‘Ali’s, descended through him in the sixth generation to Isma‘il from whom I myself claim my descent and my Imamat.

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan, 1954, Read at NanoWisdoms)

I have been the bearer of the “Nur” a word which means “The Light”. The Nur has been handed down in direct descent from the Prophet.

(1965: The Sunday Times Interview, Read at NanoWisdoms)

My family and myself trace our family line back to the Prophet and are accepted therefore by the community as the Imams.

(1967: Documentary – Pacemakers: A Man of the World, Read at NanoWisdoms)

Ismailis are Shi‘ite Muslims and my family descends from Ali. I am the forty-ninth Imam after him.

(1975: L’Expansion Interview, Roger Priouret, Read at NanoWisdoms)

There is a living Imam who traces his family back to Hazrat Ali.

(1985: Independent Television (ITV) Interview, Read at NanoWisdoms)

Ismailis are united by a common allegiance to the living hereditary Imam of the time in the progeny of Islam’s last and final Prophet Muhammad.

(2005: The Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat Foundation Stone Ceremony, Read at NanoWisdoms)

I am the 49th hereditary Imam in direct lineal descent from the first Shia Imam, Hazrat Ali ibn Abi Talib through his marriage to Bibi Fatimat-az-Zahra, our beloved Prophet’s daughter.”

(2005: Message to The International Islamic Conference, Read at NanoWisdoms)

I was born into a Muslim family, linked by heredity to Prophet Muhammad (may peace be upon him and his family).

(2007: Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), Graduation Ceremony, Read at NanoWisdoms)

The leadership is hereditary, handed down by Ali’s descendants, and the Ismailis are the only Shi‘a Muslims to have a living Imam, namely myself…It is the presence of the living Imam that makes our Imamat unique.

(2010: Interview – The Power of Wisdom, Read at Simerg)

Today the Ismailis are the only Shia community who, throughout history, have been led by a living, hereditary Imam in direct descent from the Prophet.

(2014: Speech to Canadian Parliament & Senate, Read at NanoWisdoms)

The Ismailis are the only Muslim community that has been led by a living, hereditary Imam in direct descent from Prophet Muhammad.

(2015: Harvard University Jodidi Lecture, Read at NanoWisdoms)

For each Imam, this article offers some information about their life and then lists the major primary historical sources and sometimes archaeological sources that document the existence of that Imam. In general, this article summarizes historical documentation that confirms the historical existence of each of the 49 Imams in Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni’s unbroken lineage to Prophet Muhammad. We have divided the history of the 49 Ismaili Imams into the below ten periods. Readers can click on each period or skip to a specific Imam, or they may scroll and skim through each Imam in historical order.

1. The Period of the Early Shi‘i Imams:

Imam ‘Ali b. Abi Talib (632-661); Imam al-Husayn (661-680); Imam ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin (680-713); Imam Muhammad al-Baqir (713-743); Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq (743-765); Imam Isma‘il b. Ja‘far (765-ca. 775); Imam Muhammad b. Isma‘il (775-ca.806)

2. The Pre-Fatimid (First) Period of Concealment:

Imam ‘Abdullah b. Muhammad al-Wafi (ca. 806-828); Imam Ahmad b. ‘Abdullah al-Taqi (828-ca. 870); Imam al-Husayn b. ‘Ahmad al-Radi (ca. 870-ca. 880-81)

3. The Fatimid Period of the Imam-Caliphs:

Imam al-Mahdi bi’llah (881-934); Imam al-Qa’im bi-amr Allah (934-946); Imam al-Mansur bi’llah (946-953); Imam al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah (953-975); Imam al-‘Aziz bi’llah (975-996); Imam al-Hakim bi-amr Allah (996-1021); Imam al-Zahir li-‘izaz Din Allah (1021-1036); Imam al-Mustansir bi’llah (1036-1094); Imam Nizar al-Mustafa Din Allah (1094-1095)

4. The Post-Fatimid (Second) Period of Concealment:

Imam al-Hadi (1095 – ca. 1132); Imam Muhammad al-Muhtadi (ca. 1132-ca. 1161-62); Imam al-Qahir (ca. 1161–ca. 1164)

5. The Alamut Period in Persia:

Imam Hasan ‘ala-dhikrihi al-salam (1164-1166); Imam ‘Ala Muhammad (1166-1210); Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan (1210-1221); Imam ‘Ala’ al-Din Muhammad (1221-1255); Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah (1255-1257)

6. The Post-Alamut (Third) Period of Concealment:

Imam Shams al-Din Muhammad (1257-1310);

Imam Qasimshah (1310-1368); Imam Islamshah (1368-1424); Imam Muhammad b. Islamshah (1424-1464)

7. The Anjudan Period of Revival:

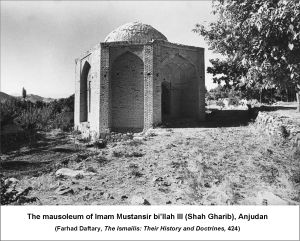

Imam Mustansir bi’llah II (1464-1480); Imam ‘Abd al-Salam Shah (1480-1494); Imam Gharib Mirza Mustansir bi’llah III (1494-1498)

8. The Safavid Period (Fourth) Period of Concealment:

Imam Abu Dharr ‘Ali (1498 – ca. 1509); Imam Murad Mirza (ca. 1509-1574); Imam Dhu’l-Faqar ‘Ali Khalil Allah I (1574-1634); Imam Nur al-Din ‘Ali (1634-1671); Imam Khalil Allah II (1671-1680); Imam Shah Nizar II (1680-1722); Imam Sayyid ‘Ali (1722-1754)

9. The Post-Safavid Period of Re-Emergence:

Imam Hasan ‘Ali (ca. 1736-ca. 1747); Imam Qasim ‘Ali (ca. 1747-ca. 1756); Imam Abu’l-Hasan ‘Ali (ca. 1756-1792); Imam Khalil Allah III (1792-1817)

10. The Modern Age of the Aga Khans:

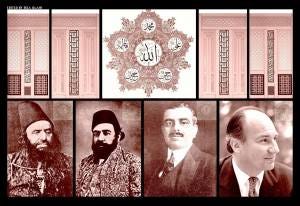

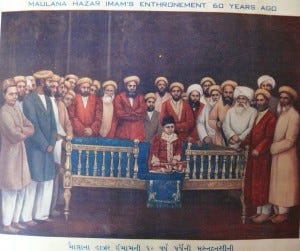

Imam Hasan ‘Ali Shah Aga Khan I (1817-1881); Imam Aqa ‘Ali Shah Aga Khan II (1881-1885); Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III (1885-1957); Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV (1957-present)

Please note that out of the 49 Ismaili Imams, at least 11 Imams were killed or murdered [along with many family members] (Imam ‘Ali, Imam al-Husayn, Imam al-Hakim, Imam Nizar, Imam Hasan ala-dhikrihi al-salam, Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan Imam ‘Ala al-Din Muhammad, Imam Rukn al-Din Kurshah, Imam Qasimshah, Imam Murad Mirza, Imam Khalil Allah III), 3 Imams are suspected to have been murdered (Imam Zayn al-Abidin, Imam al-Baqir, Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq), 1 Imam survived an assassination attempt (Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah), and 8 Imams faced the prospect of being killed (i.e. in combat, execution), and 18 Imams lived under persecution. This means a total of at least 44 out of 49 Imams, that is 88% of the Ismaili Imams, lived through considerable danger and only about 5 Imams have lived in total safety. Inevitably, this means that many of the Imams had to conceal themselves from the public for their own safety and continuation of the Imamat lineage. Thus, some Imams’ lives are better documented than others and for many Imams there is little available on their life events. However, as you will see, there are historical sources testifying to the specific existence of the more clandestine Imams as well.

1. The Period of the Early Shi‘i Imams:

Shi‘ites believe that the religious authority of the Muslims goes back to Ali, who was the nephew of Muhammad and also his son-in-law. This authority has descended through Ali’s descendants on the male side. Among the Shi‘ite Muslims there have been controversies over the genealogy and the true succession over the centuries. Ismailis are Shi‘ite Muslims and my family descends from Ali. I am the forty-ninth Imam after him.

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,

(L’Expansion Interview March 1975, Read at NanoWisdoms)

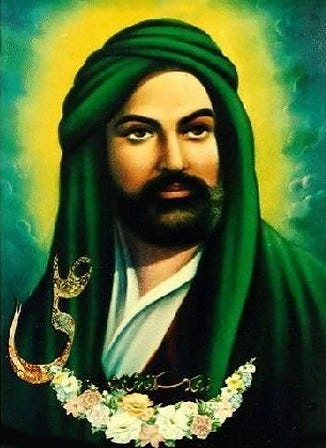

1. Imam ‘Ali b. Abi Talib (632-661):

I swear by the Lord that I know fully well all the messages of God that the Holy Prophet (may the peace of God be upon him and his descendants) has received, the ways of fulfilment of promises made by God and of all the knowledge that science or philosophy could disclose. We, the progeny of the Holy Prophet (may the peace of God be upon him and his descendants), are the doors through which real wisdom and true knowledge will reach mankind: we are lights of religion.

Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib,

(Nahjul Balagha: Sermons, letters and saying of Hazrat Ali, tr. Jafery, Syed Mohammed Askari, Khutba 123, 91)

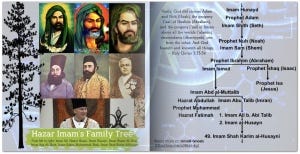

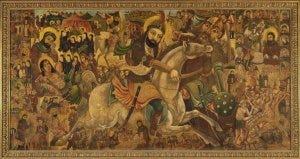

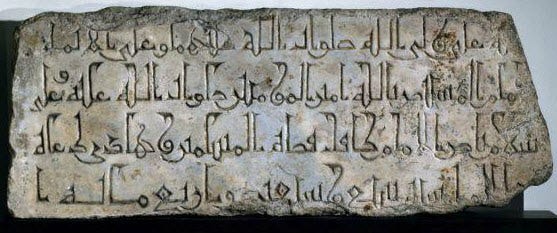

Both Prophet Muhammad and Imam ‘Ali, according to Arabian traditions and genealogy, are the direct descendants of Prophet Abraham through his son Mawlana Isma‘il (see above image). Abraham himself is the direct descendant of Prophet Adam and Prophet Noah according to Islamic and Biblical sources. Imam ‘Ali b. Abi Talib was the first cousin of the Prophet Muhammad – their fathers were brothers and they had the same grandfather. Imam ‘Ali later married Hazrat Fatimah, the Prophet’s daughter, and their children Imam al-Hasan and Imam al-Husayn were the only surviving male descendants of Muhammad. Today, all living descendants of Prophet Muhammad trace their ancestry back to al-Hasan or al-Husayn. For example, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan traces its lineage back to Imam al-Hasan. Today, Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV is called al-Husayni because his ancestry and lineage goes back to Imam al-Husayn.

Imam ‘Ali rendered a number of unique and matchless services during the Prophet’s mission and he was first appointed by Muhammad as his successor before the Banu Hashim clan when ‘Ali was about ten years old. The Prophet designated Imam ‘Ali as his successor and the legitimate authority over the community after him on several occasions (reported by numerous Sunni sources as shown here), the last of which was at Ghadeer Khum when the Prophet Muhammad proclaimed:

The Messenger of God, may God’s peace and benedictions be upon him and his progeny, said: “O people! Verily, I am leaving behind two matters (amrayn) among you – if you follow them (the two) you will never go astray. These two are: the Book of God and my Ahlul Bayt, my ‘itrah.”

Then he said thrice: “Do you know that I have more right over the believers (inni awla bi al-mu’minin) than they over themselves?”

The people said, “Yes.”

Then the Messenger of God, may God’s peace and benedictions be upon him and his progeny said, “He whose mawla (master) I am, ‘Ali also is his mawla (master).”(al-Hakim al-Naysaburi, al-Mustadrak ‘ala al-Sahihayn [Dar al-Ma’rifah li al-Tiba’ah wa al-¬Nashr: Beirut), vol. iii, pp. 109-110; For Sunni sources reporting this, see here)

Following the death of Prophet Muhammad, Shi‘i and Sunni Muslims came to differ about the nature of religious authority and its legitimate possessors. Imam ‘Ali claimed to be the rightful temporal and religious leader after the Prophet despite the political authority being assumed by Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, and later Uthman. Even some of Imam ‘Ali’s early followers regarded him as “an absolute and divinely guided leader who could demand of them the same kind of loyalty that would have been expected for the Prophet” (Maria Masse Dakake, The Charismatic Community, 57). For example, one of Ali’s supporters who was also devoted to the Prophet said to him: “our opinion is your opinion and we are in the palm of your right hand” (Dakake 58). The early followers of ‘Ali saw his guidance as “right guidance” deriving from Divine support. In other words, ‘Ali’s guidance was seen as the expression of God’s will and the Qur’anic message. The expression Din ‘Ali (the religion of ‘Ali) was also used during his own lifetime by his followers. This spiritual and religious authority of ‘Ali was known as walayah and it was inherited by his successors, the Imams. Imam ‘Ali eventually became the fourth Caliph during which he faced great opposition from the A’isha, the Prophet’s wife and the Umayyad family led by Mu‘awiyah, which led to the first civil wars. Imam ‘Ali was murdered by a Kharijite while he prayed in the mosque of Kufa.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Ishaq (704-770), Sirat Rasul Allah, original copy lost but extracts preserved in Ibn Hisham (d. 833), al-Sirat al-Nabawiyyah, and al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari

• Kumayt (d. 743), al-Hashimiyyat

• Malik b. Anas (711-795), Muwatta Imam Malik

• Ibn Sa‘d (784-845), Kitab Tabaqat al-Kubra

• Ahmad b. Hanbal (780-855), Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal

• Muhammad b. Ismail al-Bukhari (810-870), Sahih Bukhari

• Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (821-875), Sahih Muslim

• Al-Masudi (896-956), Muruj al-dhahab wa ma’adin al-jawhar

• Ahmad b. Yahya al-Baladhuri (d. 892), Kitab Futuh al-Buldan; Ansab al-Ashraf

• Ahmad b. Abu Yaqub al-Ya‘qubi (d. 898), Tarikh ibn Wadih

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 533; Arzina R. Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 132-134)

2. Imam al-Husayn ibn ‘Ali (661-680)

God gave preference to Muḥammad before all His creatures. He graced him with prophethood and chose him for His message. After he had warned His servants and informed them of what he had been sent with, God took him for Himself. We are his family (ahlihi), those who possess his authority (awliya’), those who have been made his trustees (awsiya’), and his inheritors (wuratha); we are those who have more right to this position among the people than anyone else.

Imam al-Husayn ibn ‘Ali,

(al-Tabari, The History of al-Tabari, in Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 30)

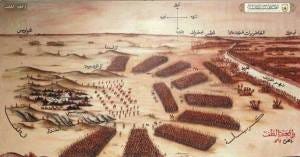

Mu‘awiya openly opposed and fought against the Caliphate of Imam ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib. After the death of Imam ‘Ali, his son Pir Imam al-Hasan succeeded to the Caliphate but – due to the weakness of his support and resources – had to abdicate the Caliphate to Mu‘awiya on the condition that Yazid would not succeed to the Caliphate after him. However, Mu‘awiya ibn Abu Sufyan ensured that his son Yazīd succeeded him as Caliph – an event which directly contradicted the agreement that Pir Imam al-Hasan had made with Mu‘awiya earlier. Unlike Mu‘awiya, who was unrighteous but tried to keep the appearance of dignity to the Caliphate, Yazid was an open sinner and disgraced the position by his drinking of wine and many other sinful activities. When Yazid succeeded as Caliph, he sought to gain the allegiance of Imam al-Husayn to legitimize his succession but the Imam refused to do so. Meanwhile, the people of Kufa invited Imam al-Husayn to lead them.

The Imam and his close family and companions were journeying from Makkah to Kufa and were intercepted by the Umayyad armies sent by Yazid and surrounded at the plains of Karbala. After cutting off their water supply for several days, the Umayyad armies engaged the Imam and his supporters in battle. Outnumbered by an army of over twenty thousand men, Imam al-Husayn, his family, and supporters were inhumanly massacred and martyred in what became known as the Battle of Karbala. The dead included the sons of Imām al-Ḥusayn – among them a six month old infant ‘Ali Asghar, the sons of Imam ‘Ali ibn Abu Talib, and the children of Imam al-Hasan. The only surviving male member of the Imam’s family was his son Imam ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin – who was sick during the battle and saved from execution due to the intervention of Hazrat Zaynab – the sister of Imam al-Husayn.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Ishaq (704-770), Sirat Rasul Allah, original copy lost but extracts preserved in Ibn Hisham (d. 833), al-Sirat al-Nabawiyyah, and al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari

• Abu Miknaf (d. 774), Kitab Maqtal al-Husayn

• Malik b. Anas (711-795), Muwatta Imam Malik

• Ibn Sa‘d (784-845), Kitab Tabaqat al-Kubra

• Ahmad b. Hanbal (780-855), Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal

• Muhammad b. Ismail al-Bukhari (810-870), Sahih Bukhari

• Muslim b. al-Hajjaj (821-875), Sahih Muslim

• Al-Masudi (896-956), Muruj al-dhahab wa ma’adin al-jawhar

• Ahmad b. Yahya al-Baladhuri (d. 892), Kitab Futuh al-Buldan; Ansab al-Ashraf

• Ahmad b. Abu Yaqub al-Ya‘qubi (d. 898), Tarikh ibn Wadih

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 533; Arzina R. Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 132-136)

3. Imam ‘Ali b. al-Husayn Zayn al-‘Abidin (680-713)

It is because of us, the initiated Guides

That the sky does not come crashing down to earth,

That the beneficent rain falls from the sky

That mercy is spread…

The earth will engulf its inhabitants

If one of us is not upon it.Imam ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin,

(Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, The Divine Guide in Early Sh‘ism, 61)

Imam ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin was the only surviving male member of Imam al-Husayn’s family at Karbala. Imam Zayn al-‘Abidin lived a low-key life and stayed out of politics. He was exempt from giving allegiance to Yazid and stayed with his family in Madinah. On one occasion, this Imam went to Makkah for pilgrimage. The Ummayad prince Hisham ibn ‘Abd al-Malik was also present and he was unable to perform the circumambulation of the Ka‘bah due to the large crowd. However, when the crowd saw Imam Zayn al-‘Abidin approach, they saw his face – recognizing the light and aura of the Prophet and Mawlana ‘Ali – and respectfully moved out of the way so the Imam could walk toward the Ka‘bah. On seeing this, one of Hisham’s companions exclaimed, “who is this man?” Hisham denied knowing who the Imam was, and on that occasion the poet al-Farazdaq approached and recited the following poem on the spot:

This is the son of Husayn and the grandson of Fatimah the daughter of the Apostle through whom the darkness dispersed.

This is he whose ability the valley (of Mecca) recognizes, He is known by the (Sacred) House and the Holy sanctuary and the lands outside the sanctuary.

This is the son of the best of God”s servants.– Al-Farazdaq, (Diwan al-Farazdaq, Read the Entire Poem at Ballandalus)/p>

Imam ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin was also known for being in continuous prayer and he composed a series of spiritual prayers called al-Sahifah al-Sajjadiyyah. The prayers in this text also speak to the concept of Imamat, such as the supplication below:

O God, surely Thou hast confirmed Thy religion in all times with an Imam whom Thou hast set up as a guidepost to Thy servants and lighthouse in Thy lands, after his cord has been joined to Thy cord! Thou hast appointed him the means to Thy good pleasure, made obeying him obligatory, cautioned against disobeying him, and commanded following his commands, abandoning his prohibitions, and that no forward-goer go ahead of him or back-keeper keep back from him!

Imam Zayn al-‘Abidin, (al-Sahifah al-Sajjadiyyah, Read Here)

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin (d. 713), al-Sahifah al-Sajjadiyyah al-Kamilah

• Al-Farazdaq (d. 730), Diwan al-Farazdaq

• Abu Miknaf (d. 774), Kitab Maqtal al-Husayn

• Ibn Sa‘d (784-845), Kitab Tabaqat al-Kubra

• Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (821-875), Rijal ‘Urwa b. al-Zubayr

• Ahmad b. Yahya al-Baladhuri (d. 892), Kitab Futuh al-Buldan; Ansab al-Ashraf

• Ahmad b. Abu Yaqub al-Ya‘qubi (d. 898), Tarikh ibn Wadih

• Al-Mubarrad (826-898), Kitab al-Kamil

• Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Barqi (d. 894), Kitab al-Mahasin

• Al-Saffar al-Qummi (d. 903), Basa’ir al-Darajat

• Sa‘d b. ‘Abdullah al-Qummi (d. 911), al-Maqalat Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• ‘Ali b. Ibrahim al-Qummi (d. 919), Tafsir al-Qummi

• Al-Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti (d. before 922), Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni (d. 941), Usul al-Kafi

• Al-Masudi (896-956), Muruj al-Dhahab wa Ma‘adin al-Jawhar

• Abu Amr Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Kashshi (d. 961), Rijal al-Kashshi (Ikhtiyar ma‘rifat al-rijal)

• Ja‘far b. Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Sara’ir wa Asrar al-Nutuqa

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Da’aim al-Islam; Sharh al-Akhbar

• Al-Mufid (d. 1022), Kitab al-Irshad

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 540; Arzina R. Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 132-136)

4. Imam Muhammad al-Baqir (713-743)

We are the hujjah (proof) of God and His Gate. We are the tongue as well as the Face of God; we are the Eyes of God [guarding] His creation and we are the Guardians of the Divine Command (wulat al-amr) on earth.

Imam Muhammad al-Baqir,

(Arzina R. Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 83)

On the death of Imam Zayn al-‘Abidin, he was succeeded by Imam Muhammad al-Baqir. Imam al-Baqir was known as “Baqir al-‘Ilm” – the one who splits open knowledge – because of his deep spiritual and religious knowledge. In al-Baqir’s time, there were many other claimants to the Imamat from other Shi‘i groups – including the Hasanid line, the ‘Abbasid line, and the descendants of Muhammad b. al-Hanafiyyah (a third, non-Fatimid son of Imam ‘Ali). In the midst of these counter-claimants to authority, Imam al-Baqir taught the key concepts of the formalized doctrine of Imamat: the concept of nass (designation of one Imam by the prior Imam), which Imam al-Baqir used to prove his own Imamat against the counter-claimants; the concept of ‘ilm (spiritual knowledge) that each Imam must possess to be the Imam; the Holy Spirit (ruh al-qudus) which is the spiritual inspiration by which God guides and supports the intellect and soul of the Imam; the concept of nur (light), which is the original form of the Imams’ existence before the creation of the world and which is spiritually manifest in the soul of every Imam; and the concept of ‘ismah (protection) which means the true Imam is protected by God from committing sins and errors. Imam al-Baqir was also highly respected in Sunni Muslim scholarly circles and many Sunni hadith narrators transmitted hadiths from al-Baqir: “The evidence suggests that al-Baqir’s position among his contemporaries was such that many scholars felt inferior to him; even the most eminent regarded him with awe and reverence on account of his outstanding knowledge” (Arzina Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 96). Imam al-Baqir provided commentaries on the verses of the Holy Qur’an about various subjects including tawhid and Imamat, through which he showed how the Qur’an in numerous places testifies to the authority of the hereditary Imams. Imam al-Baqir also gave many esoteric and spiritual teachings on metaphysics and cosmology. Imam al-Baqir would often travel in scholarly circles with his son, Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri (d. 741), in Abu al-Hajjaj Yusuf al-Mizzi (d. 743), Tahdib al-Kamal

• Kumayt (680-745), Hashimiyyat

• Malik b. Anas (711-795), Muwatta Imam Malik

• Ibn Sa‘d (784-845), Kitab Tabaqat al-Kubra

• Ahmad b. Hanbal (780-855), Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal

• Ahmad b. Yahya al-Baladhuri (d. 892), Kitab Futuh al-Buldan; Ansab al-Ashraf

• Ahmad b. Abu Yaqub Al-Ya‘qubi (d. 898), Tarikh ibn Wadih

• Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Barqi (d. 894), Kitab al-Mahasin

• Al-Saffar al-Qummi (d. 903), Basa’ir al-Darajat

• Sa‘d b. ‘Abdullah al-Qummi (d. 911), al-Maqalat Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• ‘Ali b. Ibrahim al-Qummi (d. 919), Tafsir al-Qummi

• Al-Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti (d. before 922), Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni (d. 941), Usul al-Kafi

• Al-Masudi (896-956), Muruj al-Dhahab wa Ma‘adin al-Jawhar

• Abu Amr Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Kashshi (d. 961), Rijal al-Kashshi (Ikhtiyar ma‘rifat al-rijal)

• Ja‘far b. Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Sara’ir wa Asrar al-Nutuqa

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Da’aim al-Islam; Sharh al-Akhbar

• Al-Mufid (d. 1022), Kitab al-Irshad

• ‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), Kitab al-Milal wa’l-Nihal

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Ibn Hajar (d. 1449), Tahdib al-Tahdib

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 536-39 Arzina R. Lalani, Early Shi‘i Thought, 136-166)

5. Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq (743-765)

He who knows us knows God, and he who does not know us does not know God. It is because of us that God is known and because of us that He is worshipped. Without God, we would not be known, and without us, God would not be known.

Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq,

(Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, The Divine Guide in Early Shi‘ism, 46)

Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq succeeded his father Imam Muhammad al-Baqir to the Imamat. The first twenty-years of Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq’s Imamat saw a number of key events including the revolt of his uncle Zayd and the ‘Abbasid overthrow of the ‘Umayyads. Even when the new ‘Abbasid revolution had succeeded, the ‘Abbasids offered the caliphate to Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq and he rejected it, as he did not want to be a mere puppet. However, in due time, the ‘Abbasid Caliphs became hostile to the Imam and his family and saw the Shi‘i Imams as their rivals. Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq devoted much of his time to teaching and acquired a following of some of the best minds of his time. The Imam continued to systematize and consolidate the Imamat doctrine taught by Imam al-Baqir – including the concepts of taqiyyah, zahir and batin, nass, ‘ismah, nur, etc. Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq gained more prominence in the last ten years of his life because many of the ‘Alid counter-claimants had been killed and their movements wiped out. Most of the Shi‘ah began to rally around Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq, including a diverse group of thinkers such as the famous alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan. Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq was also revered in Sunni circles – he was in fact the teacher of Abu Hanifa and Malik ibn Anas – the two scholars whom the Hanafi and Maliki schools of Sunni law are named after. The Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq also stressed how the Imam’s knowledge and role was spiritual and not political, due to the ‘ilm and the Holy Spirit that inspired the Imam’s thoughts and deeds. He also stressed the importance of taqiyyah – of concealing one’s faith and beliefs when in danger and of the importance of keeping the batin hidden from the unworthy. Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq designated his elder son Isma‘il as his successor to the Imamat and died in 765 – according to some reports, the Imam was poisoned on the ‘Abbasid Caliph’s orders.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Malik b. Anas (711-795), Muwatta Imam Malik

• Ibn Sa‘d (784-845), Kitab Tabaqat al-Kubra

• Ahmad b. Hanbal (780-855), Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal

• Ahmad b. Yahya al-Baladhuri (d. 892), Kitab Futuh al-Buldan; Ansab al-Ashraf

• Ahmad b. Muhammad al-Barqi (d. 894), Kitab al-Mahasin

• Ahmad b. Abu Yaqub al-Ya‘qubi (d. 898), Tarikh ibn Wadih

• Al-Saffar al-Qummi (d. 903), Basa’ir al-Darajat

• Sa‘d b. ‘Abdullah al-Qummi (d. 911), al-Maqalat Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• ‘Ali b. Ibrahim al-Qummi (d. 919), Tafsir al-Qummi

• Al-Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti (d. before 922), Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Abu’l-Hasan al-Ash‘ari (847-936), Maqlat al-Islamiyin

• Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni (d. 941), Usul al-Kafi

• Al-Masudi (896-956), Muruj al-Dhahab wa Ma‘adin al-Jawhar

• Abu Amr Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Kashshi (d. 961), Rijal al-Kashshi (Ikhtiyar ma‘rifat al-rijal)

• Ja‘far b. Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Sara’ir wa Asrar al-Nutuqa

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Da’aim al-Islam; Sharh al-Akhbar

• Al-Mufid (d. 1022), Kitab al-Irshad

• ‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), Kitab al-Milal wa’l-Nihal

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Ibn Hajar (d. 1449), Tahdib al-Tahdib

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 543-545)

6. Imam Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far (765-ca. 775)

We narrate [the tradition] and you narrate [the tradition] that when Isma‘il the son of the Imam Ja‘far completed seven years of age, the Master (sahib) of the Time (waqt) declared him the Master of Religion (sahib al-din) and his heir apparent among sons. And he guarded him from his other of his sons, kept him away from the contact with the public, and his education went on under his own supervision.

Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman [d. 960], (Asrar al-Nutuqa, tr. Ivanow in Ismaili Tradition Concerning the Rise of the Fatimids, 296)

Imam Isma‘il was one of the two elder sons of Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq born of his first wife Fatimah, the granddaughter of Imam al-Hasan. Isma‘il was born between 699-702 and his full-brother was ‘Abdullah. On several occasions, Isma‘il acted as the head of the family in the absence of his father Imam al-Sadiq to protest the killing of one of the Imam’s followers. Some sources, mainly Twelver texts, report that Isma‘il passed away during the lifetime of Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq – but those same sources also report that Isma‘il was seen several days later in Basra, suggesting that he did not really die but was sent away out of Madinah. But the majority of sources – Sunni, Twelver, and Ismaili – agree that Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq appointed and designated Isma‘il as the next Imam (as documented here).

According to the majority of the available sources, he [Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq] had designated his second son Isma‘il (the eponym of the Isma‘iliyya) as his successor, by the rule of the nass. There can be no doubt about the authenticity of this designation, which forms the basis of the claims of the Isma‘iliyya and which should have settled the question of al-Sadiq’s succession in due course.

Farhad Daftary, (The Isma‘ilis: Their History and Doctrines, 88)

However, because Isma‘il was absent from Madinah when Imam Ja‘far passed away, the Shi‘a split into numerous groups, with the majority first following his brother ‘Abdullah, and then later following his half-brother Musa al-Kazim. Meanwhile, the minority continued to follow the Imamat of Isma‘il and his descendants. This latter group became known as the Ismailis.

Our branch of Shia Islam, in that particular generation of the family, accepted the legitimacy of the eldest son, Isma‘il, as being the appointed Imam to succeed and that is why they are known as Ismailis. And that branch of the family has continued today hereditarily and that is why there is a living Imam for the Ismaili Muslims.

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,

(CBC Man Alive Interview, October 8, 1986, Read at NanoWisdoms)

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Sa‘d b. ‘Abdullah al-Qummi (d. 911), al-Maqalat Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Ibn al-Haytham (d. after 909), Kitab al-Munazarat

• Al-Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti (d. before 922), Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismailis of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Abu’l-Hasan al-Ash‘ari (847-936), Maqlat al-Islamiyin

• Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni (d. 941), Usul al-Kafi

• Abu Amr Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Kashshi (d. 961), Rijal al-Kashshi (Ikhtiyar ma‘rifat al-rijal)

• Ja‘far b. Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Sara’ir wa Asrar al-Nutuqa

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Da’aim al-Islam; Sharh al-Akhbar

• Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijstani (d. after 971), Sullam Najat; Ithbat al-Nabuwwat

• Ibn Babawayh (d. 991), Kitab al-Tawhid; Kamal al-Din

• Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani, al-Masabih fi Ithbat al-Imamah

• Al-Mufid (d. 1022), Kitab al-Irshad

• Ahmad b. ‘Ali al-Najashi (d. 1058), Kitab al-Rijal

• Hatim b. Imran b. Zuhra (d. 1104), al-Usul wa’l-Ahkam

• ‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), Kitab al-Milal wa’l-Nihal

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 546-548)

7. Imam Muhammad b. Isma‘il (775-ca.806)

Then came Muhammad b. Isma‘il by the command of God and His Inspiration of him. His da‘is dispersed, travelling in different provinces (jaza’ir), and ordering the local people to carry on the da‘wah in his favour. The world became alive with his da‘wah and his influence spread.

Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman, (Asrar al-Nutuqa, tr. Ivanow in Ismaili Tradition Concerning the Rise of the Fatimids, 297)

Imam Muhammad b. Isma‘il was the eldest son of Imam Isma‘il and also the eldest grandson of Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq. After the death of ‘Abdullah, Muhammad was the senior most member of this Fatimid branch of al-Husayn’s descendants. However, due to the rival group that recognized Musa al-Kazim and the ‘Abbasid persecution of all Fatimids, Imam Muhammad b. Isma‘il fled Madinah with his sons for the east. For this reason, Muhammad b. Isma‘il was known as al-Maktum (the veiled one). Different sources report that Imam Muhammad and his sons first went to Iraq and then to Khuzistan in southwestern Persia. Imam Muhammad b. Isma‘il had two sons when living in Madinah and then four more sons after his emigration, among whom was his successor Imam ‘Abdullah al-Wafi.

Thenceforward the story of the Ismailis, of my ancestors and their followers, moves through all the complexities, the ebb and flow, of Islamic history through many centuries…there is, however, endless fascination in the study of the web of characters and of events, woven across the ages, which unites us in this present time with all these far-distant glories, tragedies and mysteries. Often persecuted and oppressed, the faith of my ancestors was never destroyed; at times it flourished as in the epoch of the Fatimite Khalifs, at times it was obscure and little understood.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III,

(Memoirs of the Aga Khan: World Enough and Time, 1954, Read at NanoWisdoms)

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Sa‘d b. ‘Abdullah al-Qummi (d. 911), al-Maqalat Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Ibn al-Haytham (d. after 909), Kitab al-Munazarat

• Al-Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti (d. before 922), Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismaili Community of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Abu’l-Hasan al-Ash‘ari (847-936), Maqlat al-Islamiyin

• Muhammad b. Ya‘qub al-Kulayni (d. 941), Usul al-Kafi

• Abu Amr Muhammad b. ‘Umar al-Kashshi (d. 961), Rijal al-Kashshi (Ikhtiyar ma‘rifat al-rijal)

• Ja‘far b. Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Sara’ir wa Asrar al-Nutuqa

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Da’aim al-Islam; Sharh al-Akhbar

• Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijstani (d. after 971), Sullam Najat; Ithbat al-Nabuwwat

• Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani, al-Masabih fi Ithbat al-Imamah

• Al-Mufid (d. 1022), Kitab al-Irshad

• Ahmad b. ‘Ali al-Najashi (d. 1058), Kitab al-Rijal

• Hatim b. Imran b. Zuhra (d. 1104), al-Usul wa’l-Ahkam

• ‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), Kitab al-Milal wa’l-Nihal

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 550-551)

2. The Pre-Fatimid (First) Period of Concealment (Dawr al-Satr)

Those people (the concealed Ismaili Imams) were constantly on the move because of the suspicions various governments had concerning them. They were kept under observation by the tyrants, because their partisans were numerous and their propaganda had spread far and wide. Time after time they had to leave the places where they had settled. Their men, therefore, took refuge in hiding, and their (identity) was hardly known, as (the poet) says: If you would ask the days what my name is, they would not know, And where I am, they would not know where I am.

Ibn Khaldun, (Sunni Historian, Muqaddimah, tr. Frank Rosenthall, Read Here)

8. Imam ‘Abdullah ibn Muhammad al-Wafi (ca. 806-828)

The lives of the next three Imams are generally shrouded in mystery because they were constantly fleeing persecution by the ‘Abbasid Caliphs and their agents. Imam ‘Abdullah succeeded his father Imam Muhammad and traveled throughout Persia and the Middle East. He did not reveal his true identity publicly and only a few high ranking Ismaili hujjats and da‘is were aware of his whereabouts. Imam ‘Abdullah was known by the surnames al-Radi and al-Wafi, along with several other names. During this period, the Imam guided the Ismailis through a vast underground da‘wah network and the da‘is simply referred to the Imam of the time by the name “Muhammad b. Isma‘il” to trick their enemies into searching for the seventh Imam who had already died and to conceal the true Imam’s identity. Imam ‘Abdullah’s life story is reported mainly in the book Istitar al-Imam by Ahmad al-Naysaburi and later by Idris Imad al-Din. However, many non-Ismaili authors like Ibn Rizam, Akhu Muhsin, and Tabari also report his activities. According to these various sources, Imam ‘Abdullah first went to Askar Mukram in Khuzistan where he posed as a Hashimite ‘Aqilid merchant. Later he fled to Basra and then settled in Salamiyya where he set up the headquarters of the Imamat and the da‘wah. Imam ‘Abdullah designated his son Ahmad (known also as Taqi Muhammad) as his successor and died around 828. For more on Salamiyyah as the headquarters of the Ismaili Imams, see the article by Nimira Dewji, here.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Sa‘d b. ‘Abdullah al-Qummi (d. 911), al-Maqalat Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Ibn al-Haytham (d. after 909), Kitab al-Munazarat

• Al-Hasan b. Musa al-Nawbakhti (d. before 922), Firaq al-Shi‘ah

• Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismaili Community of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi, (d. 934), Letters preserved in Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Ibn Rizam (first-half of 10th century), Kitab Radd ‘ala’l-Isma‘iliyyah, preserved in later sources

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Urjuza al-mukhtara; Majalis al-Musarat

• Akhu Muhsin (d. 982), excerpts preserved in al-Nuwayri (d. 1333), Ibn Dawadari (d. 1335), and al-Maqrizi (d. 1442)

• Ahmad b. Ibrahim al-Naysaburi (late tenth century), Istitar al-Imam

• Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani (d. after 1021), al-Risalat al-Wa‘za

• Hatim b. Imran b. Zuhra (d. 1104), al-Usul wa’l-Ahkam

• ‘Abd al-Karim al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), Kitab al-Milal wa’l-Nihal

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• l-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 551-557)

9. Imam Ahmad ibn ‘Abdullah al-Taqi (828-ca. 870)

Imam Ahmad (Taqi Muhammad) lived mainly in Salamiyya and oversaw a resurgence in the Ismaili da‘wah during his Imamat. While not much is known about his life activities, various Ismaili and non-Ismaili sources mention him as the leader of the Ismaili movement after Imam ‘Abdullah.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman (d. 914), Sirat Ibn Hawshab, fragments survive in later Fatimid literature.

• Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman (d. 914), Kitab al-Kashf, compiled by Ja‘far ibn Mansur (d. 960)

• Ja‘far al-Hajib (Imam al-Mahdi’s servant in late-ninth century – early tenth century), Sirat Ja‘far (Memoirs)

• Ibn Rizam (first-half of 10th century), Kitab Radd ‘ala’l-Isma‘iliyyah, preserved in later sources

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismaili Community of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi, (d. 934), Letters preserved in Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Anonymous Fatimid author, Sirat Imam al-Mahdi, written in mid-tenth century

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Urjuza al-mukhtara; Majalis al-Musarat

• Akhu Muhsin (d. 982), excerpts preserved in al-Nuwayri (d. 1333), Ibn Dawadari (d. 1335), and al-Maqrizi (d. 142)

• Ahmad b. Ibrahim al-Naysaburi (late tenth century), Istitar al-Imam

• Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani (d. after 1021), al-Risalat al-Wa‘zah

• Hatim b. Imran b. Zuhra (d. 1104), al-Usul wa’l-Ahkam

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 551-557)

10. Imam al-Husayn ibn Ahmad al-Radi (ca. 870-ca. 880-81)

Imam al-Husayn b. Ahmad, known as Radi al-Din ‘Abdullah, led the Ismaili da‘wah for a very short period in which it started achieving success in various parts of ‘Abbasid territory. Before he passed away, the Imam entrusted the care of his son and successor, ‘Abdullah ‘Ali al-Mahdi who was then around 7 years old to his full brother, Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Shalagha. While Imam al-Mahdi was growing up, Muhammad b. Ahmad served as his Trustee (mustawda) and directed the Ismaili da‘wah for some years.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman (d. 914), Sirat Ibn Hawshab, fragments survive in later Fatimid literature.

• Ja‘far al-Hajib (Imam al-Mahdi’s servant in late-ninth century – early tenth century), Sirat Ja‘far (Memoirs)

• Ibn Rizam (first-half of 10th century), Kitab Radd ‘ala’l-Isma‘iliyyah, preserved in later sources

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismaili Community of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi, (d. 934), Letters preserved in Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari; Tafsir al-Tabari

• Anonymous Fatimid author, Sirat Imam al-Mahdi, written in mid-tenth century

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Urjuza al-mukhtara; Majalis al-Musarat

• Akhu Muhsin (d. 982), excerpts preserved in al-Nuwayri (d. 1333), Ibn Dawadari (d. 1335), and al-Maqrizi (d. 1442)

• Ahmad b. Ibrahim al-Naysaburi (late tenth century), Istitar al-Imam

• Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani (d. after 1021), al-Risalat al-Wa‘zah

• Hatim b. Imran b. Zuhra (d. 1104), al-Usul wa’l-Ahkam

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 551-557)

3. The Fatimid Period of the Imam-Caliphs:

Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,

(Restored Monuments in Darb al-Ahmar Address, October 26, 2007, Read at NanoWisdoms)

The Fatimid period is one of the best documented periods in Islamic history. As noted, almost the entire corpus of the histories of the Fatimid dynasty and Fatimid Egypt, written in the time of the Fatimids themselves, did not survive directly. This material was, however, at least partially preserved by later authorities, especially by the Mamluk historian al-Maqrizi (d. 845/1442), who produced the most extensive account of the Fatimids in several of his works. Indeed, many medieval Muslim historians and chroniclers wrote about the Fatimids, who are also discussed in the universal histories of Miskawayh (d. 421/1030) and Ibn al-Athir (d. 630/1233), amongst many others, as well as in a variety of regional histories of Egypt and Syria. (Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 139)

Before the rise of the Fatimids with Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi, the Ismaili Imams lived in concealment from the public. This allowed pro-‘Abbasid Sunni Muslim polemicists such as Ibn Rizam, Akhu Muhsin, and the ‘Abbasids themselves to pen numerous lies and slanders about the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs. However, a large number of Egyptian, North African, Persian, and Arab Muslim scholars in history recognized the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs as genuine and legitimate descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, Imam ‘Ali, and Hazrat Fatimah through the lineage of Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq. For example, the prominent Twelver Shi‘i scholar and genealogist, Shariff al-Radi (d. 1015), who was himself a descendant of Imam ‘Ali, declared in a poem before the ‘Abbasid Court that Imam al-Hakim bi Amr Allah was the legitimate descendant of Prophet Muhammad and Imam ‘Ali. To quote al-Radi’s own poem from his Diwan:

Why am I treated with contempt when I have

A sharp tongue and a fierce disposition?

Am I subjected to injustice in the land of the enemy

While in Egypt is the ‘Alid Caliph?

His ancestors are also mine and his master is mine but

The great distance treats me with injustice;

My roots are intertwined with his: the lords of

All people, [Prophet] Muhammad and [Imam] ‘Ali.– Sharif al-Radi (Twelver Shi‘i scholar and ‘Alid genealogist)

(Diwan, Beirut, 1309 A.H., 972; tr. Idris El-Hareir, Ravene MBaye, The Spread of Islam throughout the World, 252)

The following non-Ismaili Muslim scholars, historians and theologians recognize the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs as direct legitimate descendants of Imam ‘Ali b. Abi Talib through Imam Ja‘far al-Sadiq:

• ‘Adud al-Dawla (Buyid Amir) (944-983), Letter to Imam al-‘Aziz in which the Bu’yid Amir addresses the Fatimid Caliphs as “al-Hazrat al-Sharifah,” preserved in Ibn Taghri Birdi (1410-1470), al-Nujum al-Zahirah fi Muluk Misr wa’l-Qahirah

• Ibn al-Jazzar (d. ca. 1004), Kitab Akhbar al-Dawlah

• Sharifs of Egypt and Hijaz (late 10th century), as reported in several historical chronicles including al-Maqrizi

• Sharif al-Radi, Diwan (Poetry, quoted above) (d. 1015), also reported by Ibn Athir.

• Ibn al-Raqiq (d. 1027), Tarikh Ifriqiyya wa’l-Maghrib

• Ibn Miskawayh, (d. 1030), Tajarib al-Umam

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh: “He himself and his partisans who declare his Imamate hold that his lineage is authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) according to what we mentioned. Many among the ‘Alid scholars of genealogy are also in agreement with them. This statement that al-Sharīf al-Raḍī uttered bears witness to its authenticity” (al-Kamil, vol. 6, 446)

• Ibn Zafir (d. 1216), Akhbar al-Duwwal al-Munqati‘a

• Ibn Hammad (1153-1230), Akhbar muluk Bani ‘Ubayd wa siratuhum

• Ibn al-Tuwayr (d. 1220), reported in Maqrizi, Itti‘az al-Hunafa and Ibn al-Zayyat (15th century), Al-Kawakib al-Sayyarah fi Tartib al-Ziyarah

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Muhyi al-Din b. ‘Abd al-Zahir (d. 1292), al-Rawdah al-Zahirah fi Khitat al-Mu’izziyyah al-Qahirah

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Itti‘az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

(See Abu Izzedin, History of Druzes; Walker, al-Maqrizi and the Fatimids; Shainool Jiwa, “Fatimid-Buyid Diplomacy during the reign of al-Aziz bi’llah”; Maqrizi, tr. Shainool Jiwa, Towards a Shi‘i Mediterranean Empire; Prince P. H. Mamour, Polemics on the Origins of the Fatimi Caliphs)

11. Imam ‘Ali b. al-Husayni Abu Muhammad ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi bi’llah (881-934)

In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. We seek His Help. From the Servant of God, Abu Muhammad al-Imam al-Mahdi bi-illah, Commander of the Faithful, to his followers among the faithful and all the Muslims. Peace be with you. The Commander of the Faithful praises God before you. There is no god except Him… Therefore praise God who has let you attain the time of the Commander of the Faithful, and distinguished you with the blessing of his reign and good fortune of his dominion. May your hopes be high and your optimism grow with confidence in his justice.

Imam ‘Abdullah Muhammad al-Mahdi,

(Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man, Iftah al-Da‘wah, tr. Hamid Haji, Founding the Fatimid State, 207-208)

Imam Abu Muhammad ‘Ali b. al-Husayn ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi was born in 873 in Askar-i Mukram. His father, the previous Imam, died when he was 7 years old and the affairs of the Ismaili da‘wah were entrusted to al-Mahdi’s paternal uncle, Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Shalagha, for about 20 years. Al-Mahdi then married the daughter of his paternal uncle, who gave birth to his son and successor, Imam Abu’l-Qasim Muhammad al-Qa’im bi-amr Allah. According to the Sirat Ja‘far, the memoirs of al-Mahdi’s chamberlain, al-Mahdi lived in Salamiyyah and was known as a wealthy noble person. There was a secret underground passage under the Imam’s residence through which Ismaili da‘is came and went safely.

When the Abbasid began their manhunt for the Ismaili Imams, Imam al-Mahdi and his partisans were forced to move out of Salamiyyah. One Ismaili da‘i, al-Husayn b. Zikrawayh, who was captured by the ‘Abbasids and “interrogated under torture,” revealed Imam al-Mahdi’s identity and whereabouts. This allowed the Abbasids to intensify and expand their chase for the Imam. In 904, starting in Syria, Imam al-Mahdi traveled to Palestine and then, after the ‘Abbasids executed his dais, to Egypt. However, when the Abbasid army once again advanced on Imam al-Mahdi’s location, he was forced to relocate again. While many of the Imam’s companions expected him to move to Yemen, Imam al-Mahdi instead traveled deeper into North Africa to avoid potential military conflicts with the ‘Abbasids. Not surprisingly, North Africa was also not safe for the Imams, after the Sunni Aghlabids ruling North Africa, were instructed by their ‘Abbasid overlords to search for the Ismaili Imam and his companions. Still under the disguise of merchants, Imam al-Mahdi, his brother Ja‘far, and son, the future Imam al-Qa’im, took refuge on the far west coast of Africa in Morocco. One of the head da‘is of the Isma’ili da‘wah in North Africa during this time was Abu ‘Abdullah al-Shi‘i. Still in contact with Imam al-Mahdi, it was Abu ‘Abdullah al-Shi‘i who was largely responsible for establishing the base of the Fatimid Caliphate. This Ismaili da‘i had targeted his instruction towards the warlike Berber clans of North Africa, slowly getting them to pledge allegiance to the Imam. Using these new forces, the Ismaili da‘īs overthrew various amirs in North Africa, including the Aghlabid Amir, clearing the way for the Imam to establish the dawlat al-ḥaqq or the “the kingdom of the truth.” After years of warfare, al-Shi‘i minted new coins heralding the arrival of the hujjat Allah or “proof of God”, and escorted the Ismaili Imam and his family from Morocco to Raqqada with the Berber army. Raqqada became the new capital of the young Fatimid State. Upon meeting and seeing the Imam, his Mawla, al-Shi‘i was “bathed in tears” and reaffirmed his bay‘ah. The following day, in his tent, the Imam granted an audience to each and every individual troop member who also pledged their bay‘ah. Then on Friday January 5th, 910 CE, Imam al-Mahdi was declared the “Commander of the Faithful” and the first Caliph of the newly found Fatimid Caliphate and his opening message (quoted above) was sent to all the local towns. An Ismaili eyewitness, the da‘i Ibn al-Haytham, recounts the arrival of the Imam to his new North-African kingdom meeting with the two da‘is Abu ‘Abdullah and Abu’l-‘Abbas:

It was he whose excellence could not be hidden and ‘the truth has now arrived and falsehood has perished’ [Qur’an 17.81]. The stars declined and the Alive and Self-subsistent appeared. Abu-‘l-‘Abbas went out and we went out with him and met the lord on the mountain pass of Sabiba. I cannot forget his auspicious appearance, the splendor of his light, the brightness of his face, the elevation of his rank, the perfection of his build, and the resplendent beauty in his dawn. If I were to say that the lights that shine were created from the surplus of his light, I would have voiced the truth and the manifest reality. Abu’l-‘Abbas dismounted before him, may the blessings of God be upon him, and kissed the earth. He lay on the ground in front of him, and his brother Abu ‘Abdallah dismounted for him, as did all of the friends from the Kutama and the others of their followers. No one was left riding except the Commander of the Faithful, may the blessings of God be upon him, the sun most radiant, and [his son] the shining moon and glittering light, Abu’l-Qasim [Imam al-Qa’im]. These two, may the blessings of God be on them both, were the light of the world… The earth began to shine with his light and the world was illuminated by his advent, and the Maghrib excelled because of his presence in it and his having taken possession of it.

Ibn al-Haytham, (Kitab al-Munazarat, tr. Wilfred Madelung & Paul Walker, The Advent of the Fatimids – A Contemporary Shi’i Witness, 167)

For more information on Imam al-Mahdi and the Fatimids, see this article by Nimira Dewji.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman (d. 914), Sirat Ibn Hawshab, fragments survive in later Fatimid literature.

• Ja‘far al-Hajib (Imam al-Mahdi’s servant in late-ninth century – early tenth century), Sirat Ja‘far (Memoirs)

• Ibn Rizam (first-half of 10th century), Kitab Radd ‘ala’l-Isma‘iliyyah, preserved in later sources

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismaili Community of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi, (d. 934), Letters preserved in Abu Ja‘far Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923), Tarikh al-Tabari;

• Ibn al-Haytham (d. mid. 10th century), Kitab al-Munazrat – an eyewitness memoir of al-Mahdi and his son al-Qa’im.

• Anonymous Fatimid author, Sirat Imam al-Mahdi, written in mid-tenth century

• Ustadh Jawdhar (Abu ‘Ali Mansur al-‘Azizi al-Jawdhari) (d. 972), Sirat al-Ustadh Jawdhar

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Urjuza al-mukhtarah; Iftah al-Da‘wah; Sharh al-Akhbar; Majalis al-Musayarat; Da‘a’im al-Islam

• Al-Khushani (d. 981), Kitab Tabaqat ‘ulama Ifriqiyyah

• Akhu Muhsin (d. 982), excerpts preserved in al-Nuwayri (d. 1333), Ibn Dawadari (d. 1335), and al-Maqrizi (d. 1442)

• Ibn al-Jazzar (d. ca. 1004), Kitab Akhbar al-Dawlah

• Ibn al-Raqiq (d. 1027), Tarikh Ifriqiyya wa’l-Maghrib

• Ibn Miskawayh, (d. 1030), Tajarib al-Umam

• Ibn al-Muhadhdhab (fl. mid tenth century), Siyar al-A’immah

• Ahmad b. Ibrahim al-Naysaburi (late tenth century), Istitar al-Imam

• Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani (d. after 1021), al-Risalat al-Wa‘zah

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh

• Ibn Zafir (d. 1216), Akhbar al-Duwwal al-Munqati‘a

• Ibn Muyassar (1231-78), Ta’rikh Misr

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn al-Dawadari (d. 1313), Kanz al-Durar wa jam‘i al-Ghurar

• Al-Marrakushi, (fl. early 14th century), al-Bayan al-Mughrib

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 565-599; Paul Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources, 93-169 for discussion of coins, buildings, inscriptions, letters, eyewitness accounts, and histories about the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs)

12. Imam Abu’l-Qasim Muhammad al-Qa’im bi-amr Allah (934-946)

O people, I reach out to this community of yours just as the Messenger of God, may God bless and keep him, reached out to the Jews and the Christians, who had with them the Torah and the Gospels, churches and synagogues. He, may God bless and keep him, summoned them to the fulfilment of the knowledge that was in the Torah and the Gospels but they would not believe it… In the same way I reach out to this community of yours which has taken your Qurʾan in vain.

Imam al-Qa’im bi-amr Allah,

(‘Id Sermon, April 19, 915, tr. Paul Walker, Orations of the Fatimid Caliphs, 87)

Imam Abu’l-Qasim Muhammad al-Qa’im bi-amr Allah was born in 893 in Salamiyya. He became the Imam in 934 upon the death of his father Imam al-Mahdi. Imam al-Qa’im also travelled with Imam al-Mahdi and received the nass and the title of wali ‘ahd from his father early on. After the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate, Imam al-Qa’im commanded the Fatimid armies and the naval forces. The coastal city of al-Mahdiyya became the main point of operations of the Fatimid navy led by Imam al-Qa’im. The reign of the Imam al-Qa’im was threatened by Abu Yazid’s Khariji revolt in 944-945. With the Berbers swarming quickly to his side, Abu Yazıd launched his revolt against the Fatimids in 943–944. He swiftly conquered almost all of southern Ifriqiya, seizing Qayrawan in Safar 333/October 944. Subsequently in Jumada I 333/January 945, the rebels began their siege of Mahdiyya, where al-Qa’im was now staying. But Mahdiyya put up a vigorous resistance for almost a year, repelling Abu Yazid’s repeated attempts to storm the capital and mounting its own counter-offensive, aided by the new reinforcements sent by Ziri b. Manad, the amir of the Sanhaja (Daftary, The Ismailis, 146). The Imam al-Qa’im died in 946 while the Fatimid armies, led by his son and successor Imam al-Mansur bi’llah (946-953), were fighting the Khariji rebellion. It was as the head of the Fatimid army in the midst of a military victory over the rebels that the Imam al-Mansur disclosed his father’s death and assumed the role of the Imamat as the new Imam of the time.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn Hawshab Mansur al-Yaman (d. 914), Sirat Ibn Hawshab, fragments survive in later Fatimid literature.

• Ja‘far al-Hajib (Imam al-Mahdi’s servant in late-ninth century – early tenth century), Sirat Ja‘far (Memoirs)

• Ibn Rizam (first-half of 10th century), Kitab Radd ‘ala’l-Isma‘iliyyah, preserved in later sources

• Imam ‘Abdullah al-Mahdi (d. 934), Letter to the Ismaili Community of Yemen, in Ja‘far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 960), Kitab al-Fara’id wa Hudud al-Din

• Anonymous Fatimid author, Sirat Imam al-Mahdi, written in mid-tenth century

• Ibn al-Haytham (d. mid. 10th century), Kitab al-Munazrat – an eyewitness memoir of al-Mahdi and his son al-Qa’im.

• Ibn al-Muhadhdhab (fl. mid tenth century), Siyar al-A’immah

• Ustadh Jawdhar (Abu ‘Ali Mansur al-‘Azizi al-Jawdhari) (d. 972), Sirat al-Ustadh Jawdhar

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Urjuza al-mukhtarah; Iftah al-Da‘wah; Sharh al-Akhbar; Majalis al-Musayarat; Da‘a’im al-Islam

• Akhu Muhsin (d. 982), excerpts preserved in al-Nuwayri (d. 1333), Ibn Dawadari (d. 1335), and al-Maqrizi (d. 1442)

• Ibn al-Jazzar (d. ca. 1004), Kitab Akhbar al-Dawlah

• Ibn al-Raqiq (d. 1027), Tarikh Ifriqiyya wa’l-Maghrib

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh

• Ibn Zafir (d. 1216), Akhbar al-Duwwal al-Munqati‘a

• Ibn Hammad (1153-1230), Akhbar muluk Bani ‘Ubayd wa siratuhum

• Ibn Muyassar (1231-78), Ta’rikh Misr

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn al-Dawadari (d. 1313), Kanz al-Durar wa jam‘i al-Ghurar

• Al-Marrakushi, (fl. early 14th century), al-Bayan al-Mughrib

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 565-599; Paul Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources, 93-169 for discussion of coins, buildings, inscriptions, letters, eyewitness accounts, and histories about the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs)

13. Imam Isma‘il Abu’l-Tahir al-Mansur bi’llah (946-953)

O God, most certainly I am Your servant and Your friend. On me You have bestowed such favours that I am by You made mighty; You made me superior and thus You made me most generous. You have raised me and made me honoured by what You had me attain of the deputyship (khilāfa) from esteemed forefathers, the imams of right guidance, and You appointed me the flag of religion. You raised me to the imamate of the believers.

Imam al-Mansur bi’llah,

(‘Id Sermon, April 25, 947, tr. Paul Walker, Orations of the Fatimid Caliphs, 105)

Imam Isma‘il Abu’l-Tahir al-Mansur was born in 914 in North Africa (Qayrawan). His first name was Isma‘il – recalling Isma‘il son of Prophet Abraham who is the ancestor of Prophet Muhammad and the Shi‘i Imams and also recalling Isma‘il ibn Ja‘far al-Sadiq, the progenitor of the Ismaili Imams. He was designated as the next Imam by his father Imam al-Qa’im on several occasions. He assumed the position of Imam in 946 while he led the Fatimid armies in resisting the rebellion of Abu Yazid during the siege of al-Mahdiyya. Imam al-Mansur built a new Fatimid capital called Mansuriyyah. He also authored a book called Tathbit al-Imamah (“The Proof of Imamat”) in which the Imam lays out several arguments from the Qur’an and logic to argue the necessity of a living Imam from the progeny of Prophet Muhammad. Below is a quotation from Imam al-Mansur’s book:

[Quoting the Qur’an:] “If they had referred it to the Messenger and the possessors of authority (ulu’l-amr) among them, those of them whose task it is to investigate would have known the matter” (Holy Qur’an 4:83). [Imam al-Mansur said]: this leads us to say: the possessors of authority (ulu’l-amr) among us are the knowledgeable among us. They are our Imams and the Prophet’s vicegerents over us. They are the Ark of Noah. He who boards it is saved. God has ordered us to follow them and to acquire knowledge from them… Our Prophet Muhammad (God’s blessing be in him) told us that they would not depart from his Book until they come to him together at the Paradiscal Pool and that as long as we cling to them we will never go astray.

Imam al-Mansur bi’llah,

(Tathbit al-Imamah, tr. Sami Makarem, The Shi‘i Imamate, 65)

Imam al-Mansur died in 953 “after having reasserted the Fatimid domination in North Africa and Sicily” (Daftary, The Ismailis, 147) and was succeeded by Imam al-Mu‘izz who had been designated as his successor on several occasions.

Historical Sources mentioning this Imam:

• Ibn al-Muhadhdhab (fl. mid tenth century), Siyar al-A’immah

• Ustadh Jawdhar (Abu ‘Ali Mansur al-‘Azizi al-Jawdhari) (d. 972), Sirat al-Ustadh Jawdhar

• Abu Hanifah al-Nu‘man (d. 974), Urjuza al-mukhtarah; Iftah al-Da‘wah; Shah al-Akhbar; Majalis al-Musayarat; Da‘a’im al-Islam

• Ibn al-Jazzar (d. ca. 1004), Kitab Akhbar al-Dawlah

• Ibn al-Raqiq (d. 1027), Tarikh Ifriqiyya wa’l-Maghrib

• Ibn Athir (1160-1233), al-Kamil fi’l-Tarikh

• Ibn Zafir (d. 1216), Akhbar al-Duwwal al-Munqati‘a

• Ibn Hammad (1153-1230), Akhbar muluuk Bani ‘Ubayd wa siratuhum

• Ibn Muyassar (1231-78), Ta’rikh Misr

• Ibn Khallikan (d. 1211-1282), Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān (Biographical Dictionary)

• Ata Malik al-Juwayni (1226-1283), Tarikh-i Jahan-Gushah

• Rashid al-Din (1247-1318), Jami‘ al-Tarawikh

• Ibn al-Dawadari (d. 1313), Kanz al-Durar wa jam‘i al-Ghurar

• Al-Marrakushi, (fl. early 14th century), al-Bayan al-Mughrib

• Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Muqaddimah

• Ibn ‘Inaba (d. 1424), Umdat al-Talib

• Al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), Al-Itti’az al-hunafa bi-akhbar al-a’imma al-Fatimiyyin al-khulafa

• Idris Imad al-Din (d. 1468), ‘Uyun al-Akhbar; Zahr al-Ma‘ani

(See Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis: Their History and Doctrines, 565-599; Paul Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources, 93-169 for discussion of coins, buildings, inscriptions, letters, eyewitness accounts, and histories about the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs)

14. Imam Ma‘add Abu Tamim al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah (953-975)

We are the everlasting words of God and His perfect names, His radiant lights, His luminous signs, His evident lamps, His created wonders, His dazzling signs and His effective decrees. No matter passes us by and no age is devoid of us.

Imam al-Mu‘izz li-Din Allah,

(Letter to the Qaramita, tr. S. Jiwa, Towards a Shi‘i Mediterranean Empire, 172)